Pharmacists play an important role in clinical care and the manner in which such care is delivered is evolving. A way of capturing pharmacists’ contribution to patient care when not on the ward and which might have service implications, is presented

Pharmacists play an important role in clinical care and the manner in which such care is delivered is evolving. A way of capturing pharmacists’ contribution to patient care when not on the ward and which might have service implications, is presented

Kazeem Olalekan

Specialist Pharmacist Paediatrics

David Young

Clinical Pharmacist

Julia Baker

Clinical Pharmacist

Emma Dracass

Lead Pharmacist Acute Medicine

Christina Nurmahi

Lead Pharmacist Woman & Newborn

Lindsay Steel

Principal Technician Medicines Management

Michelle Cerrato

Lead Pharmacist Cardiology

University Hospitals Southampton NHS FT

Sharron Gordon

Consultant Pharmacist Anticoagulation

Hampshire Hospitals NHS FT

Email: [email protected]

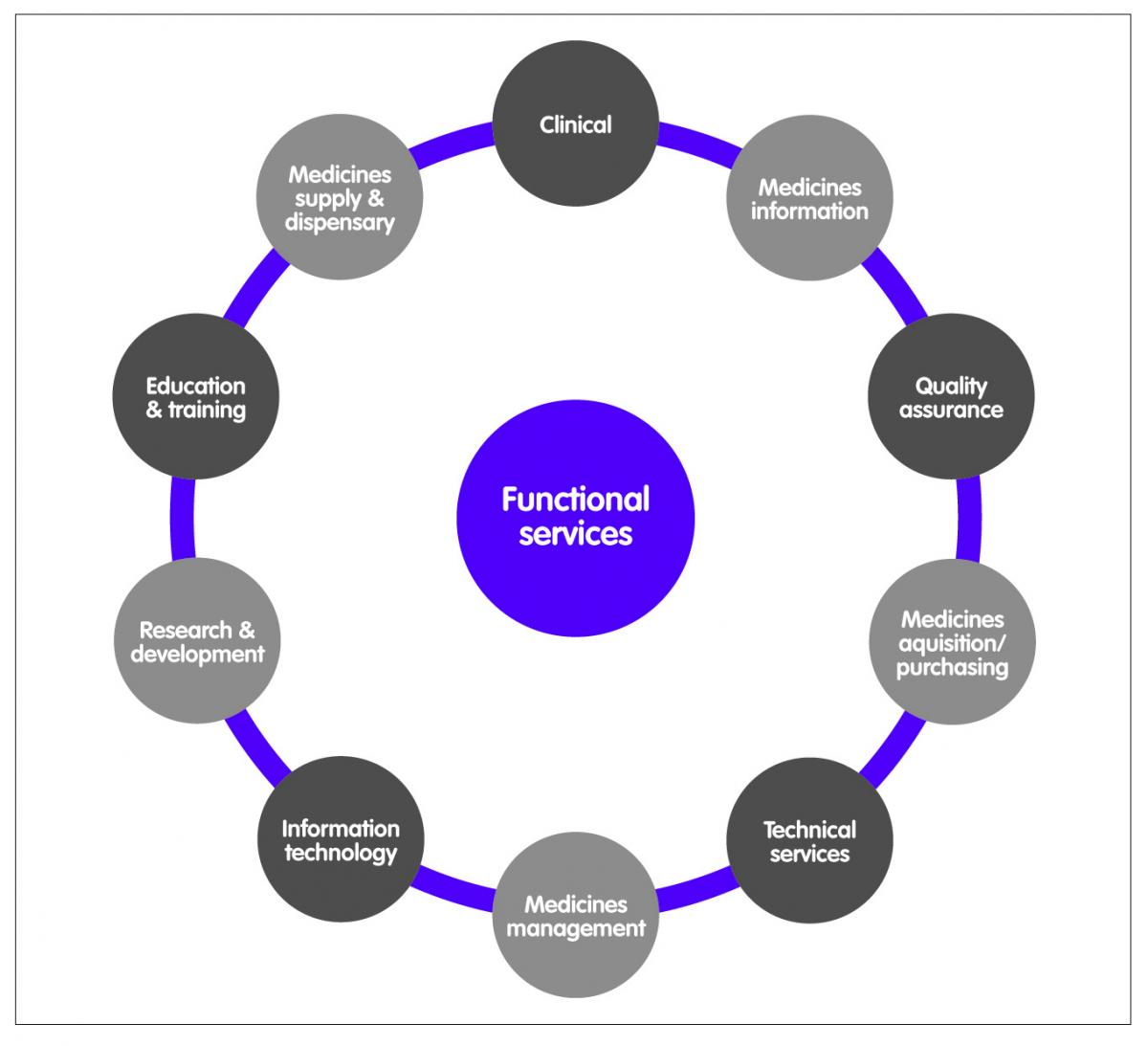

The evolution of hospital pharmacy practice in the UK has resulted in what may be perceived as a structural disjoint. Up until the mid 1960s, hospital pharmacists engaged mostly in traditional pharmaceutical activities such as manufacturing and dispensing; but the increasing range and sophistication of medicines available, awareness of medication errors and the widespread use of ward-based prescription charts brought pharmacists out of the dispensary and onto the wards in increasing numbers.1 The pace of adoption of the clinical pharmacist role varied across UK hospitals whereby some hospitals had ward-based pharmacists who practice as key members of the clinical team, whilst others had pharmacists who may visit the ward on an irregular basis to review medication charts and promote formulary compliance.2 Over time, hospital pharmacist roles have divided along functional service lines (Figure 1).

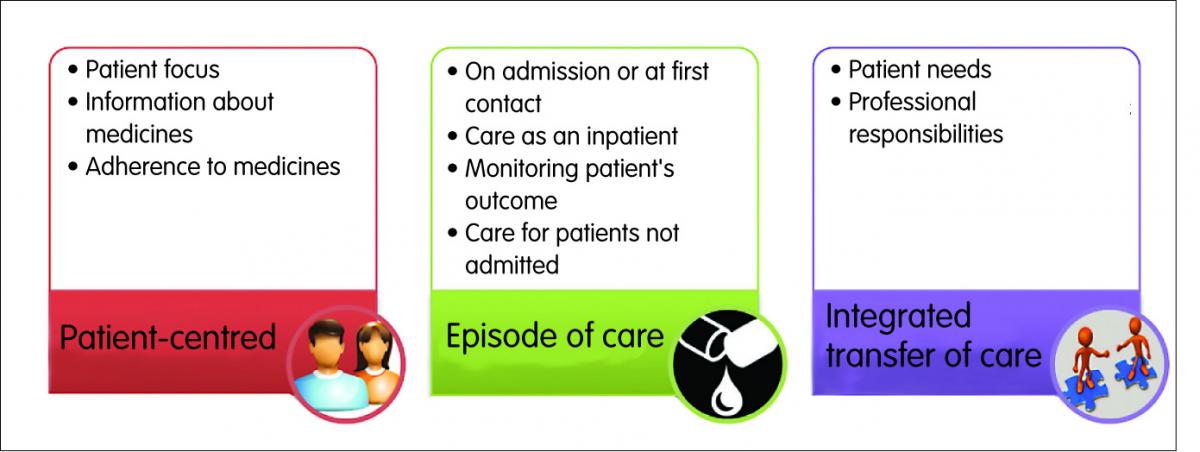

Figure 1: Hospital pharmacist roles

The division across service lines may be unhelpful in achieving a paradigm shift from a drug-centred orientation to a patient-centred orientation. Clinical pharmacy practice, due in part to its evolution, offers a blueprint for a patient-centred orientation whereby patients (and/or carers) are supported in their decision-making about medicines. Clinical pharmacy has been defined as the area of pharmacy concerned with the science and practice of rational medication use; or more elaborately, as a health science discipline in which pharmacists provide patient care that optimises medication therapy and promotes health, wellness, and disease prevention.3 Clinical pharmacy embraces the concept of pharmaceutical care4 and medicines management. All hospital pharmacists therefore engage in clinical pharmacy practice. The level and complexity of that practice will vary depending on role and experience.

Structural disjoint

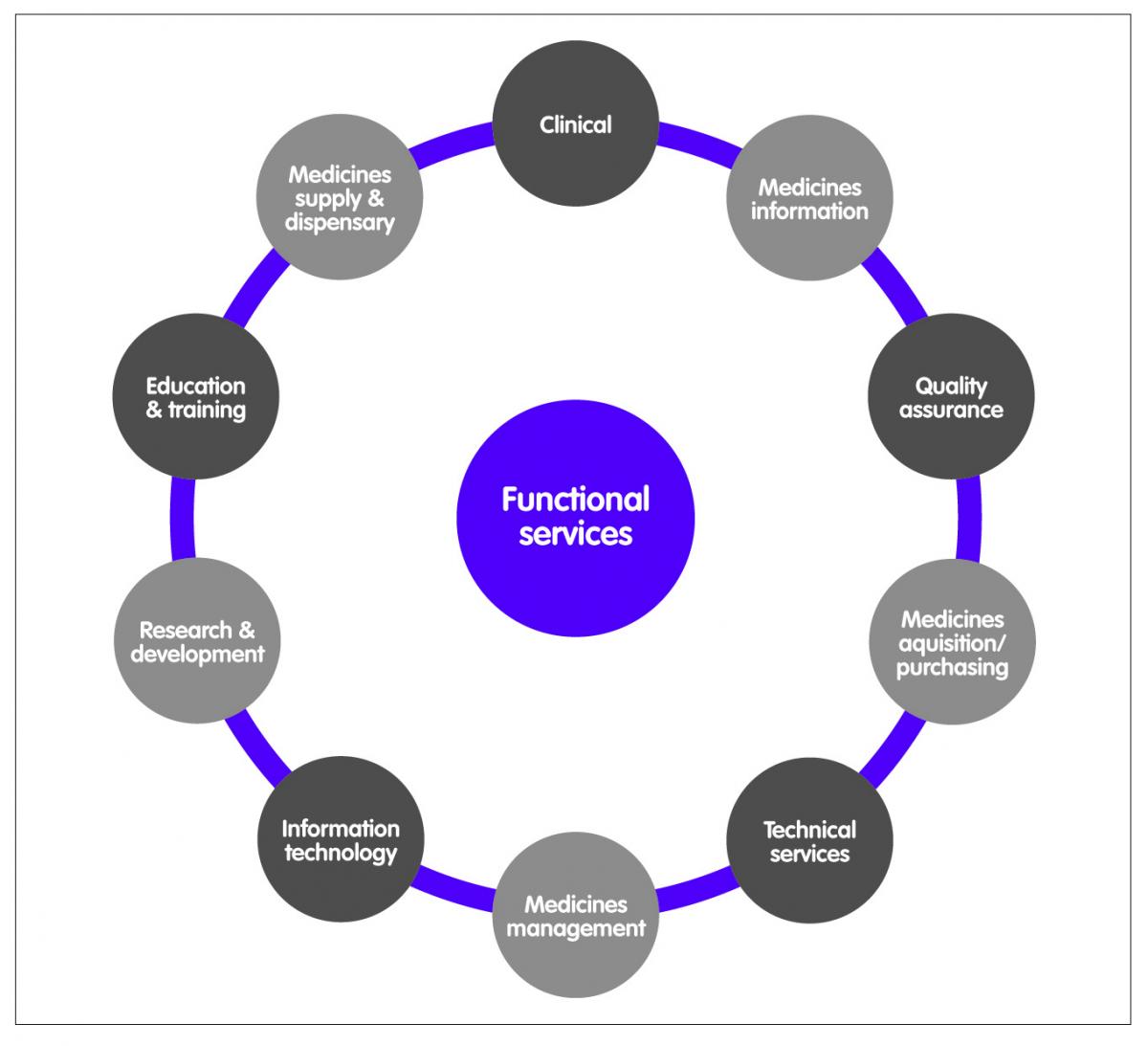

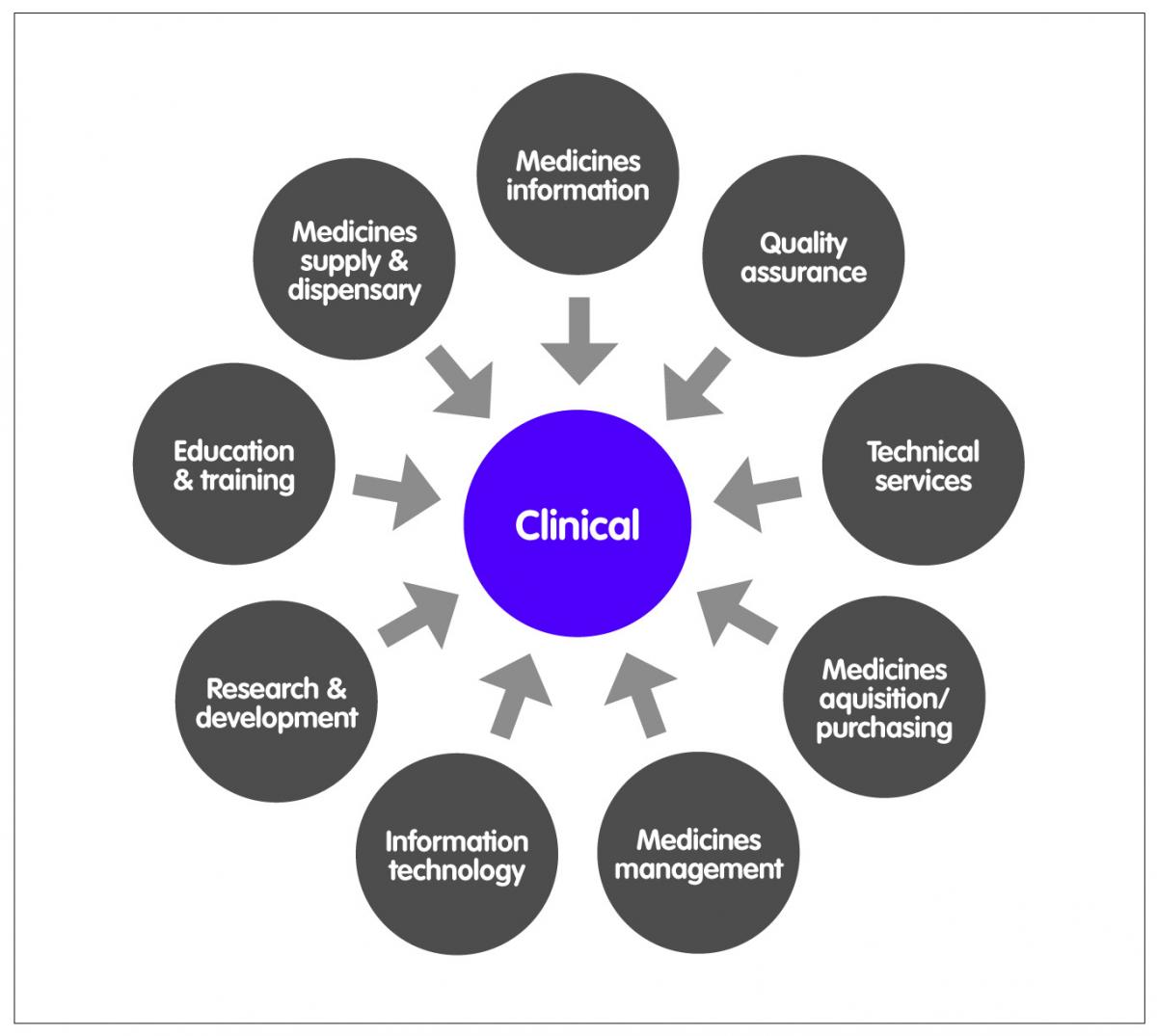

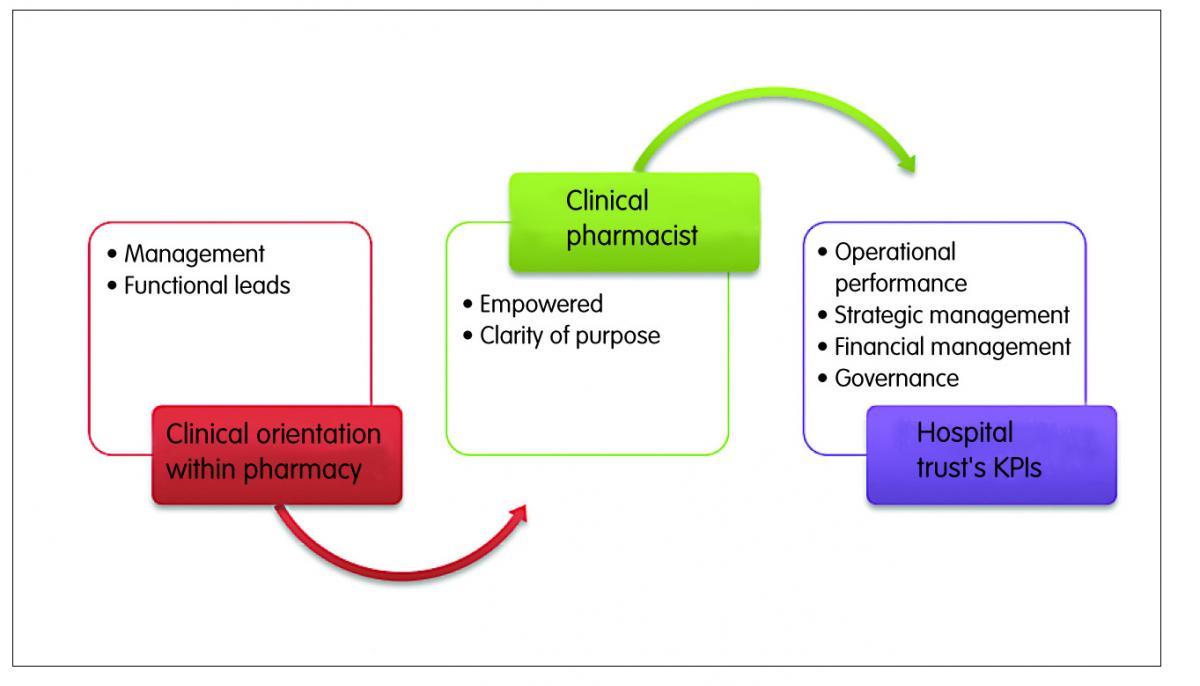

A structural disjoint arises when all the service roles have no common element and may result in the ‘silo effect’: a tendency for groups to focus largely on their own functional processes or roles. A paradigm shift will require all hospital pharmacists to see their roles as either clinical or supporting the clinical role. Figure 2 illustrates this shift in structure.

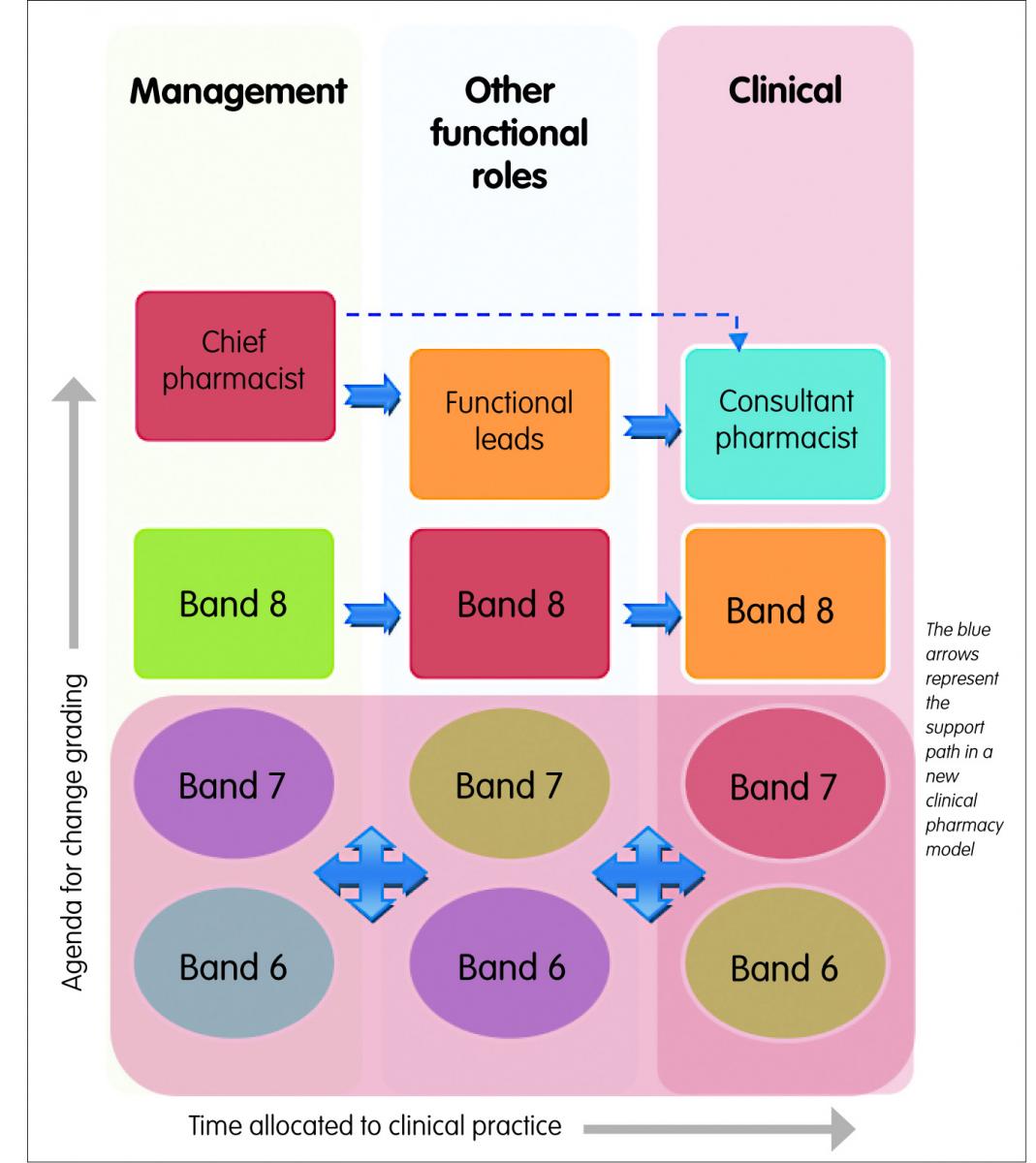

The clinical role is a patient facing role and is the gateway to multidisciplinary practice across the hospital trust and the wider public. When the clinical pharmacists ask the question of how to effectively discharge their clinical duties, all the other roles should be asking how they can support the clinical pharmacist in discharging these duties. This shift demands a fundamental review of each role (including that of the clinical pharmacist) and divesting from duties that do not support the clinical role. This proposal is not novel5 but its adoption has been varied across hospital trusts.6 Figure 3 maps the current hospital pharmacist career paths. If the consultant pharmacist represents the pinnacle of clinical practice with four key functions: (1) expert practice (maximum 50%); (2) research, evaluation and service development; (3) education, mentoring and overview of practice; and (4) professional leadership; then it is surprising that a 2012 survey identified only 41 consultant posts in England, with no posts in Scotland, Northern Ireland or Wales.7 Of these, 68% work in acute teaching hospitals, 12% in acute non-teaching hospitals, 5% in mental health, 7% in primary care and 5% in specialist trusts. With 156 acute trusts, 56 mental health trusts, 18 community trusts and 10 ambulance trusts in the English NHS,8 this represents only 17% appointment rate. It is difficult to see how a shift towards a clinical focus can happen with such dearth of clinical pharmacy leadership.

Figure 2: Clinical pharmacy model

Figure 3: Hospital pharmacist career paths

The clinical role

At the most fundamental level, the clinical role must facilitate the effective delivery of domain one of the professional standards for hospital pharmacy services: patient experience9 (Figure 4).

The developments of supplementary and independent prescribing roles are enablers for a multidisciplinary approach to safe and effective use of medicines. Researchers have shown the benefits of this approach: (1) A study looking at a collaborative approach to pharmaceutical care from admission to discharge reported a reduced prevalence per patient of error at admission and discharge from adult inpatient care;10 (2) On-ward participation of a hospital pharmacist in an intensive care setting has been shown to reduce prescribing errors and related patient harm;11 and (3) Pharmacists attending consultant-led ward rounds, in addition to undertaking ward pharmacist visits make significantly more interventions per patient than those made by pharmacists undertaking a ward pharmacist visit alone.12

Figure 4: Fundamental clinical roles

Figure 5: Potential impact of structural shift

The increasing use of technology, like electronic prescribing systems in hospitals, has impacted on how the clinical role is discharged. Access to drug charts and clinical results outside of the clinical areas (or wards) has resulted in some clinical roles being discharged off-ward. A number of methods have been described for capturing intervention data made by clinical pharmacists on wards.13,14 The methods essentially require the pharmacist to collect the intervention data over a specific time frame using standardised forms. As the role of the clinical pharmacist expands to include development of safe systems within clinical areas and supporting financial governance, an increasing number of duties will be discharged outside of the ward or clinical setting. A robust way of capturing hospital pharmacist contribution to patient care outside of the clinical or ward setting is yet to be fully described. Our aim was to develop and pilot a methodology for capturing clinical pharmacy ‘off-ward’ activities.

Our approach

Our approach was based on the precept that a structural shift from a functional (possibly inward) outlook to a more clinical (possibly outward) outlook within pharmacy empowers the clinical pharmacists to align their functions and strategies to that of the hospital trust, within which they operate (Figure 5). Structural empowerment is a positive predictor of organisational commitment, loyalty, performance and retention in hospital pharmacy.15,16 Such empowerment may also help to allay anxieties around a benchmarking exercise, which hospital pharmacy departments have sometimes struggled with.17

Through a series of meetings, the project team set out to:

- Clarify and agree terminologies

- Design an activity capturing model

- Agree pilot data collection week(s)

- Collect data

- Analyse and present results

Terminology

On the basis of feedback from senior members of the department, we agreed the following set of criteria:

(i) ‘Off-ward’ activities start from the point of leaving the ward and end at point of arrival on the ward.

(ii) It was not necessary to capture time-to-travel to and from wards.

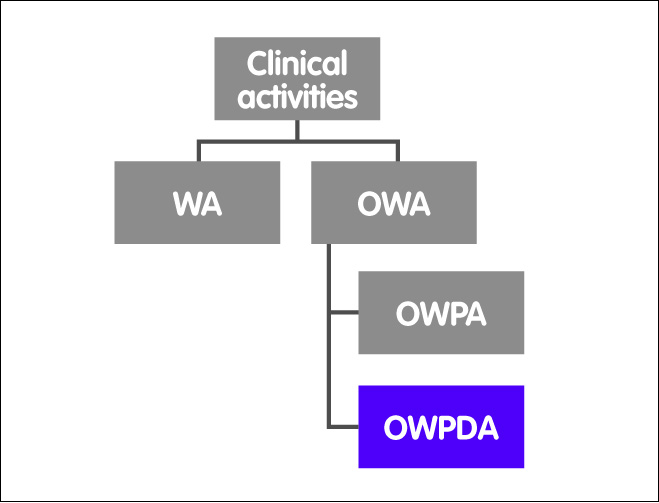

(iii) Clinical activities (CA) include practices based on observation and treatment of patients. That includes the sum of everything that the clinical pharmacists do.

(iv) Ward Activities (WA): all clinical activities that take place on the wards or clinics.

(v) ‘Off-ward Activities’ (OWA): all clinical activities that take place outside the wards or clinics.

(vi) ‘Off-ward Patients Activities’ (OWPA): All clinical activities primarily involving patients.

(vii) ‘Off-ward Trust Policy Development Activities’ (OWPDA): all clinical activities with secondary involvement of patients. This may include development of policies and procedures, medicines finance, learning, teaching and other activities that contribute to the Trust’s strategic vision of operational performance, strategic management, financial management and quality, and safety development.

Figure 6 is a representation of these terminologies.

The consensus was that the focus of this work should be “off-ward trust policy development activities” (OWPDA) since the other activities are captured using established methodologies.

Figure 6: Relationship between terminologies

Design of model

We designed a data capturing form with activities aligned to the trust’s key performance indicators (KPIs).

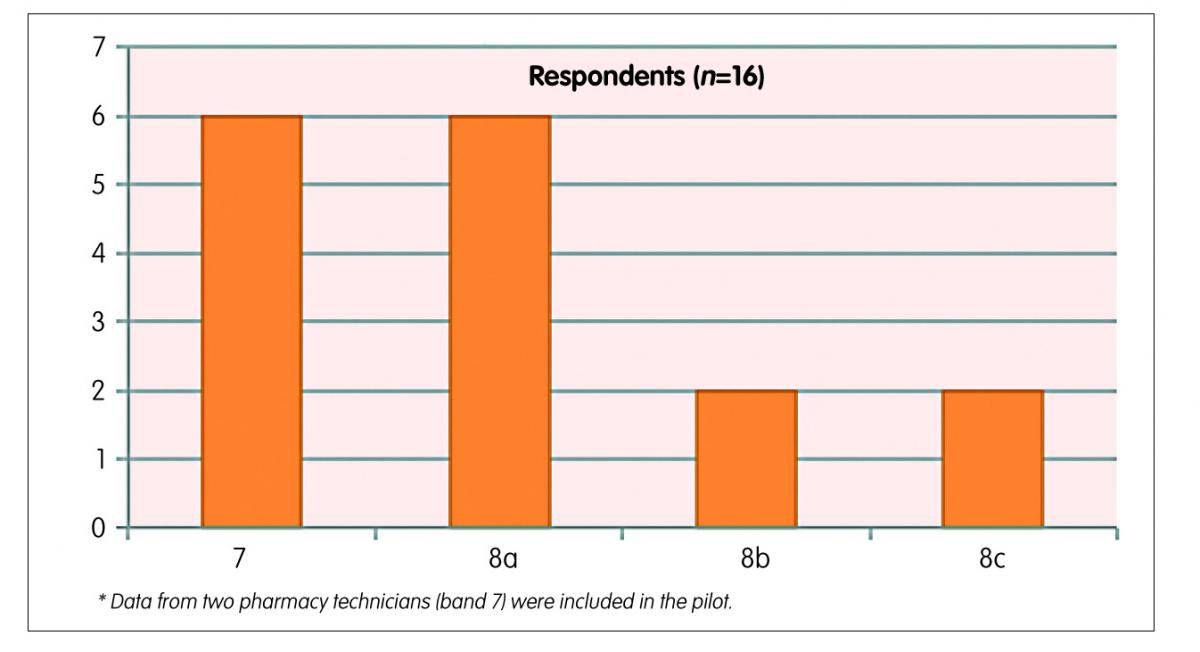

In line with other intervention capturing models, clinical pharmacists (and pharmacy technicians) collected the activity data over a two-week period.

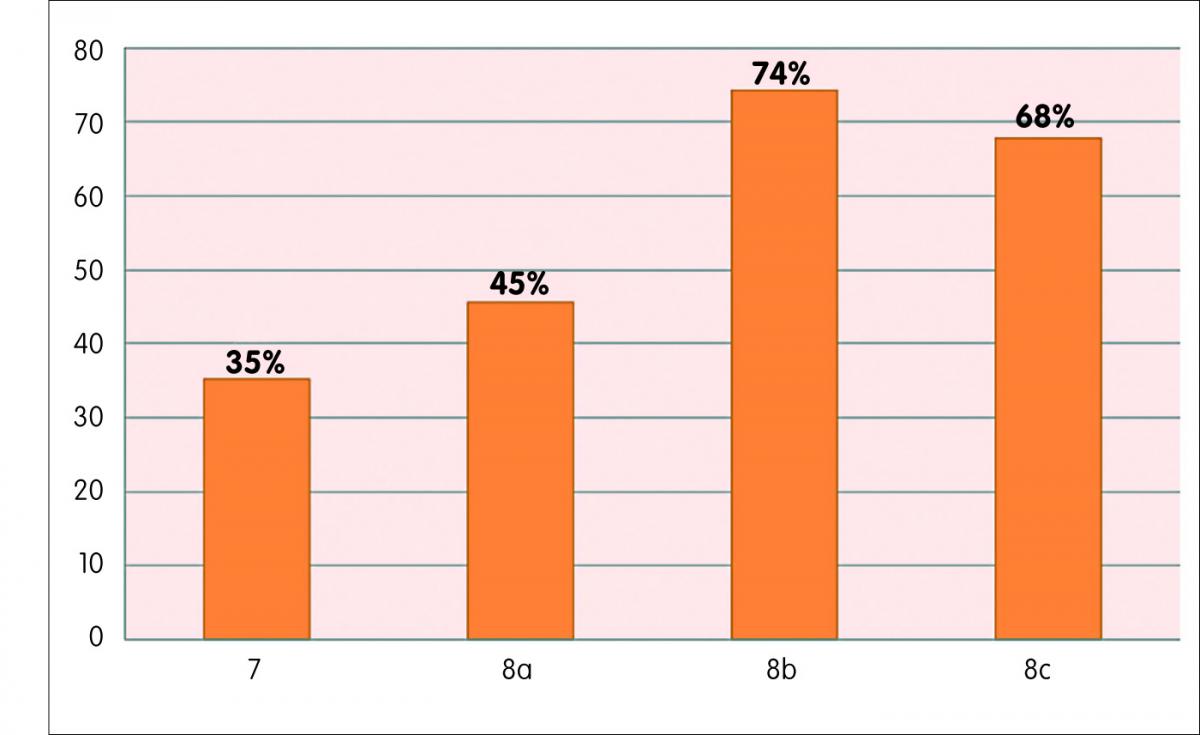

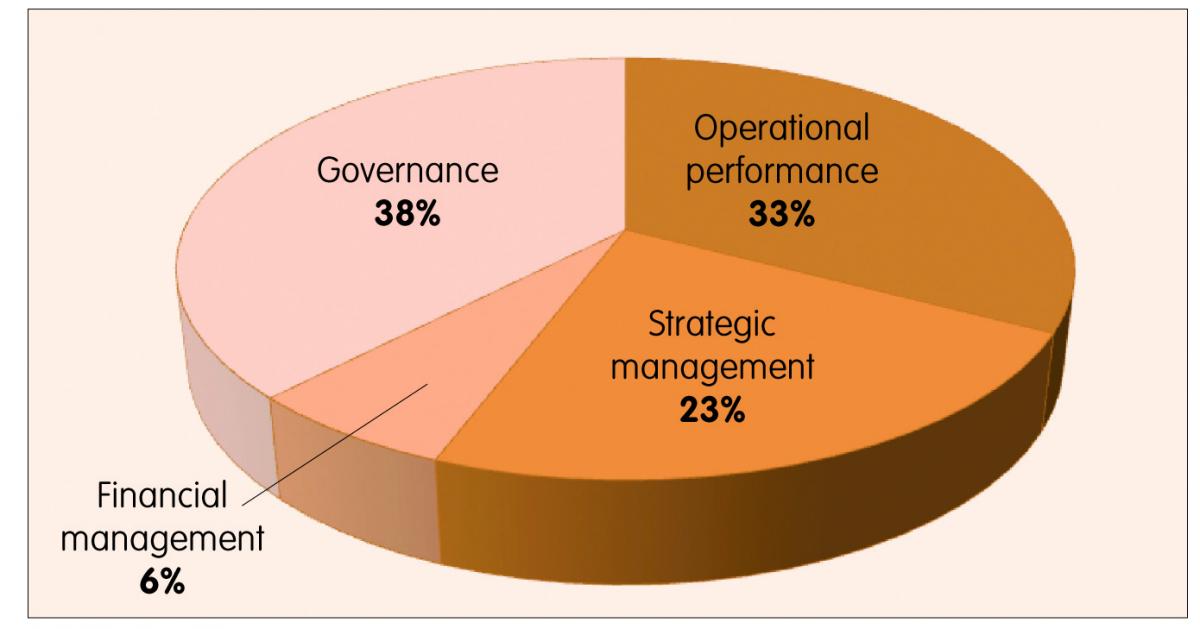

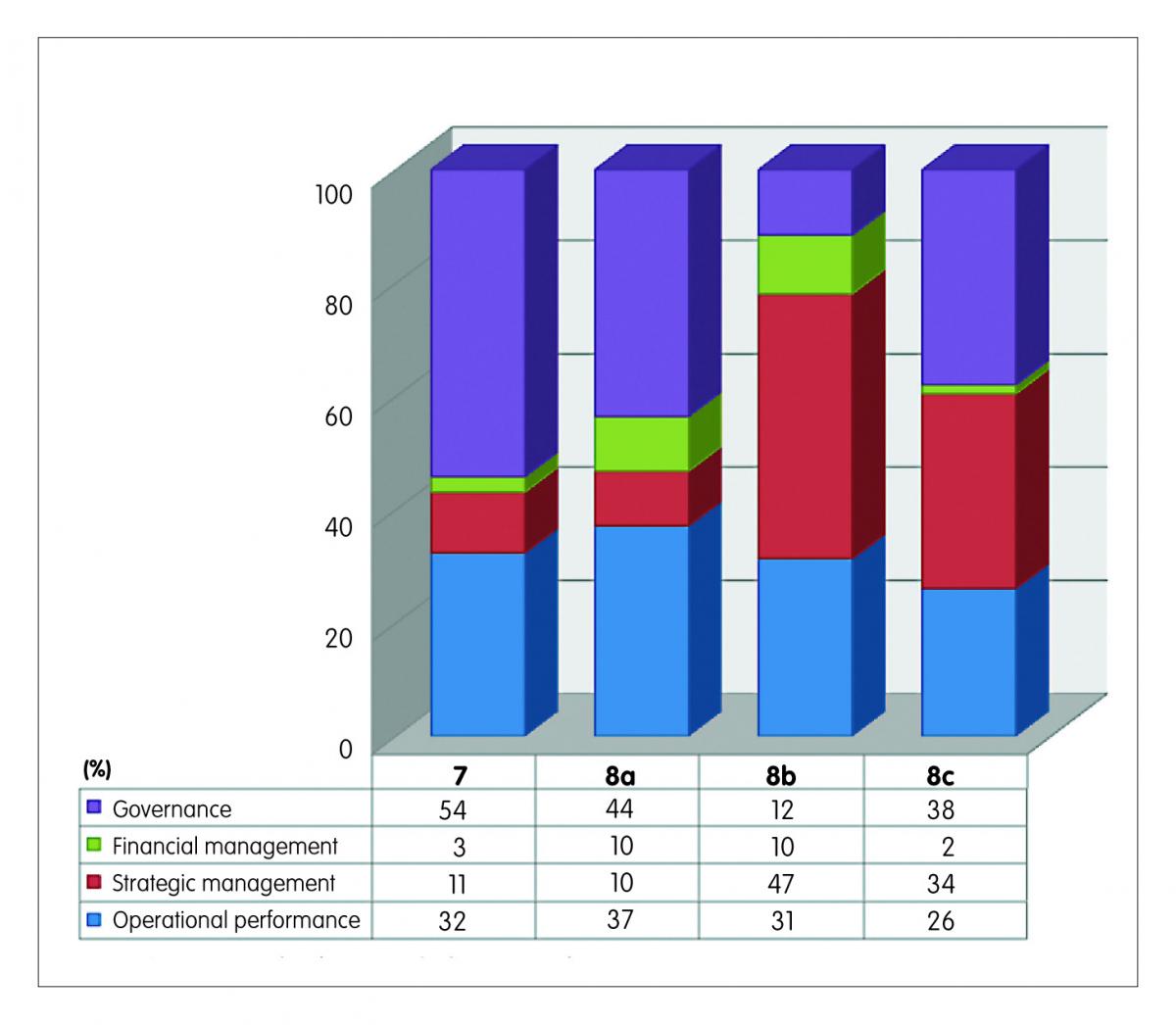

Over the two-week pilot period, the respondents spent a total of 434 hours on ‘off-ward’ activities (equivalent of 45% of hours worked in the study period) (Figures 7–10).

In 11% of cases respondents have either failed to report a category or unsure of how to categorise activity.

– Of the 11%, the task description provided by respondent was sufficiently robust to accurately categorise event in 7% of cases.

– In 4% of cases where task description of activity was insufficient, the hours were distributed evenly to reduce bias.

Figure 7: Results of the pilot

Figure 8: Proportion of time worked spent on ‘off-ward’ activities

Figure 9: Breakdown of proportion of time spent ‘off-ward’ over the study period

Figure 10: Proportion of time worked spent on ‘off-ward’ activities

Box A: Some activities reported

Examples of operational performance activities reported

Band 7:

- Attending to emails

- Preparing handover information

Band 8a:

- Attending to emails

- Drop off BNF to theatre & bring back excess stock to store from theatre

Band 8b:

- Attending to emails

- Cystic fibrosis (CF) meeting

Band 8c:

- Attending to emails

- Meeting planning

Examples of strategic management activities reported

Band 7:

- Problem solving

- Strategic performance management

Band 8a:

- Amendment to patient specific information sheet in readiness for discussion

- Library research around new HIV service strategy

Band 8b:

- Cancer Network – presentation on e-prescribing

- Length of stay meeting

Band 8c:

- International peer support/discussion

- Central Southern Critical Care Mentoring meeting

Examples of governance activities reported

Band 7:

- Postgraduate diploma work at Portsmouth

- Discussion with registrar regarding integrated care pathway for fractured neck of femur

Band 8a:

- E-prescribing learning session

- Completing incident report form

Band 8b:

- Multidisciplinary discussion regarding extravasations guideline

- Guideline validation meeting

- Discussion of governance issue with colleague (MI helpline)

Band 8c:

- Analysing data to support extended hours

- Planning for diclofenac to ibuprofen switch

- Pre-registration audit project preparation

Conclusion

It is feasible to capture clinical pharmacists ‘off-ward’ activities within a context of a structural shift to clinical orientation within hospital pharmacy. The structural shift will require clinical pharmacy leadership through the appointment of more pharmacists in consultant roles.

Future work

This study may open up the possibilities of researching the impact of different clinical pharmacy models on patients’ outcomes and developing benchmarking standards, which may improve the quality and efficiency of service provision.

Key points

- This pilot has demonstrated the feasibility of capturing the off-ward activities of hospital pharmacists within the context of a structural shift to clinical orientation within hospital pharmacy.

- It is impossible to make any inferences from the results because of the small numbers of participants in the pilot but we considered the responses to be sufficiently robust because the results were broadly in line with expected trends: (i) Band 7 hospital pharmacists would be expected to spend a greater proportion of their time on ward relative to Band 8a or higher pharmacists. (ii) The activity mixes for the different bands were broadly in line with expectation.

- This model, when used in conjunction with established intervention tools, could provide a powerful benchmarking framework for hospital pharmacy practice.

References

- Child D, Cooke J, Hey R. Hosp Pharm. Stephens, M. 139–161. Pharmaceutical Press, 2011.

- Cotter SM, Barber ND, McKee M. Survey of clinical pharmacy services in United Kingdom National Health Service hospitals. Am J Hosp Pharm 1994;51:2676–84.

- ACCP. The Definition of Clinical Pharmacy. Pharmacotherapy 2008;28:816–7.

- Hepler CD, Strand LM. Opportunities and responsibilities in pharmaceutical care. Am J Hosp Pharm 1990;47:533–43.

- Barber N. Towards a philosophy of clinical pharmacy. Pharm J 1996;257:289–91.

- Calvert RT. Clinical pharmacy–a hospital perspective. Br J Clin Pharmacol 1999;47:231–8.

- Howard P. A survey of NHS consultant pharmacists in england. Eur J Hosp Pharm Sci Pract 2012;19:251–2.

- NHS Confederation. Key statistics on the NHS. (2015). Available at: www.nhsconfed.org/resources/key-statistics-on-the-nhs.

- RPS. Professional Standards for Hospital Pharmacy Services. 65 (2013). Available at: www.rpharms.com/support-pdfs/hospital-report—final.pdf.

- Grimes TC et al. Collaborative pharmaceutical care in an Irish hospital: uncontrolled before-after study. BMJ Qual Saf 2014;23:574–83.

- Klopotowska JE et al. On-ward participation of a hospital pharmacist in a Dutch intensive care unit reduces prescribing errors and related patient harm: an intervention study. Crit Care 2010;14:R174.

- Miller G, Franklin BD, Jacklin A. Including pharmacists on consultant-led ward rounds: A prospective non-randomised controlled trial. Clin Med J R Coll Physicians London 2011;11:312–6.

- Tomlin M. Medication Errors – Capture and Prevention by Pharmacy. 325 (2011). Available at: www.eprints.port.ac.uk/7140/.

- Williams R, Rose D, McArtney R. Intervention recording in Wales give evidence of pharmacy value. Pharm J 2011;3:92.

- Kahaleh A, Gaither C. The effects of work setting on pharmacists’ empowerment and organizational behaviors. Res Soc Adm Pharm 2007;3:199–222.

- Liu CS, White L. Key determinants of hospital pharmacy staff’s job satisfaction. Res Soc Adm Pharm 2011;7:51–63.

- Malson G. Measuring performance: it’s complicated. Clin Pharm 2014;6. URI: 20066761.