This feature is a collection of summaries from a few of the speakers at HPE LIVE 2015, which took place at the National Conference Centre in Birmingham on 13 October

Annabel De Coster

Commissioning Editor, HPE

Medicines optimisation: helping your patients reach their respiratory treatment goals

Toby Capstick

Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust, UK

This feature is a collection of summaries from a few of the speakers at HPE LIVE 2015, which took place at the National Conference Centre in Birmingham on 13 October

Annabel De Coster

Commissioning Editor, HPE

Medicines optimisation: helping your patients reach their respiratory treatment goals

Toby Capstick

Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust, UK

Inhaled medicines are some of the most commonly prescribed medicines in primary care in England, and accounted for six of the top seven drugs in terms of overall expenditure in primary care in 2014. However, despite widespread prescribing for asthma and COPD, there remains a significant burden of disease in the UK. There are 5.4 million people in the UK with asthma, and in 2011, there were 1167 deaths, of which 90% were thought to be preventable. It has also been estimated that there are three million people with COPD in the UK and the number of deaths each year are rising. While the reasons for this are varied, there is evidence of sub-optimal prescribing in asthma and COPD and over-prescribing of inhaled corticosteroids, poor adherence to prescribed treatment, and an inability of patients to use inhaler devices correctly.

In the past few years, there has been a significant increase in the number of licensed inhaled drugs for the management of asthma and COPD, which create a number of opportunities for pharmacists to optimise patients’ medicines and improve respiratory management. Benefits for patients may be achieved through increased awareness of evidence-based treatment guidelines and the use of newer inhaler devices that may more closely meet the criteria of the ideal inhaler in terms of dose delivery, being easier for patients to use and for patients to know that they have received the intended dose.

In order to best achieve value for money with medicines use, it is important to regularly demonstrate and check inhaler technique, assess adherence, and to use the most cost-effective medicines acceptable to each patient.

Key points

- Despite widespread prescribing of inhaled medicines, there continues to be a significant burden of disease in both asthma and COPD.

- Poor prescribing in asthma and COPD, and non-adherence may contribute to poor outcomes.

- The recent substantial increase in the number of available drugs and inhaler devices creates opportunities for pharmacists to optimise asthma and COPD management.

- Correcting and maintaining good inhaler technique is a key component of asthma and COPD management.

- The use of cost-effective treatment options at each stage of disease is important to ensure that the NHS achieves value for money.

Refer-to-Pharmacy: the first fully integrated, hospital-to-community-pharmacy e-referral system

Alistair Gray

Clinical Services Lead Pharmacist, East Lancashire Hospitals NHS Trust

Refer-to Pharmacy is the only integrated hospital to community pharmacy referral system. It has been conceived and designed to make it quick and easy to operate on hospital wards and in community pharmacies. This makes it feasible to refer high numbers of patients on a daily basis, improving transfer of care, medicines safety and medicines adherence, reducing medicines waste, reducing unscheduled hospital attendances.

It works by hospital pharmacists and technicians just doing their regular job. They naturally identify patients, anytime from admission to discharge, who are eligible for referral to their community pharmacist either for a consultation (new medicine service, medicines use review) or for information, for example, changes to prescriptions of care home residents or blister pack users. An initial message is additionally sent for blister pack and care home patients informing a pharmacy their patient is in hospital and to pause dispensing until notified of discharge.

Patients are engaged with at their bedside where they are shown a film explaining the benefits they can expect by referral to their community pharmacist (watch it on www.elht.nhs.uk/refer).

It is possible to make a referral without actually typing anything as a single identifier can be scanned (or typed) in to the application obtaining instant patient demographics. A reason for referral is selected, and then Find-a-Pharmacy uses either a list or interactive map to identify the patient’s community pharmacy.

A referral is automatically released only when the patient is discharged and their discharge letter is completed; if there’s no letter the referrer is informed so action can be taken.

Community pharmacists receive a prompt to log in to accept a referral, only finding out details of the patient once they securely sign in. The information is held on a secure N3 network and is encrypted. Upon acceptance, they can view the entire discharge summary with diagnostic information, current drug history and changes to medicines. They may then update their patient’s medication record or contact them to arrange a consultation. Referrals are closed and archived by capturing an outcome measure from a dropdown menu.

The system is designed for spread and is adaptable to other health economies. Additional referral routes can be added, for example, home visit for domiciliary pharmacy teams.

Refer-to-Pharmacy is a medicines optimisation tool that lets hospital and community pharmacists work together to help people get the best from their medicines and stay healthy at home. For more information, contact [email protected].

Key points

- Transfer of care

- Electronic referral

- New Medicine Service

- Medicines Use Review

- Medicines Optimisation

Delivering a system-wide coordinated care model to support patients in the management of medicines to retain independence in their own home

Michelle Hoad

Principal Pharmacist for Community Health Services & LIMOS, Lewisham & Greenwich NHS Trust

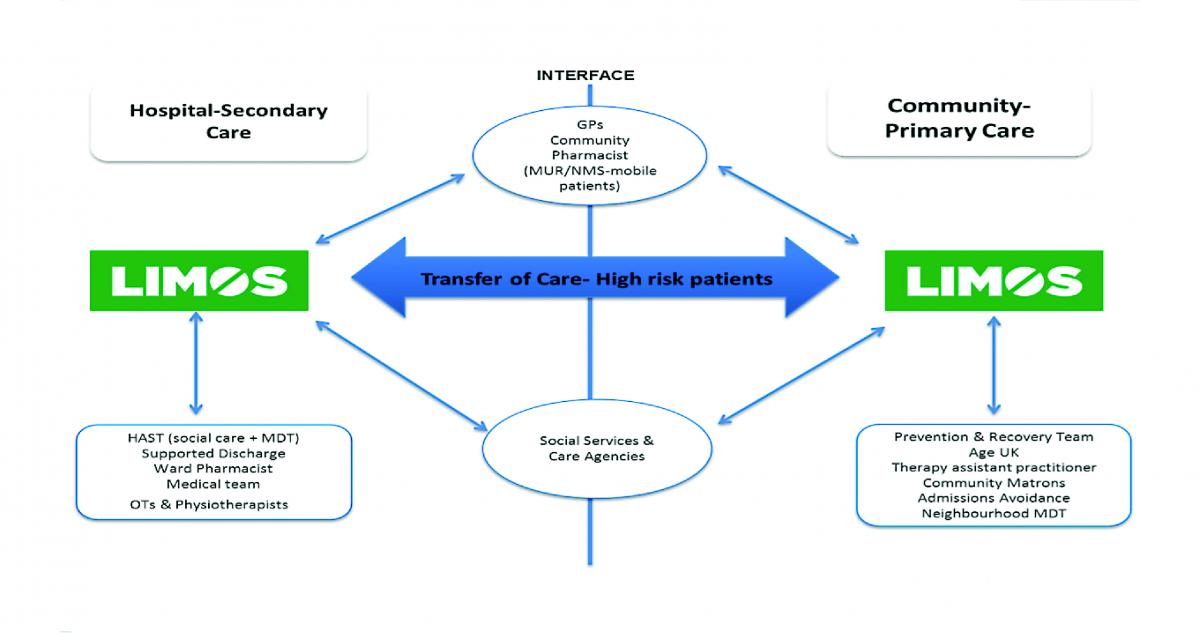

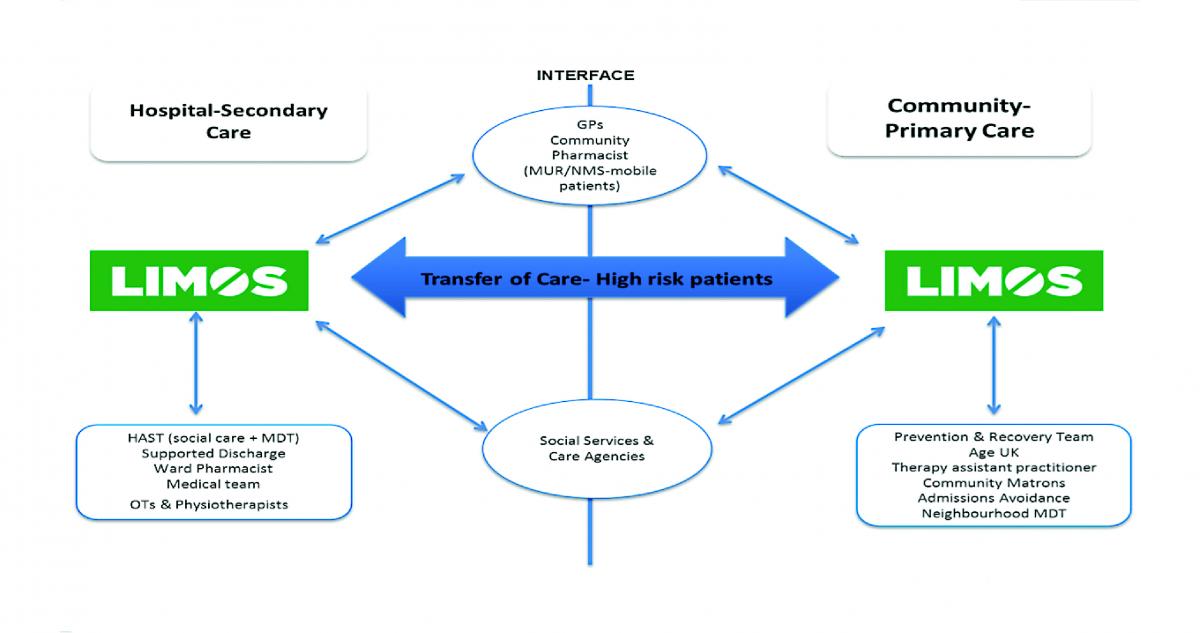

In order to support patients to manage their medicines and retain independence, an integrated model of care is needed that no single sector or profession can deliver in isolation. The Lewisham Integrated Medicines Optimisation Service (LIMOS) operates not only across the traditional primary and secondary care interface but also across professional, health and social care boundaries.

LIMOS consists of a team of four specialist pharmacists and two pharmacy technicians who rotate geographically to work in both primary and secondary care settings, enabling them to form effective working relationships with the wide range of individuals with whom communication is essential to coordinate the integrated package of care around medicines use. An overview of the LIMOS model is shown in Figure 1.

LIMOS aims to support patients identified as having or being at high risk of medicine-related problems, which can include: those who are housebound; those with complex medication regimes; those with medicines-related hospital admission, requiring a social care package for medicines support; or where a request for a compliance aid has been made.

LIMOS receives referrals from health and social care colleagues, including GPs, hospital doctors, district nurses, specialist nurses, hospital and community pharmacists, social workers and domiciliary care agency staff. LIMOS undertakes a patient consultation, either in the home or in the hospital, to assess and review all medicine issues, discussing access, adherence, day-to-day management and clinical aspects.

An integrated and deliverable pharmaceutical care plan is developed, agreed and communicated with the patient and all those involved in their care. A range of interventions can be introduced including: rationalisation of medication regimes, information provision, liaison with community pharmacy to implement adjustments to support self-care, for example, large print labels, medication reminder charts and monitored dosage systems, and setting up of formal or informal carer administration of medication. Regular structured follow-up is provided, either via telephone or further home visit, to ensure the interventions introduced continue to meet the individual’s needs.

In the first year of the service, 947 interventions were made in 468 patients reviewed, supported and discharged by LIMOS (excludes patients remaining on the active caseload) which resulted in an estimated reduction of 166 A&E attendances and an associated 29.5 hospital admissions. Alongside this, 238 unnecessary medicines were stopped, 181 unnecessary social care visits for medicines administration were prevented and 70 unnecessary compliance aids were avoided; all combining to give an estimated cost saving of £658,000.

Figure 1: Overview of the Lewisham Integrated Medicines Optimisation Service (LIMOS)

Key points

- Lewisham Integrated Medicines Optimisation Service (LIMOS): an integrated model of care operating across primary and secondary care interface and health and social care boundaries.

- Support patients with or at high risk of medicines-related problems referred by range of health and social care professionals.

- Patient consultation to assess medicines issues: access, adherence, day-to-day management and clinical aspects.

- Developing and agreeing an integrated and deliverable pharmaceutical care plan which is communicated with the patient and all those involved in their care, with structured follow-up 12 month outcome: estimated reduction of 166 A&E attendances and 29.5 associated hospital admissions.

Red, black and blue: immunoglobulin demand management

Aarn Huissoon

West Midlands Immunodeficiency Centre, Birmingham Heartlands Hospital, UK

The Department of Health’s immunoglobulin (Ig) demand management programme was borne out of a series of crises in Ig supply and the sense that Ig was being used for an increasing number of conditions, sometimes with little evidence to support this. The purpose was therefore to provide guidance on when Ig treatment was indicated, and to prioritise indications for Ig use so that rationing decisions could be made in the event of a shortage of product.

The tools for implementation were:(1) published clinical guidelines; (2) a database of all Ig used; and (3), local immunoglobulin assessment panels.

The clinical guidelines were constructed by a panel of experts from relevant specialties. They were first published in 2008, with an update in 2011 and a further update is expected soon. The guideline lists all conditions commonly treated with IVIg, grouped by specialty. It provides summary guidance on patient selection, treatment recommendations and outcomes to be recorded. There is also an indication of priority, given by colour: ‘red’ indications have high priority with conditions listed as ‘blue’ being lower. In addition it lists a number of conditions where Ig is known not to work (‘black’), and some where more evidence is needed (‘grey’).

Ig assessment panels are required to review each new application for Ig use. Some indications (for example, primary immunodeficiency, ITP) are automatically approved. Others requests need to be considered by the panel and either approved or rejected (usually after discussion with the clinician involved). In times of plenty, rejections are usually because of inadequate evidence that the patient fulfils criteria for treatment. The approval process also gives the panel the opportunity to reject applications in times of Ig supply shortage, when alternative treatments may be available (for example, steroids or plasmapheresis).

Each approved application for Ig is entered onto the DH Ig database. For each patient, each dose is also entered, with batch numbers and recording of adverse events. Finally, recording of treatment outcomes is required for the majority of indications for Ig. These outcomes are notoriously hard to obtain from the requesting clinicians!

The centralised process also gives opportunities for a national approach to events such as individual product withdrawals or recalls, identification of rare or batch-related adverse events, or even management of blood product tracing in the event of the discovery of a transmissible agent (for example, variant Creutzfeld-Jacob Disease). There is also the possibility of answering research questions from the large number of treatment episodes and outcomes recorded.

Why integrating ward-based pharmacy technicians improves patient care

Anthony Sinclair

Chief Pharmacist, Birmingham Children’s Hospital NHS Foundation Trust

Pharmacy technicians were introduced onto a busy oncology ward, as members of the nursing not pharmacy ward team. technicians were partnered with nurses for the preparation and administration of, intravenous (IV) medicines. The technicians fulfilled the role of one of the two checkers mandated for high-risk drug administration in paediatrics. Technicians in addition were able to undertake the preparation of IV medicines.

The pharmacy technician and nurse team were supported with a specially designed checking protocol, inspired by the World Health Organization (WHO) Safer Surgery checklist, and based on the five rights of medicines administration that in addition had a calculation aide on the reverse.

The pharmacy technicians received additional training from nurse trainers that included aseptic non touch technique and the use of administration pumps. Professional boundaries were established for the partnered process between the technical role of the pharmacy technician involved in preparing or checking the medication and the additional responsibilities of the nurse in making clinical decisions based on patient assessments made prior to during and following administration of intravenous medicines Nurse trainers also acted as mentors. A senior medicines management nurse based within the pharmacy department oversaw the project. This was a nurse led project.

The technician–nurse team was a genuine multidisciplinary skill mix team. The technicians brought a protocol driven proactive medicine approach to safety to the partnership, whilst the nurse added the necessary clinical patient facing knowledge and skills elements.

Data were collected throughout the project and arguably for the first time gave a snapshot view of what actually occurs during medicines administration as opposed to collecting data through overt or concealed observation. In addition two surveys were carried out to assess the views of the nursing team to the project. The first survey was an unstructured set of interviews of a cohort of the nursing team and the second was by means of structured questions using a questionnaire.

Initial project data have shown that this partnership has had a direct and measurable impact on reducing medicine related incidents and therefore on improving patient safety. In addition by virtue of the fact that a technician has joined the team, nursing time to care has been generated.

This project marks a new pathway for pharmacy technician professional development and gives a competency set that has been derived independently of pharmacist colleagues.

Key points

- A truly multi-professional skill mix approach to patient care.

- Releasing nursing time to care.

- Improving patient safety by introducing a proactive protocol approach to medicines administration, capturing errors that previously escaped capture.

- Improved medicines management on wards for example medicine storage and stock levels.

- Impact on risk management of medicines – improved calculation and IV flow rate management.

Transformation of care: implications for pharmacy services

David Terry

Aston University

Elizabeth Hughes

Matt Aiello

HEWM

At present there are concerns about maintaining appropriate clinical staff levels in emergency departments in England. Pharmacists are experts in medicines optimisation. However, they may have further untapped potential and may be able to extend their clinical role beyond that of current clinical pharmacist roles. The aim was to explore potential clinical management roles that hospital pharmacists could undertake within emergency departments after further training. The study was led and commissioned by HEWM.

Methods

Pharmacist independent prescribers (one from each of two sites) were asked to identify patient attendance at their ED, record anonymised details of cases and categorise each into one of four possible categories:

- CP, Community Pharmacist, cases that could be managed by a community pharmacist in a community pharmacy.

- IP cases that could be managed in ED by a hospital pharmacist with independent prescriber status.

- PT, Independent Prescriber Pharmacist with additional training, cases which could be managed in ED by a hospital pharmacist independent prescriber with additional clinical training.

- MT, Medical Team – unsuitable for pharmacist management.

Blinded secondary categorisations of cases were conducted by two community pharmacists and two ED medical consultants. Cases were classified into eighteen clinical groupings, and an Impact Index was calculated for each using the formula: I(i) = workload (%) x Pharmacist management (%).

Results

A total of 782 patient admissions were recorded. Of these, 3.2% of the cases were considered suitable for pharmacist management outside the hospital in community pharmacy and 5.1% were considered suitable for a hospital pharmacist independent prescriber. An additional 39.9% were considered suitable for a hospital based independent prescribing pharmacist management after further advanced clinical practice training (proposed length of training was one year). Impact index was highest for ED attendees classed as orthopaedic (19.8) and general medicine (12.8). Impact Index is a measure of the potential for pharmacists to impact positively on the workload of EDs.

Conclusions

This study confirms that there is moderate scope for pharmacists with existing training to manage patients attending ED, approximating to 1 in 12 patients. A review of cases attending ED undertaken by a multi-professional group consisting of pharmacists and medical staff, suggests that there is potential for pharmacists to manage up to 48.2% of ED attendees, provided they received further structured training of no more than 12 months duration. Training in clinical specialities with a high impact index may be most suitable for pharmacists with clinical roles within emergency medicine.

Key points

- There are national concerns about maintaining clinical staff in emergency departments.

- Pharmacists may be able to extend their clinical skills beyond being independent prescribers.

- A study of ED attendees in the WM suggests additional training for pharmacists may support multi-professional management of these patients.

- Pharmacists with existing training have potential to manage around 8% of cases, but this rises to approximately 48% if further suitable training could be undertaken.

- Advanced practice pharmacists may be most useful in supporting general medicine and orthopaedic patients (with minor trauma).