The term ‘atopy’ describes a genetic predisposition to develop allergic symptoms that affect the skin, gut, sinuses and airways. Typically, cutaneous symptoms develop first, followed by food allergies, allergic rhinitis and finally asthma in what is described as the ‘atopic march’.1

The term ‘atopy’ describes a genetic predisposition to develop allergic symptoms that affect the skin, gut, sinuses and airways. Typically, cutaneous symptoms develop first, followed by food allergies, allergic rhinitis and finally asthma in what is described as the ‘atopic march’.1

Atopic eczema (AE), also known as atopic dermatitis (the initial presentation of atopy) is a long-term, pruritic inflammatory skin condition, affecting approximately 20% of children. In nearly half of those affected, symptoms develop within the first year of life, with 95% experiencing onset before five years of age.2 Moreover, AE persists into adulthood in up to 3% of the population.3 Typically, symptoms include inflamed, dry, cracked, scaly skin, normally in elbow and knee creases, and the condition becomes more chronic in adults, with inflamed, thickened plaques affecting the hands and face.

Pathophysiology

The cause of AE remains unclear, although is likely to be a combination of altered skin barrier function and immune dysregulation. Which aberration initiates events remains unclear and two opposing theories have been proposed. The ‘outside-in’ theory4 suggests that a genetic susceptibility produces a defective skin barrier, permitting the entry of allergens or irritants, thereby provoking an inflammatory response. Support for this theory arose from the discovery in 2006 that loss-of-function mutations in the gene that codes for filaggrin (FLG) was the underlying cause of ichthyosis, a dry skin condition, and that these mutations were a predisposing factor for AE.5 Filaggrin is a protein required for the production of an intact skin barrier and its amino acids contribute to the natural moisturising factor that helps maintain skin hydration.6 However, not all patients with FLG mutations develop AE and the alternative ‘inside-out’ hypothesis proposes that a dysfunctional immune response induces local inflammation, leading to the development of a defective skin barrier.7

Irrespective of the precise order of events, two cytokines – interleukin (IL) 4 and 13 – produced by Th-2 immune cells, have an important role in the initiation of AE symptoms and act via the same receptor, namely IL-4Ra.8 This discovery has stimulated a search for agents that block the receptor with a view to ameliorating the symptoms of AE.

Management

Currently, mild to moderate disease is managed with emollients and topical steroids or calcineurin inhibitors. Unresponsive patients or those with more widespread disease are treated with either phototherapy or systemic agents.9 However, a recent review observed that while systemic agents are effective, all are associated with problems that limit their use.10 Consequently, a range of other agents have been investigated11 and one that has emerged and shown potential is dupilumab.

Dupilumab

Dupilumab is a human monoclonal antibody that was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration in March 2017 for the management of adults with moderate to severe AE uncontrolled with topical therapies and granted a marketing authorisation from the Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use in July 2017. As such, it is the first biologic agent for AE and represents an important therapeutic advance in the management of patients with more recalcitrant disease.

Clinical studies

There are no ‘gold standard’ assessment tools for AE and several different instruments have been used and the most common ones have been described by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE).9 Many trials use either the Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI), SCORAD or an investigator global assessment (IGA), which evaluates severity on a scale from 0 (clear) to 4 (most severe). Investigators often report EASI50 or 75, that is, the proportion of patients achieving a 50% or 75% reduction in EASI score.

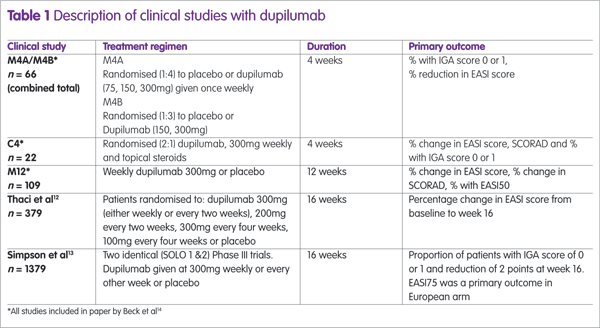

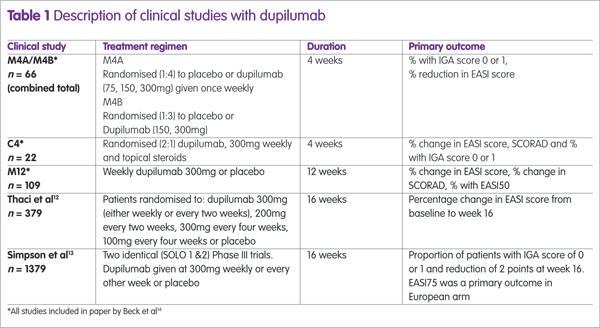

Dupilumab has been assessed in several clinical trials, either as monotherapy or combined with topical steroids (see Table 1). The largest studies were two identical Phase III trials (SOLO1 and SOLO2) and the proportion of patients achieving an EASI75 in these trials12 are shown in Figure 1, from which it can be seen that there is no difference between dupilumab given weekly or every other week (alt weeks in Figure 1).

Longer-term data

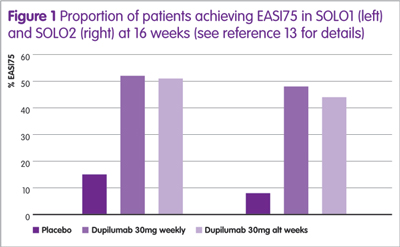

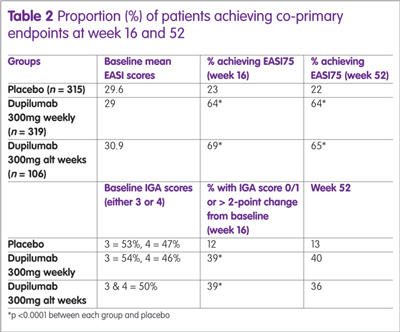

Recently, the results of a 52-week, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study with dupilumab have been published.15 The study enrolled 740 patients who were assigned to dupilumab (300mg weekly), 300mg every other week (alt week) or placebo. All were permitted to use medium to low potency topical steroids if required. There were two co-primary endpoints; IGA of 0 or 1 (clear/almost clear); or a >2-point change from baseline and the proportion of patients achieving an EASI75 at week 16. A secondary endpoint was the proportion of patients achieving an EASI75 at week 52. A summary of the results is shown in Table 2.

Adverse events

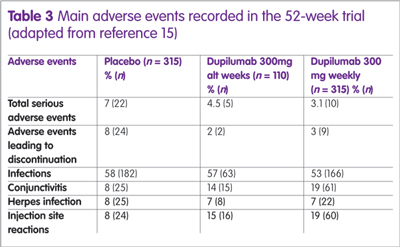

A summary of the main adverse events observed in the 52-week study are shown in Table 3. The reason for the high level of conjunctivitis is unclear, although symptoms were mild in the majority of patients.

Conclusions

While experience to date with dupilumab is limited, the available data suggest that the drug is an effective therapy for those with moderate to severe disease. However, there are currently no clinical trials comparing the drug with existing oral therapies or in the paediatric population, which represents the majority of patients with AE. Nevertheless, as more real-world and trial evidence emerges, it is likely that dupilumab will become a valuable addition to the therapeutic armamentarium for those with moderate to severe AE unresponsive to topical therapies.

Key points

- Atopic eczema is an inflammatory skin condition affecting up to 20% of children and 3% of adults.

- The condition is managed with topical therapies and either phototherapy or systemic agents for those with more widespread and severe disease.

- Dupilumab is a human monoclonal antibody treatment for patients with moderate to severe atopic eczema unresponsive to topical therapy.

- Studies suggest that dupilumab has an excellent safety profile and completely clears symptoms in up to 40% of patients after four months.

- Future studies comparing dupilumab with existing therapies are warranted to define its position in the management of people with moderate to severe atopic eczema.

References

1 Bantz SK et al. Epidemiology and natural history of atopic diseases. Eur Clin Respir J 2015;2:1–6.

3 Nutten S. Atopic dermatitis: Global epidemiology and risk factors. Ann Nutr Metab 2015;66:8–16.

4 Elias PM, Steinhoff M. “Outside-to-inside” (and now back “Outside” pathogenic mechanisims in atopic dermatitis. J Invest Dermatol 2009;128(5):1067–70.

5 Akiyama M. FLG mutations in ichthyosis vulgaris and atopic eczema: Spectrum of mutations and population genetics. Br J Dermatol 2010;162(3):472–7.

6 Brown SJ, McLean WH. One remarkable molecule: Filaggrin. J Invest Dermatol 2012;132(3):751–62.

7 Hanifin JM. Evolving concepts of pathogenesis in atopic dermatitis and other eczemas. J Invest Dermatol 2009;129(2):320–2.

8 Gandhi NA, Pirozzi G, Graham NMH. Commonality of the IL-4/IL-13 pathway in atopic diseases. Expert Rev Clin Immunol 2017;13(5):1–13.

9 National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Atopic eczema in under 12’s: Diagnosis and management [Internet]. www.nice.org.uk/guidance/CG57/chapter/1-Guidance#treatment (accessed December 2017).

10 Ring J et al. Guidelines for treatment of atopic eczema (atopic dermatitis) Part II. J Eur Acad Dermatology Venereol 2012;26(9):1176–93.

11 Walling HW, Swick BL. Update on the management of chronic eczema: new approaches and emerging treatment options. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol 2010;3:99–117.

12 Thaçi D et al. Efficacy and safety of dupilumab in adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis inadequately controlled by topical treatments: A randomised, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging phase 2b trial. Lancet 2016;387(10013):40–52.

13 Simpson EL et al. Two phase 3 trials of dupilumab versus placebo in atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med 2016;375(24):2335–48.

14 Beck L et al. Dupilumab treatment in adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med 2014;371(2):130–9.

15 Blauvelt A et al. Long-term management of moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis with dupilumab and concomitant topical corticosteroids (LIBERTY AD CHRONOS): a 1-year, randomised, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2017;389(10086):2287–303.