The prostate is an accessory sex organ present only in males. It has a stroma rich in smooth muscle, and glandular elements whose secretions contribute to the seminal fluid.

Benign prostatic enlargement is due to hypertrophy of both the glandular and stromal components. It causes urinary symptoms because the prostate surrounds the first 3cm of the urethra, just below the bladder outflow. This enlargement restricts urine flow and produces secondary effects on bladder activity. About a half of this restriction is due to the size of the enlarged tissue (the static component), and the rest to a dynamic component caused by smooth muscle tension in the prostate.

The resulting symptoms are traditionally divided into those during the bladder-filling phase (frequency, nocturia, urgency and precipitant micturition) and those in the bladder-emptying phase (hesitancy, poor or intermittent flow, terminal dribbling and incomplete emptying of the bladder). The end result of bladder outflow obstruction is retention of urine.

Symptoms in the filling phase are the most bothersome, but such symptoms are not diagnostic of bladder outflow obstruction due to benign prostatic enlargement. They can be caused by age-related changes in the bladder muscle, defective central nervous system control of the bladder (commonly due to cerebrovascular insufficiency) and, in the case of the most troublesome symptom of nocturia, age-related changes in the kidney and cardiovascular system and defective nocturnal production of antidiuretic hormone.

Prostatic hypertrophy is thought to be related to changes in the concentrations of testosterone and other sex hormones around the time of the male menopause. Certainly the process, like growth of the prostate itself, is androgen-dependent. At the end of the 19th century castration was the only available treatment for severe symptoms of prostatic enlargement.

Although the process begins microscopically in men in their 30s, and is present in virtually all men in their 80s, troublesome symptoms rarely occur before 50. One-third of men over this age have some bothersome lower urinary tract symptoms, and by the age of 80 65% have them. Once symptoms begin they progress,(1) but in any individual the rate of progression is unpredictable.

Pharmacological management

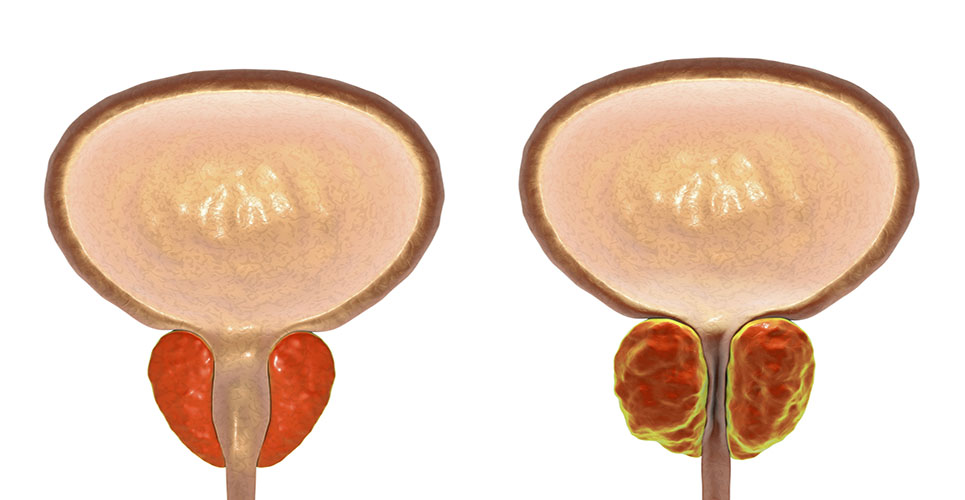

Until about 20 years ago the only option was surgery, to remove the newly enlarged portion of the gland (red portion in Figure 1).

[[HPE06_fig1_74]]

The number of operations to treat benign prostatic enlargement is now about one-third what it was 20 years ago. Half of this reduction is due to the realisation that in many men with lower urinary tract symptoms the prostate is not the cause of the problem, so surgery will not help and can make the situation worse. The other half is due to the availability of pharmacotherapy.

Not all men who attend their family doctor or urologist need treatment. Many have mild symptoms and seek only reassurance that they do not have cancer or that they do not need surgery. Many of these men need no further management: others are “treated” by watchful waiting – monitoring the symptoms, urinary flowrate and efficiency of bladder emptying. One difficulty is in deciding who will progress to the need for surgery, and in particular who may develop acute urinary retention, which is unpleasant and is associated with a higher complication rate after surgery. Overall, a large prostate, a poor urine flow and a high score for troublesome symptoms are associated with a higher risk of acute urinary retention,(2) but prediction for the individual is difficult.

Many men do have bothersome symptoms and need treatment. Surgery has significant side-effects, and except in a very few instances where there are strong indications for surgery, pharmacotherapy is the first choice. Orthodox medicine has two methods of treatment: reduction in size of the newly enlarged portion (ie, reduction in the static component of obstruction) by 5-alpha-reductase inhibitors; and manipulation of the dynamic component by reduction of tension in the prostatic capsule and stroma using alpha-adrenergic blocking drugs.

5-alpha-reductase inhibitors

In prostatic epithelial cells, testosterone is converted to its active metabolite dihydrotestosterone by the enzyme 5-alpha-reductase. This mechanism is not important in testosterone-dependent tissue elsewhere. Inhibiting 5-alpha-reductase deprives the prostate of the hormone it needs without significantly affecting other secondary sex organs.

Currently the only inhibitor available in Europe is finasteride. In clinical trials finasteride reduces prostatic size by, on average, 25%. It increases urinary flow rates and improves symptoms.(3–5) The effects take up to six months to become apparent but have been shown to be maintained for at least six years with continued treatment.(6) About 3% of men develop symptoms of sexual dysfunction, including reduced libido, diminished ejaculatory volume and sometimes erectile dysfunction (which may be secondary to concern about the first two side-effects).

Finasteride is considered by clinicians to be most effective for the larger (more than 40g) prostate where epithelial proliferation (the static component) predominates.

In a study lasting four years, finasteride was shown to reduce the risk of progression to acute retention of urine, and the need for interval surgery by about 55%.(7) However, about 40 men need to be treated to prevent one man developing acute retention of urine.

alpha-adrenergic blocking drugs

Tension in the prostatic tissue (and the internal urinary sphincter) is maintained by sympathetic tone. The receptors involved are of the alpha(1) subgroup. About 25 years ago the alpha-blocker phenoxybenzamine was shown to relax prostatic tissue. Since then a number of more selective alpha-adrenergic blocking drugs have become available, such as:

- Alfuzosin

- Doxazosin

- Indoramin

- Prazosin

- Tamsulosin

- Terazosin.

alpha-adrenergic blocking drugs exert their effect within 48 hours and have been shown to maintain improvement with continued prescription for at least 48 months. They cause significant improvement in urinary flow rates and reduction in symptoms. None of the alpha-blockers has advantages over others in terms of efficacy.

The more selective alpha(1A)-blocker, tamsulosin, may have a reduced incidence of side-effects in some men. Doxazosin has been shown to have side-effects that may be beneficial to men’s general health, including an improvement in lipid profiles and insulin sensitivity, as well as a hypotensive effect for which it was originally marketed. The commonest side-effects of a-blocking drugs are postural hypotension, dizziness, drowsiness and nasal congestion. Because the bladder neck is relaxed by these drugs it may not close efficiently at ejaculation, leading to retrograde ejaculation, which many men find disturbing.

alpha-adrenergic blocking drugs are considered by clinicians to be most effective for the smaller enlarged prostates where the dynamic smooth muscle component predominates.

Combinations of alpha-blockers and finasteride are no more effective than either alone.(8)

Patients on pharmacotherapy should be monitored yearly by symptom scores, urine flowrates and assessment of bladder emptying by postvoid bladder ultrasound. Many will remain satisfied with the improvement for their natural lifespan. A few will progress and need surgery. The concern with the latter group is that prolonged pharmacotherapy followed by surgery is the most expensive way of treating benign prostatic enlargement. Also, delaying surgery for a few years may mean that the patient will be less fit by the time he needs an operation.

Phytotherapy

In addition to the “orthodox” therapies described above, in many parts of Europe treatment with plant extracts is popular.(9) These agents have not been subjected to many clinical trials. An extract of pollen has been shown to inhibit the growth of prostate cells in vitro.(10) The most popular agent is Serenoa repens (Saw palmetto), which does appear to be effective.(11)

Future developments

A new dual-action 5-alpha-reductase inhibitor, dutasteride, is likely to be marketed in Europe in the near future and may have increased efficacy compared with finasteride. alpha-adrenergic blocking drugs with increased selectivity for prostatic tissue are under evaluation. The place of phytotherapy has not been decided.

It is unlikely that we will have major developments in pharmacotherapy for benign prostatic enlargement until we understand more clearly the nature of the cellular processes involved.

Author

Keith Baxby

BSc MB BS FRCS(Eng) FRCS(Ed)

Consultant Urological Surgeon

Tayside University Hospitals

UK

E:[email protected]

References

- Lee AJ, Garraway WM, Simpson RJ, et al. The natural history of untreated lower urinary tract symptoms in middle-aged and elderly men over a period of 5 years. Eur Urol 1998;34:325-32.

- Roehrborn CG, Malice M, Cook TJ, Girman CJ. Clinical predictors of spontaneous acute urinary retention in men with LUTS and clinical BPH: a comprehensive analysis of the pooled placebo groups of several large clinical trials. Urology 2001;58:210-6.

- Andersen JT, Ekman P, Wolf H, et al. Can finasteride reverse the progress of benign prostatic hyperplasia? A 2-year placebo-controlled study. The Scandinavian BPH study group. Urology 1995;46:631-7.

- Gormley GJ, Stoner E, Bruskewitz RC, et al. The effect of finasteride in men with benign prostatic hyperplasia. The Finasteride Study Group. N Engl J Med 1992;327:1185-91.

- Nickel JC, Fradet Y, Boake RC, et al. Efficacy and safety of finasteride therapy for benign prostatic hyperplasia: results of a 2-year randomised control trial (the PROSPECT Study). Can Med Assoc J 1996;155:1251-9.

- Ekman P. Maximum efficacy of finasteride is obtained within 6 months and maintained over 6 years: follow-up of the Scandinavian Open-Extension Study. The Scandinavian Finasteride Study Group. Eur Urol 1998;33:312-7.

- McConnell JD, Bruskewitz R, Walsh P, et al. The effect of finasteride on the risk of acute urinary retention and the need for surgical treatment among men with benign prostatic hyperplasia. N Engl J Med 1998;338:557-63.

- de la Rosette JJ, Alivizatos G, Madersbacher S, et al. EAU guidelines on benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH). Eur Urol 2001;40:256-63.

- Lowe FC, Fagelman E. Phytotherapy in the treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia: an update. Urology 1999;53:671-8.

- Habib FK, Ross M, Buck AC, et al. In vitro evaluation of the pollen extract, cernitin T-60, in the regulation of prostate cell growth. Br J Urol 1990;66:393-7.

- Wilt TJ, Ishani A, Stark G, et al. Saw palmetto extract for treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia: a systematic review. JAMA 1998:280:1604-9.

Meeting

XIII Congress of the European Association of Urology

Madrid, Spain

12–15 March 2003

W:www.uroweb.org