Karl-Johan Lindner and Marie Halvarsson, from the pharmacy at Västerås Hospital in Sweden, describe a new approach to improve the categorisation of medication errors that uses the skills of hospital pharmacists to reclassify reported incidents based on a given medication process.

Most hospitalised patients receive medications during their stay. However, errors related to administering these medicines can occur and they are frequent, avoidable sources of patient harm.

The incidence of medication errors varies greatly among published studies, not only due to the lack of a clear definition,1,2 but also because of different factors such as the healthcare setting, differing levels of automation (e.g. automatic dispensing systems or use of electronic prescribing), the educational level and knowledge of different professional groups, and the chosen methodology for collecting data.3–5

Medication errors are often documented in national or local electronic incident reporting systems.6 Still, some countries, such as Sweden, lack a unified national electronic incident reporting system for these in hospital settings.6

These systems can have many weaknesses, the most significant of which is severe under-reporting,5 meaning that while they help identify risks, they cannot assess patient safety properly.7

A focus on the Västmanland region

The Västmanland region of Sweden has four hospitals with 550 beds in total.

One million injections or infusions and 1.7 million oral solid dosage forms are administered yearly. Regardless of the administration route, medications are administered on approximately 2.6 million occasions.

Approximately 13,000 incidents are reported annually in a standard incident reporting system, of which 5–6% are classified as related to medications. These medication errors are classified within each clinic and rarely at the hospital level; any staff member can report them.

The incident reporting system used in Västmanland is designed to handle a variety of incidents, not just those related to medications. However, the system lacks a straightforward medication process and terminology, such as the taxonomy from the National Coordinating Council for Medication Error Reporting and Prevention (NCC MERP),8 to systematically classify medication errors.

Therefore, we wanted more comprehensive knowledge about where in the medication chain, or in which activities, the risk of different medication errors was most significant.

Our study aimed to develop a new process for reclassifying medication errors and map, at an overall hospital level, where most errors are reported in the medication process.

All incidents reported and classified in 2023 were included in the analysis.

Recording and classifying medication errors

Incidents were reported in the Incident Management System (Synergi Life, DNV, Norway).

The system has several standardised pages or interfaces with dropdown menus, checkboxes and free text fields. The reporter provides a title for the incident and then describes it in a narrative form, focusing on causes, actions, consequences, the course of events and the equipment involved.

Only the date, clinic and narrative information of the case are mandatory for registering and completing the case. The medication involved is categorised according to the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) classification,9 but this is not compulsory to include.

Once recorded, the incident is automatically sent to the responsible person within the clinic or another department for classification and further handling. The system classifies each incident based on fixed choices.

Incidents can be classified, for example, as medication errors, patient-related incidents, or both. Patient-related incidents must be assessed in terms of severity and the risk of recurrence after preventive measures are taken, while medication errors do not need to be classified in terms of severity.

Medication error data extraction and reclassification

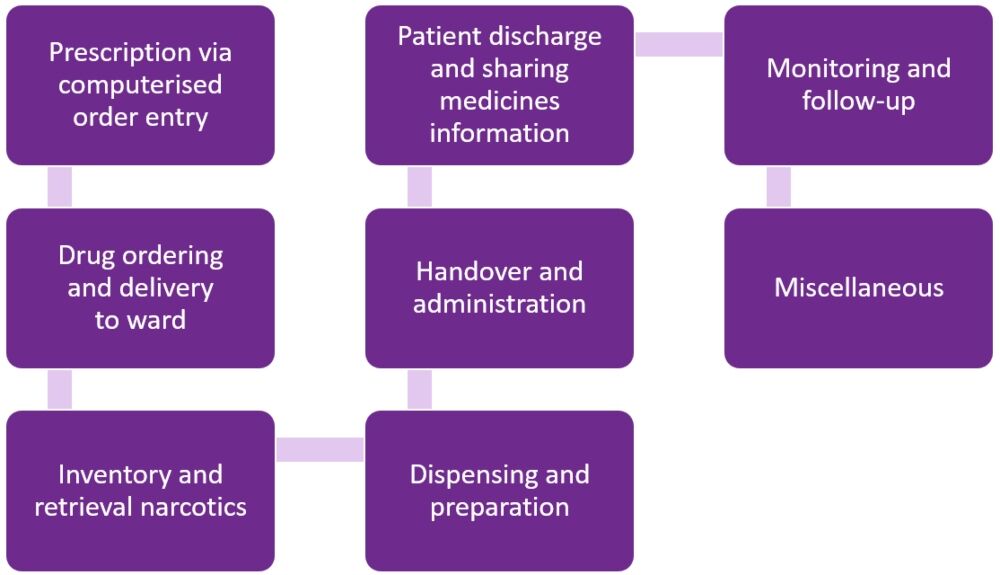

Before the study began, hospital pharmacists developed and validated a structured medication process with eight main categories, each comprising of two to 12 subcategories (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Structured medication process with eight main categories

The electronic incident reporting system identified all incidents classified as medication errors. Data extraction was supplemented with free text searches for the word ‘medication’ in the case title and narrative information for all incidents not initially classified as medication errors. All patient data were anonymised.

Information on the medication errors, their narrative information and classifications were exported to Microsoft Excel for reclassification by two trained hospital pharmacists.

If information such as the route of administration, the medical record system involved and the location of where the incident occurred (e.g. medication room, hospital pharmacy, emergency medication cart) was described, this was also documented in Microsoft Excel.

The data were then visualised using a data processing and performance monitoring tool (SAP Business Objects Web Intelligence).

Results

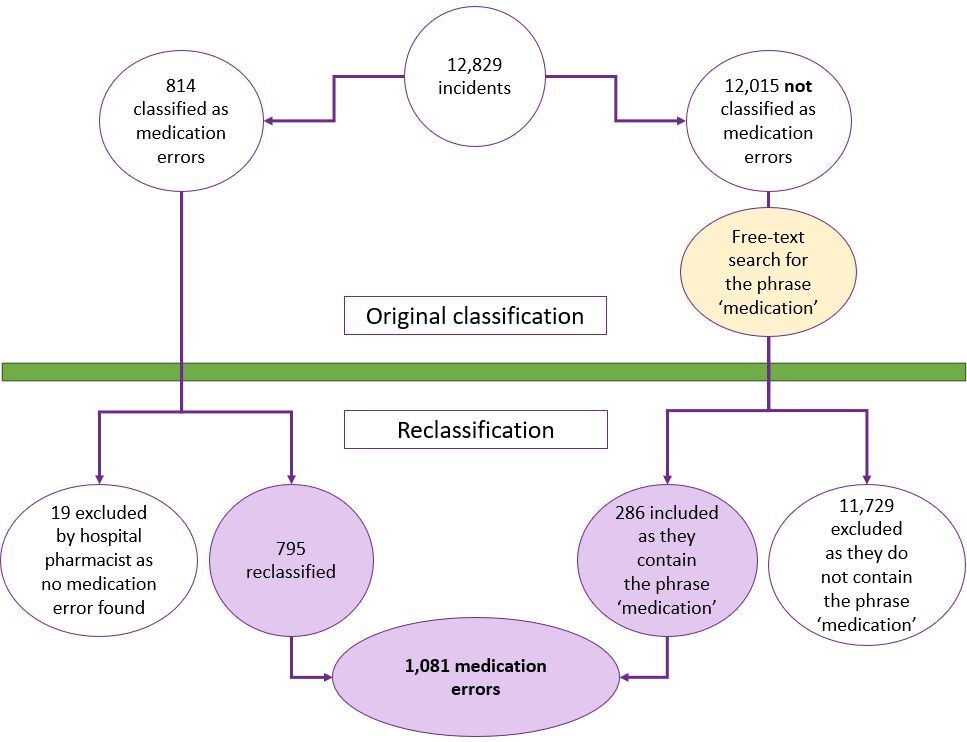

In 2023, a total of 12,829 incidents were reported, of which 814 (6.3%) were initially classified as medication errors (see Figure 2). Of these, 19 (2.3%) were excluded because they were not deemed medication errors upon reclassification by hospital pharmacists.

Figure 2. Flow diagram showing the selection process for medication errors

Free text searches identified an additional 286 medication errors, meaning a total of 1,081 were included in the analysis. Hospitals accounted for 1,011 (94%) of reported errors.

Medications were administered within hospitals 2.59 million times in 2023, giving a medication error report rate of 0.04% of the total number of administrations.

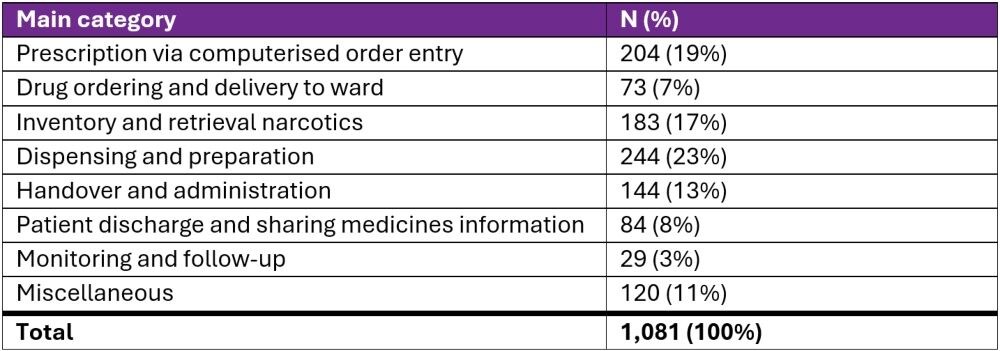

Initially, the medication errors were classified into 82 different activities. The same ones were reclassified according to the structured medication process into eight activities (see Table 1), with preparation dominating (23%), followed by prescription (19%) and storage (17%).

Table 1. Medication error rate by category

The medication or ATC code involved was specified in 68% (738/1,081) of all medication errors. Central nervous system medications or antineoplastic and immunomodulating agents were commonly reported and accounted for 39% (287/738) and 14% (102/738), respectively. Narcotic drugs were involved in 29% (215/738) of medication errors.

Where the route of administration form could be identified (77%, 832/1,081), parenteral drugs accounted for 56% (465/832) of reports.

Discussion

In 2023, a total of 1,081 medication errors were identified and reclassified by hospital pharmacists. Of these, 286 were included after free text searches. As mentioned, medications were administered 2.59 million times during the same period, meaning medication errors were reported in 0.04% of all administrations, consistent with previous data.5

However, observational studies have shown that the incidence of medication errors is 11.7–13.7%, far from what is reported in electronic incident reporting systems.5,10 Relying solely on data analysis from electronic incident reporting systems will vastly underestimate the extent of the problem.

Understanding barriers to error reporting must be considered to increase reporting and the quality of reports, thereby creating opportunities to analyse data more systematically. These include:

- The organisation’s patient safety culture

- Resources

- Awareness of the risks associated with medication handling

- The type and user-friendliness of the incident reporting system support.7,11,12

The present study was not designed to investigate how the parameters above might have influenced the results. Instead, our study shows that a structured medication process is necessary to create a clearer picture of where medication errors occur – or at least in which activities they occur and are reported.

Only when experienced hospital pharmacists analysed and reclassified each reported incident was it possible to identify the activities in the medication process where medication errors occurred.

Most medication errors were reported during preparation (23%), prescription (19%) and storage/inventory (17%). Initially, these three activities were classified in 58 different ways. With a clear definition and taxonomy of medication errors and experienced evaluators, we have shown that the quality of incident report assessments improves, which aligns with other findings.2,13–15

We did not use the taxonomy advocated by NCC MERP,8 which is a limitation should we want to compare our results in the future.

Our results also show that the quality of the content in incident reports must be improved.

Nearly 25% of medication errors lacked information about the route of administration, and just over 30% lacked information about the substance. The involved medication should always be specified, especially for high-risk medications.

It was sometimes difficult to understand what happened from the narrative information. It was also difficult to distinguish between medication errors and ‘near misses’, but, from the narrative information on each case, the assessment is that most medication errors reached the patient. Therefore, we must create better conditions for staff to understand what information needs to be documented while also developing the system to support this.

Pursuing increased medication safety also means managing and analysing more data. If the error rate increases from 0.04%, as the study shows, to 1% of all administrations, it would generate 25,000 medication error reports each year, which would not be manageable regarding resources and quality assurance. Here, artificial intelligence could be a solution.

The technology is increasingly used to identify medication-related problems16,17 and has also successfully been used to analyse medication errors.18

Conclusion

Our study shows that an approach where medication errors are classified without a direct link to a straightforward medication process, and in which many different staff members perform classifications, does not create the conditions for systematic analysis.

The study also shows that the current system for reporting and classifying medication errors needs improvement to work better with them and thus avoid them in the future.

Part of this study data was originally shared as a poster presentation at the European Association of Hospital Pharmacists 28th Congress in March 2024.

Authors

Karl-Johan Lindner MScPharm PhD

Marie Halvarsson BSc

Hospital pharmacy, Västerås Hospital, Sweden

Acknowledgements

The authors thank hospital pharmacists Jenny Calås and Veronica Arwsbo for the reclassification of all medication errors.

References

1 Airaksinen M et al Creation of a better medication safety culture in Europe: building up safe medication practices. 260. Council of Europe 2007;274pp.

2 Lisby M et al. How are medication errors defined? A systematic literature review of definitions and characteristics. Int J Qual Health Care 2010;22:507–18.

3 Risør BW, Lisby M, Sørensen J. An automated medication system reduces errors in the medication administration process: results from a Danish hospital study. Eur J Hosp Pharm 2016;23(4):189–96.

4 Likic R, Maxwell SR. Prevention of medication errors: teaching and training. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2009;67(6):656–61.

5 Flynn EA et al. Comparison of methods for detecting medication errors in 36 hospitals and skilled-nursing facilities. Am J Health Syst Pharm 2002 Mar 1;59(5):436–46.

6 Holmström AR et al. National and local medication error reporting systems: a survey of practices in 16 countries. J Patient Saf. 2012 Dec;8(4):165–76.

7 Pham JC, Girard T, Pronovost PJ. What to do with healthcare incident reporting systems. J Public Health Res 2013;2(3):154–9.

8 NCC MERP Taxonomy of Medication Errors. www.nccmerp.org/sites/default/files/taxonomy2001-07-31.pdf.

9 World Health Organization. Anatomical Therapeutical Chemical (ATC) Classification. www.who.int/tools/atc-ddd-toolkit/atc-classification

10 Jessurun JG et al. Prevalence and determinants of medication administration errors in clinical wards: A two-centre prospective observational study. J Clin Nurs 2023;32(1-2):208–22.

11 Holmström AR, Laaksonen R, Airaksinen M. How to make medication error reporting systems work–Factors associated with their successful development and implementation. Health Policy 2015;119(8):1046–54.

12 Hartnell N et al. Identifying, understanding and overcoming barriers to medication error reporting in hospitals: a focus group study. BMJ Qual Saf 2012 May;21(5):361–8.

13 Forrey RA, Pedersen CA, Schneider PJ. Interrater agreement with a standard scheme for classifying medication errors. Am J Health Syst Pharm 2007;64(2):175–81.

14 Kunac D et al. Inter- and intra-rater reliability for classification of medication related events in paediatric inpatients. BMJ Qual Saf 2006;15:196–201.

15 Holmström AR et al. Inter-rater reliability of medication error classification in a voluntary patient safety incident reporting system HaiPro in Finland. Res Social Adm Pharm 2019 Jul;15(7):864–72.

16 Johns E et al. Using machine learning or deep learning models in a hospital setting to detect inappropriate prescriptions: a systematic review. Eur J Hosp Pharm 2024;31(4):289–94.

17 Ben Othman S et al. Pharmaceutical Decision Support System Using Machine Learning to Analyze and Limit Drug-Related Problems in Hospitals. Stud Health Technol Inform 2024;310:1593–7.

18 Härkänen M et al. Artificial Intelligence for Identifying the Prevention of Medication Incidents Causing Serious or Moderate Harm: An Analysis Using Incident Reporters’ Views. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021;18(17):9206.