Depots, long-acting second-generation antipsychotic injections and oral medication as maintenance treatment in established schizophrenia are discussed.

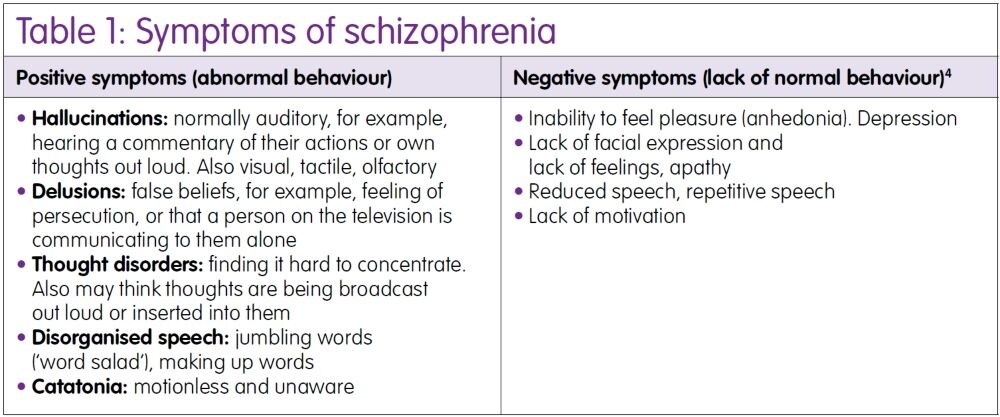

Schizophrenia is a long-term mental health condition affecting approximately 0.3–0.7% of people throughout the course of their lifetime worldwide.1 It is diagnosed after evaluation of a range of psychological symptoms (Table 1).

As 50% of people living with schizophrenia try to commit suicide, and up to 10% of these die by suicide, it is important to find an effective and tolerable treatment.2,3 Diagnosis is based on assessment of clinical symptoms, usually by a psychiatrist.

Schizophrenia is a major cause of disability, and it is thought that 75% of people living with schizophrenia experience long-term disability comprising relapses and decreased functioning overall.1 It is important to encourage patients to recognise relapse signatures – these can include changes in concentration levels, sleep patterns or in appetite, and also anxiety, suspiciousness, and the recommencement or increase in the frequency and intensity of auditory and visual hallucinations.

Treatment options

The goals of treatment are about maintaining the person’s wellbeing, social functioning and physical health care. According to the latest guidance on schizophrenia from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE; which applies in England and Wales), treatment should comprise a combination of medication and talking therapy (for example, cognitive behavioural therapy, family and arts therapy).5,6

In addition, written care plans are useful in aiding prevention and relapse recognition. The care plan would ideally also document preference regarding the use of medication. It is much more effective for a person to take the medication regularly to prevent relapse, rather than taking it intermittently.7

Antipsychotics

The mainstay of pharmacotherapy in schizophrenia is antipsychotic medication. First-generation and second-generation gradations are no longer seen as indicative in terms of either efficacy or tolerability.3

- Mechanisms of action

Antipsychotics work mainly by antagonising dopamine receptors (although most also have affinity for other neurotransmitter receptors). In the case of aripiprazole there is a stabilising effect on dopamine receptors (partial agonist receptor profile). This antagonism of dopamine can be sedating so may calm patients.

They can cause extrapyramidal side effects (EPSEs) by reducing the levels of dopamine in the striatum causing Parkinson-like symptoms and akathisia. A drug should be tried for at least four to six weeks. They may take weeks to reduce hallucinations and delusions but should reduce anxiety sooner. The effects usually become evident within a couple of weeks after initiation.

- Withdrawal

Withdrawal of antipsychotic medication should be gradual, with close monitoring because of the risk of relapse. Patients should be monitored for two years after stopping antipsychotic medication.

Oral medication is usually trialled before the option of using injectable medication is explored.

Those newly diagnosed with schizophrenia and those experiencing an acute episode should be offered oral antipsychotics. Acute symptoms respond better than chronic. The risks and benefits should be discussed with the patient and family.

- Choice of medication

NICE recommends that the choice of antipsychotic medication should take into account the views of the patient, on the benefits and side effect profile of the medication. This includes the propensity to cause unpleasant subjective experiences. Choosing a drug could depend on factors such as the potential to cause EPSE, and sexual side effects linked to increased levels of prolactin, or weight gain. An ECG should be offered if indicated in the Summary of Product Characteristics or if the patient has a history, or risk, of cardiovascular disease.

Prescribers should gradually titrate up to an effective dose. The drug is taken until the acute episode passes but evidence supports continuing for one to two years after to prevent relapse.5

Second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) include clozapine, quetiapine, lurasidone, risperidone and amisulpride. First-generation antipsychotics (FGAs) include chlorpromazine, sulpiride and haloperidol.

- Cautions and contraindications

Caution is recommended in patients with cardiovascular disease, Parkinson’s disease (exacerbated), epilepsy, glaucoma, prostatic hypertrophy and blood dyscrasias. Care should also be exercised when prescribing for elderly patients, and dementia patients due to the possible side effect of hypo/hyperthermia, hypotension and increased risk of stroke.8 Contraindications should be noted and may include recent heart surgery or history of myocardial infarction.

- Side effects

EPSEs, such as tremor, bradykinesia, abnormal face and body movements and muscle rigidity. FGAs have the most pronounced EPSEs, for example, haloperidol, prochlorperazine and fluphenazine. Side effects include:

- Hypotension (dose dependent)

- Hypo/hyperthermia (dose dependent)

- Hyperprolactinaemia with breast enlargement and lactation affecting both men and women. Patients may also experience sexual dysfunction (male and female) and menstrual disturbances in females

- Neuroleptic malignant syndrome is rare but fatal and signs include hyperthermia, fluctuating consciousness, muscle rigidity and tachycardia

- ECG changes such as prolonged QT interval, which could lead to ventricular arrhythmias and sudden death. Care is needed with patients at additional cerebovascular risk, such as a history of stroke

- Drowsiness, apathy, agitation, antimuscarinic symptoms, for example, constipation and blurred vision, weight gain and diabetes (although may be related to pre-existing lifestyle)

- Blood dyscrasias.

Clozapine

Clozapine is used for treatment-resistant schizophrenia, which is when treatment with at least two antipsychotics (one must be an SGA) for a course of at least six to eight weeks at an adequate dose does not reduce the symptoms effectively. Clozapine can cause agranulocytosis and neutropenia and so blood tests are required weekly for 18 weeks, fortnightly for up to 52 weeks and four-weekly thereafter.

Signs of blood dyscrasias include flu-like symptoms, sore throat, fever and bruising.5 Clozapine is associated with severe constipation leading to bowel obstruction and cardiomyopathy. In spite of how difficult it is to use, and the fact that it is only available as an oral formulation in the UK, it is the mainstay of treatment-resistant schizophrenia.5

Parenteral options

Patients may prefer parenteral medication for reasons of assurance and convenience. Disadvantages include inflexibility in terms of dose adjustments and the fact that it may be used as part of a treatment plan that has been imposed (perhaps through mental health legislation such as the Mental Health Act 1983 (revised in 2007)) in England and Wales.8

There are FGA and SGA long-acting choices, most being administered between two- and four-weekly intervals.9 Depot injections of FGAs may lead to higher incidence of EPSEs than the corresponding oral treatment but are considered an established and cost-effective option. The use of olanzapine embonate in practice has been limited by the need to observe patients post-administration due to the risk of post-injection syndrome.

For some services, it is a challenge to be able to use this medication safely. Risperidone long-acting injection (LAI) requires the administration of oral cover for four to six weeks on initiation due to its delayed release characteristics. Paliperidone LAI is a similar product pharmacologically and easier to use in practice, with monthly injections and no cold chain required.

A formulation of paliperidone palmitate that is administered once every three months is now available. In terms of patient choice and convenience, this seems to be a useful option in selected patients, as an optimum therapeutic drug level can be maintained with fewer administrations, compared with other antipsychotic treatments. The new formulation is indicated for the maintenance treatment of schizophrenia in adult patients who are clinically stable on the monthly LAI.

Aripiprazole is also available as a monthly LAI and offers an option especially for those intolerant of prolactin-related side effects. An excellent administration guide on depots and LAIs is available for further reading.10

Patient choice

It is important that patients are able to play a full role in their own therapeutic choices. It is common for UK mental health Trusts11 to employ an approach that involves enablement of the patients. It requires that service providers build on an individual’s strengths and develop resilience. One of these strategies is encouraging adherence to medication; in order to support adherence, it is important that solutions to issues such as adverse effects are explored in a collaborative manner.

Conclusions

In exploring maintenance treatment options in schizophrenia, the patient needs to be at the front and centre of all discussions about treatment. Recent workstreams have included highlighting the importance of monitoring the physical health of those living with schizophrenia and also raising the profile and funding of mental healthcare to be on par with physical healthcare services.5,12

We work toward providing enablement, recovery, optimism and hope – this is important for people taking medication long-term who, while not always suffering from symptoms, will experience side effects. The patient should be empowered to make informed choices around medication and be informed about the likelihood of adherence to a particular treatment. The patient is an active partner in their care wherever insight and the severity of the illness allows.

Medicines optimisation is a helpful model to follow, in that a patient-centric view is required; this way, we can look at the possible rather than options that prove to be unworkable. Specialist mental health pharmacists and technicians work across Europe and are a useful resource for patients. They may be attached to community mental health teams. In fact, people living with schizophrenia should have access to a specialist pharmacist for advice and all possible practical support.

Key points

- Treatment options include pharmacotherapy but are not limited to it – the goal is to function as well as possible in terms of what is important to the patient in rating their quality of life

- Antipsychotic medication is still the mainstay of maintenance pharmacotherapy of schizophrenia

- The views of the patient are crucial to the choice of medication. Consultations should allow both practitioner and patient to explore and rate options

- Choices should be made in partnership based on tolerability, efficacy, safety and likelihood of adherence

- There are a number of oral and parenteral options available, including long-acting injections.

Author

Katrina Powell BPharm(Hons) MRPharmS DipPsychPharm

Barnet, Enfield and Haringey Mental Health NHS Trust, London, UK

The author reports no declarations of interest.

About the CMHP

Pharmacists and technicians have been supported for many years by the College of Mental Health Pharmacy. The College provides an international community for pharmacy staff working in mental health, has a credentialing service to raise and maintain standards of care, and promotes research in pharmacotherapy of mental health conditions. Please see: www.CMHP.org.uk for further details (KD is a member of CMHP).

References

- van Os J, Kapur S. Schizophrenia. Lancet 2009;374(9690):635–45.

- Palmer BA et al. The lifetime risk of suicide in schizophrenia: a reexamination. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2005;62:247–53.

- Lieberman JA et al. For the Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) Investigators. Effectiveness of antipsychotic drugs in patients with chronic schizophrenia. N Engl J Med 2005;353:1209–23.

- Sicras-Mainar A et al. Impact of negative symptoms on healthcare resource utilization and associated costs in adult outpatients with schizophrenia: a population-based study. BMC Psychiatry 2014;14:225. DOI: 10.1186/s12888-014-0225-8 [online].

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Clinical guideline CG178. Psychosis and schizophrenia in adults: prevention and management. www.nice.org.uk/Guidance/cg178 (accessed October 2016).

- Jones C et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy versus other psychosocial treatments for schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Sys Rev 2012;4:CD008712.

- Sampson S et al. Intermittent drug techniques for schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Sys Rev 2013;7:CD006196.

- Mental Health Act 2007. www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2007/12/contents (accessed October 2016).

- British National Formulary. September 2016. Pharmaceutical Press.

- Feetam C. Guidance on the administration of oil-based depot and other long-acting intramuscular antipsychotic Injections. www2.hull.ac.uk/fhsc/pdf/SOP_Final_2014_PDF.pdf (accessed October 2016).

- Barnet, Enfield and Haringey Trust. BEH enablement strategy. www.beh-mht.nhs.uk/Communications/BEH%20Enablement%20Strategy%202015.pdf (accessed October 2016).

- Parliamentary Office of Science and Technology. Parity of Esteem for Mental Health (485). January 2015;UK. http://researchbriefings.parliament.uk/ResearchBriefing/Summary/POST-PN-485 (accessed October 2016).