teaser

Peter Malfertheiner

MD

Professor

Gerhard Treiber

MD

Department of Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Infectious Diseases

Otto-von-Guericke University

Magdeburg

Germany

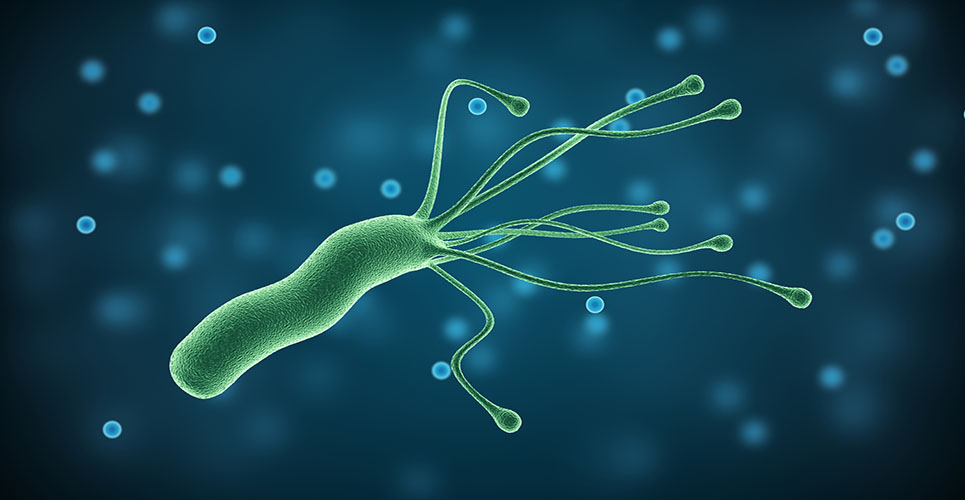

The discovery of Helicobacter pylori and the recognition of its pivotal role in gastric and duodenal ulcer (GU/DU) pathogenesis stimulated the search for further Helicobacter species in the gastrointestinal tract as candidates related to hepatobiliary diseases and inflammatory bowel diseases. Although a large number of species belonging to the genus Helicobacter have been discovered in humans and animals during the past decade, there is still no clinical data for a causal link between new Helicobacter species and other gastrointestinal diseases.(1)

In human pathology, research is now focusing on diseases associated with H pylori, with several therapies available.(2) The major interest, however, lies in the understanding of the mechanisms through which H pylori contributes to gastric carcinogenesis and in defining strategies for prevention.

In this report, aspects of the current clinical management of H pylori infection are first addressed. New developments in the role of H pylori in gastric cancer, with implications for clinical management, will then be discussed.

Current clinical management

After years of experimental and often individualised approaches to the management of H pylori infection, physicians, particularly in primary care, were in considerable need of guidance. Burning questions needed to be tackled regarding indications for therapy and testing procedures to be used. Furthermore, disparate treatment regimens needed to be harmonised. In 2000, the European Helicobacter Pylori Study Group (EHPSG) organised a conference in Maastricht considering all clinical data available, with the aim of updating European consensus guidelines for the treatment of H pylori. The key issue was to identify all relevant research results that could be used for clinical practice.(2)

Patient management in primary care

Most individuals infected with H pylori in whom eradication therapy could be beneficial seek help from primary care physicians. “Test and treat” is recommended as the first option for the management of young dyspeptic patients without alarm symptoms. The (13)C-urea breath or the stool antigen tests, but not serology, are recommended for this purpose. The sensitivity and specificity of serology are considered less standardised and reproducible, in addition to not being fully reliable for distinguishing current from previous infections.

The critical consideration for adopting a noninvasive test in primary care is the cutoff age (younger than 45 years) and no associated alarm symptoms. In addition, the geographical area in which the strategy is adopted should have a low prevalence of gastric cancer in the younger age group, or the cutoff may be set higher if gastric cancer occurs at a more advanced age.

The “test and treat” strategy is cost-effective if H pylori infection prevalence in the population is not <20% and if malignancy is rare in this age group. It is strongly recommended, however, that patients over the age of 45 years (or up to 55 years in other areas) with significant dyspeptic symptoms and/or with alarm symptoms (irrespective of age) should be referred to a specialist to exclude malignancy.

Indications for H pylori eradication

If patients are seen by a specialist and endoscopic examinations are performed, indications for therapy are set at three levels: strongly recommended, advisable and not recommended (ie, uncertain), based on different strengths of supporting evidence.

H pylori eradication is strongly recommended in all infected patients with peptic ulcer disease (PUD), whether active or in remission, and this recommendation includes patients with bleeding peptic ulcers.

Eradication therapy is also strongly recommended in patients with low-grade gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma (in whom eradication has been reported to lead to complete remission of the malignancy in 74% of cases),(3) in patients with atrophic gastritis and following early resection for gastric cancer. A family history of gastric cancer also makes first-degree relatives candidates for eradication therapy. Finally, patients expressing their wishes to be tested for this gastroduodenal risk factor should be tested and treated on a case-by-case basis.

Due to some equivocal evidence to support the recommendations, the Maastricht guidelines state that eradication therapy is considered advisable in patients with functional dyspepsia, after careful exclusion of other pathologies, in patients for whom treatment with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) is planned or ongoing or in those who undergo long-term profound acid suppression (mainly patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease [GORD]).

The rationale behind the recommendation to eradicate H pylori in patients with functional dyspepsia includes the prevailing benefit shown by long-term studies and circumstantial evidence that, once the risk factor has been removed, an important load of future gastroduodenal pathology is prevented. The measure is apparently cost-effective. Results from more recent studies indicate that subsets of patients such as those with epigastric pain or with more severe pain obtain more substantial benefit from H pylori eradication. Although the number-needed-to-treat in H pylori-associated functional dyspepsia may be around 12, an advantage is still present, as there is no superior treatment available. In addition, some patients are protected from peptic ulcer disease or malignancies that could develop in the future.

Evidence in the medical literature regarding the nature of relationship between H pylori infection and NSAID is conflicting and complex. Ulcer incidence in patients taking NSAIDs is decreased if eradication is performed before first use of an NSAID. Moreover, if H pylori is eradicated, patients are less likely to acquire dyspeptic symptoms. Healing of an already established gastric ulcer is not enhanced by H pylori eradication, compared with a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) alone, or may even be slightly delayed. Following ulcer complications (such as bleeding), eradication alone is not sufficient and PPI treatment needs to be continued in the long term. Aspirin-induced lesions in the presence of H pylori-infected gastric mucosa are subject to different pathomechanisms and appear to respond better to H pylori eradication, compared with NSAIDs. However, eradicating H pylori and continuing treatment with a PPI in patients with aspirin-induced gastroduodenal lesions is the perfect approach.(4)

Eradication of H pylori is also advised in patients receiving long-term antisecretory treatment for GORD in whom there has been concern that H pylori may accelerate gastric atrophic changes. Although this is a much-debated issue, the available prospective studies provide results of different magnitude as to the development of atrophic changes in H pylori-positive patients. To what extent atrophy is accelerated with long-term antisecretory treatment may be discussed, but the gastritis phenotype shifts from antral-predominant to fundus-corpus-predominant gastritis.

The hypothesis that H pylori protects the oesophagus is mainly derived from epidemiological associations and uncontrolled, mostly retrospective, clinical observations. Although several recent prospective studies do not confirm earlier observations that eradication leads to an increased risk of GORD, this debate continues to animate scientific and educational events.

An emerging issue is the relationship between H pylori and extra-alimentary disorders, such as cutaneous manifestations (urticaria, rosacea or rheumatoid arthritis), but no definitive advice can be given for these conditions. Decisions for H pylori therapy in these conditions needs to be taken on a case-by-case basis.(5)

Gastric carcinogenesis and cancer prevention

The major threat from H pylori infection remains gastric cancer. The disease usually occurs at a more advanced age (>50 years) and is not generally curable (~85%) at the time of clinical presentation. Frequently, there are no premonitoring symptoms and, therefore, prevention strategies offer the best chance. H pylori testing (with treatment in the case of a positive result) in dyspeptic patients, although an important strategy, would not enable the prevention of gastric cancer in a large number of patients, as many are not dyspeptic before gastric cancer becomes apparent.

“Screen and treat” would be the best option, but this type of strategy would involve a huge expenses burden, which is currently not acceptable for health regulatory agencies. Thus, the best approach is still “test and treat”, and additional “search and treat” in a subset of patients at risk.

According to epidemiological data, approximately 70% of distal gastric cancer can be attributed to H pylori.(6) The evidence for H pylori as the most important risk factor in gastric cancer is based on biological plausibility and on the beneficial effects of eradication on conditions and lesions of the stomach mucosa that precede gastric cancer. Few observational studies confirm the protective effect of H pylori therapy against gastric cancer.(7) The most critical aspect is that some lesions (atrophy and intestinal metaplasia) that can potentially lead to gastric cancer do not regress following successful eradication. Therefore, early intervention in H pylori infection is recommended.

As only a subset of colonised individuals develop malignant H pylori-related disease, the major challenge is currently to identify patients with a potential familial risk and with a predominant corpus atrophy (if patients undergo endoscopy). Microbial virulence (such as CagA [pathogenicity island] or VacA [vacuolating cytotoxicity]) and host factors (such as functional polymorphisms in the IL-1beta and TNF-alpha genes), in addition to the environment, seem to determine which groups of individuals are predisposed to the disease.

Many challenges need to be resolved to translate the current basic knowledge into important clinical gain. These include a better definition of the subjects at risk, identifying the point of no return in the pathway of gastric carcinogenesis despite H pylori eradication and developing novel therapies (the “golden bullet”).

Treatment of H pylori infection

Over the years, there has been substantial improvement in the treatment of H pylori infection, and the effectiveness of eradication if treatment is appropriately performed is currently ~90%. The main reasons for treatment failure include noncompliance, side-effects, resistance to antibiotics, insufficient dosage of the drugs used, unapproved or ineffective treatment combinations, and clinical disease presentation (as a marker for CagA). While there is a clear association with treatment failure in the case of macrolide resistance, the situation for imidazole resistance is much more complex, and clinical importance depends on the dosage of metronidazole applied, smoking status and resistance-modulating co-medication.(8) A common side-effect is diarrhoea, mainly due to amoxicillin; taste disturbances are less commonly observed with macrolides and metronidazole, and allergies are a rare problem. The rationale for acid inhibition, in addition to improved healing of potential lesions by PPIs, is based on an improved stability of antibiotics (clarithromycin, amoxicillin) and on their local concentrations being further increased through a reduced gastric mucus volume.

First-line treatment consists of the combination of a PPI and clarithromycin, in addition to either amoxicillin (PPI-C-A) or metronidazole (PPI-C-M) for 1 week.(2) The choice of regimen can be made by an adequate assessment of the actual or expected antibiotic resistance of H pylori and individual patient factors. As a rule, PPI-C-A should be preferred over PPI-C-M, because the pre-existing resistance of H pylori to metronidazole in about one-third of patients can be neglected. In addition, primary resistance against amoxicillin is extremely rare and is not even induced in the case of failure.

PPI-C-M, the second-best choice, is used in the case of amoxicillin allergy. PPI-C-M can be applied with a daily dose of clarithromycin (500mg; 1,000mg necessary for PPI-C-A). This combination is even more effective in the case of premature termination of drug intake (compliance), with the rate of diarrhoea being lower. Despite positive study reports of 1–5-day regimens, 1 week should be the standard, as acceptable eradication rates with short-term regimens were predominantly obtained with quadruple therapies only.(2)

Eradication outcome should always be monitored by adequate diagnostics (PPIs, bismuth and antibiotics should be kept off for 2 weeks before). This can be achieved either by biopsy-based testing (rapid urease test and histology) or noninvasively by urea breath or stool antigen tests.

In the case of documented failure, second-line therapy should be applied using a 1-week PPI–bismuth– metronidazole–tetracycline regimen. Interestingly, this regimen has proven effective even under the conditions of metronidazole resistance. Subsequently, any further attempt must be managed by a qualified gastroenterologist.

Options include resistance-guided individualised therapy (the best choice), PPI–amoxicillin–rifabutin (1 week), PPI–amoxicillin (high-dose, 2 weeks), PPI–bismuth– tetracycline–furazolidone (1 week) or triple therapy including PPI–amoxicillin–levofloxacin or moxifloxacin (less investigated). If PPI-A-C is reused because of proven lack of clarithromycin resistance, we recommend this therapy for 10–14 days.(9,10)

References

- Andersen LP. Dig Dis 2001;19:112-5.

- Malfertheiner P, Megraud F, O’Morain C, et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2002;16:167-80.

- Zucca E, Cavalli F. Curr Hematol Rep 2004;3:11-6.

- Isakov V, Malfertheiner P. Helicobacter 2003;8:36-43.

- Gasbarrini A, Carloni E, Gasbarrini G, et al. Helicobacter 2003;8:68-76.

- Brenner H, Arndt V, Stegmaier C, et al. Am J Epidemiol 2004;159:252-8.

- Uemura N, Okamoto S, Yamamoto S, et al. N Engl J Med 2001;345:784-9.

- Wong BC, Lam MK, Wong WM, et al. JAMA 2004;291:187-94.

- Malfertheiner P, Peitz U, Treiber G. Can J Gastroenterol 2003;17:53-7.

- Treiber G, Ammon S, Malfertheiner P, et al. Helicobacter 2002;7:225-31.

- Peitz U, Sulliga M, Wolle K, et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2002;16:315-24.