By using gain-share agreement, cost savings generated from switching Remicade® to biosimilar infliximab can be distributed between clinical services and commissioners, and used to deliver higher quality patient care alongside benefits to the tax payers

Violeta Razanskaite MRCP

Fraser Cummings DPhil FRCP

University Hospital Southampton NHS Foundation Trust, Southampton, UK

Email: [email protected]

By using gain-share agreement, cost savings generated from switching Remicade® to biosimilar infliximab can be distributed between clinical services and commissioners, and used to deliver higher quality patient care alongside benefits to the tax payers

Violeta Razanskaite MRCP

Fraser Cummings DPhil FRCP

University Hospital Southampton NHS Foundation Trust, Southampton, UK

Email: [email protected]

Infliximab is a chimeric monoclonal tumour necrosis factor alpha (TNF-?) antibody licensed by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medicines Agency (EMA) to treat a number of chronic inflammatory conditions including Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. The originator molecule is manufactured by Janssen/MSD and branded as Remicade®, with global sales of over £6.7 billion in 2014.1

The first biosimilar infliximab (CT-P13, manufatured by Celltrion) has been recently licensed by the EMA; a biosimilar is a biological medicine that is developed to be similar to an existing medicine (the ‘reference medicine’/‘originator’).2,3 The active substance of a biosimilar and its reference medicine is essentially the same biological substance, although there may be minor differences due to their complex nature and production methods. The EMA has licensed CT-P13 for the same indications as Remicade® using data from randomised, controlled, double-blind clinical trials in rheumatoid arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis, which showed equivalent outcomes between originator infliximab and CT-P13.4,5 The EMA license for their use in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) has been granted based on extrapolation from these existing rheumatology studies.

Efficient use of high-cost drugs

There are wide variations within the National Health Service (NHS) in the UK, but also within countries in Europe, in the processes for the negotiating the cost of drugs as well as in reimbursement systems. This can lead to disincentives for secondary care providers to deliver cost effective changes in clinical practice, particularly where changes require the commitment of additional resources to manage the change and there are no clear systems to share the benefits accrued. In order to address these issues, gain-share agreements have been developed within the NHS to encourage secondary care providers to make the most efficient use of high-cost drugs. The purpose of gain-share is to incentivise quality improvements and better outcomes for patients while improving efficiency and value for money for the local health economy. This is achieved by seeking the most clinically and cost effective medicines and reinvesting the savings in the clinical areas from which they were attained. The value of gain-share agreement is based on the risk, resource and investment required from secondary care providers and commissioners with the benefits that accrue being shared between the stakeholders.6,7

In November 2015, a gain-share was agreed between University Hospital Southampton (UHS) NHS Foundation Trust and our local Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs) to commission a managed switching programme to support the change of patients already established on Remicade® to biosimilar infliximab as well as increase the capacity of the clinical IBD service. In late 2014, we developed a business case modelled on 150 IBD patients treated with a mean of 400mg Remicade® every eight weeks for one year with a range of savings in drug acquisition costs. This showed a potential saving of up to £812,000 per annum with a 50% discount in drug costs if all patients agreed to change to biosimilar infliximab.

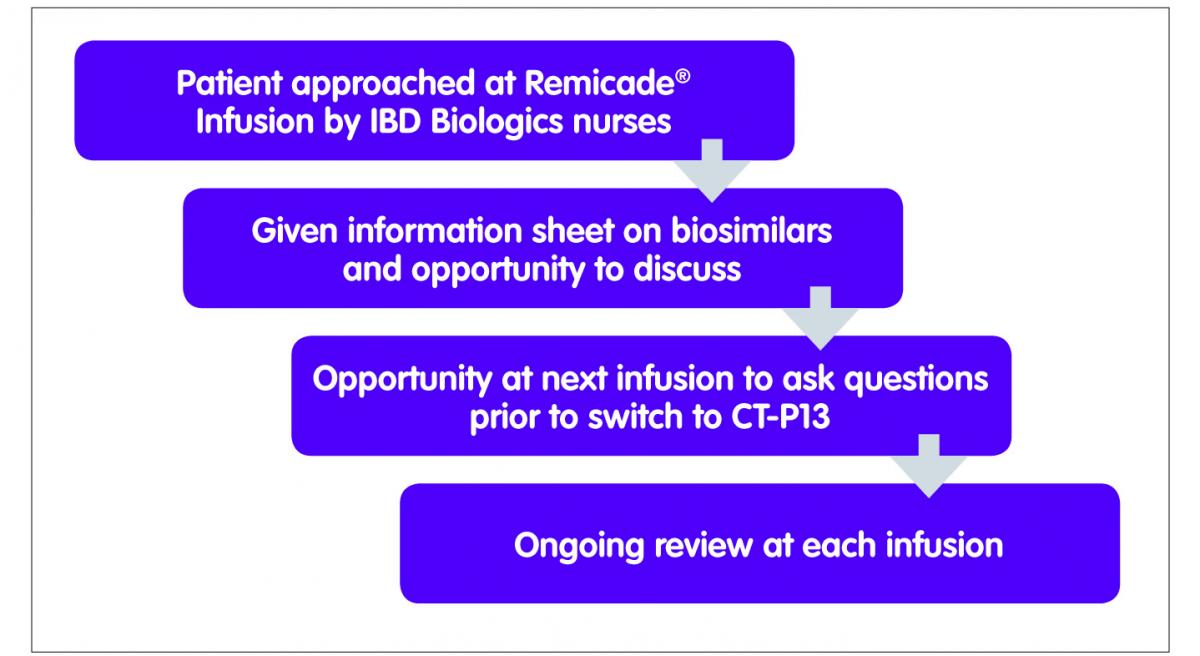

One of the challenges facing IBD clinicians was the lack of published data in IBD. We developed a managed switching programme with support from all key stakeholders including our local IBD patient panel, gastroenterologists, pharmacists and the IBD nursing team to not only support patients through this process but also to include a risk management plan (Figure 1). The proposed switching programme was discussed in detail with the IBD patient panel as well as with patients in clinic on an ad hoc basis. Many patients on the panel were on infliximab or other biological medicines and therefore able to offer insight from the patient perspective. Patient feedback suggested that the trust in the clinicians providing the service and the re-assurance of no harm was crucial in this process, as well as easy access to their clinical team in event of an adverse event. The patient panel agreed that the additional clinical monitoring and surveillance provisions included in the programme, including being seen by the IBD nurse specialist at all infusions, would satisfy their concerns. A major motivation for patients was seeing at least some of the cost savings being reinvested in improvements to their care, in particular in dietetics services.

Gastroenterologists responsible for the care of the patients raised a number of concerns. These were addressed by in depth discussions with the IBD clinical lead around the basic science, regulatory processes and clinical outcomes in other disease areas. They also saw the risk management plan, robust pharmacovigilance procedures and the prevention of interchangeability as being critical to the safe switching of patients.

Figure 1: Managed switching programme

A three-year business case to support the managed switching programme, as well as investment in the improvement of the IBD service, was agreed and supported by a gain-share agreement with the lead specialist pharmacists for commissioning in the two local CCGs. A full time IBD nurse was recruited to increase the capacity of the nurse-led IBD biologics service as well as develop an in-patient IBD nursing service. A 0.5 WTE administrator was recruited to support the service, a 0.2 WTE biologics pharmacist and an increase in dietetics resources. The business case amounted to £103,000, or approximately 12% of the projected savings.

Prior to switching to biosimilar infliximab, patients were asked to complete a questionnaire at each infusion. This included the IBD control PROM, disease activity scoring and a questionnaire on side effects. Serum was collected to measure anti-TNF drug activity before and after the switch. It is expected that this data will show any significant differences between the originator infliximab and the biosimilar at an early stage by the regular data review by the IBD team as part of a risk management strategy. The biologics pharmacist changed electronic prescribing system to ensure infliximab prescribing by brand name to reduce any risk of interchangeability between Remicade® and Inflectra®.

The switching programme started in April 2015. Patients having Remicade® were approached by the IBD specialist nurses at the time of their infusions, and after discussions focused on switching, were also given a letter advising them that their medicine was being switched from Remicade® to Inflectra®. At the next infusion, it was confirmed that they had no further questions or concerns and that they consented to the switch. The team have identified good communication with patients as well as trust in the IBD team as being critical to the successful implementation of the switch programme.

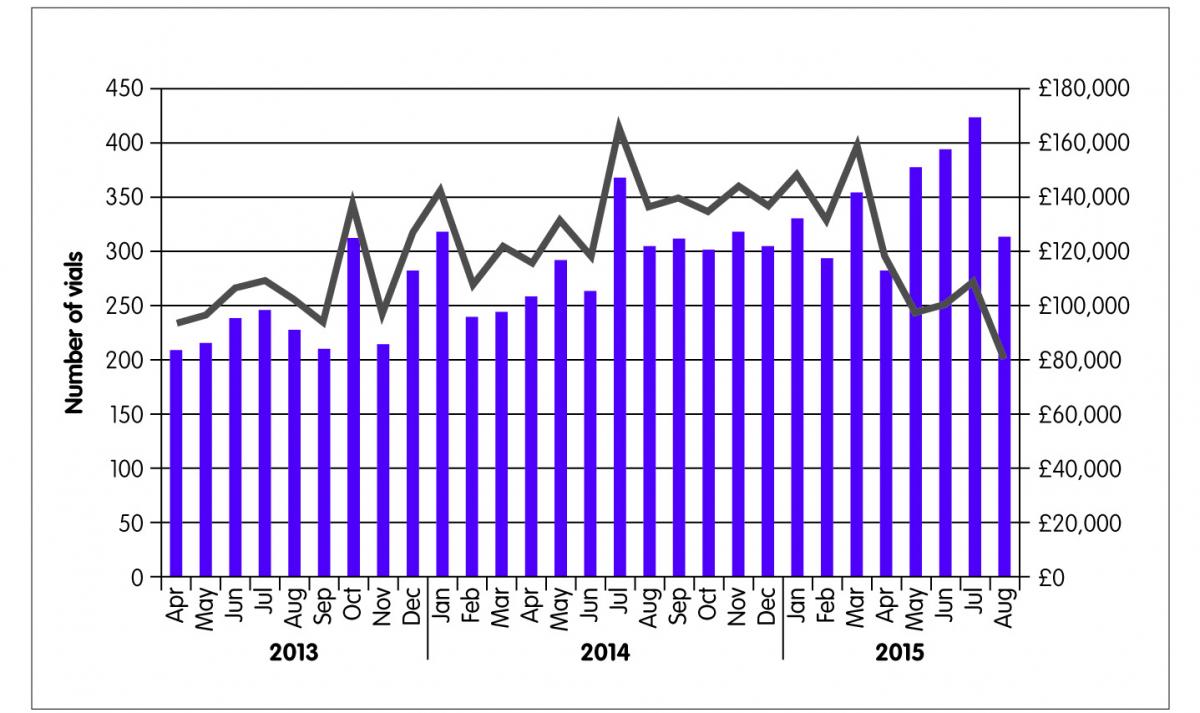

After two months, 134 patients were switched from Remicade® to the biosimilar Inflectra®. They continue to be monitored and, to date only two patients have requested a review of the switch on medical grounds. Understandably some patients with severe disease required more detailed discussions and reassurance before agreeing to the switch. These people have had a full assessment and review in line with local protocols and are monitored on a case-by-case basis. Figure 2 shows the numbers of vials of infliximab dispensed by the pharmacy and the drug acquisition costs billed to the CCG. It is estimated that £293,000 were saved in the first four months of the switching programme.

Figure 2: Cost savings

Conclusions

To summarise, the gain-share model of a switch to biosimilar infliximab has proven to be effective and has the potential to achieve large cost savings providing that there remains a focus on patient’ needs and investment in local IBD biologics services, including staff (in our case, IBD nurses, clerical support and pharmacists) and IT (such as the UK IBD registry patient management system). These savings can only be achieved with close collaboration, transparency and trust between patients, clinicians, hospital management and care commissioners, with all stakeholders being appropriately incentivised to deliver high quality, cost effective patient care. Gain-share provides an effective framework for the introduction of other biosimilars such as adalimumab in the future.

Key points

- The switch from Remicade® to infliximab biosimilars in the inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) population in University Hospital Southampton achieved substantial initial cost savings approximating to £300,000 without adverse affects to patient care.

- Gain-share agreement is an effective way of ensuring that cost savings of the biosimilar switching programme are distributed equally between the IBD service providers and commissioners.

- Cost savings generated by switching to infliximab biosimilars can be successfully reinvested in the local IBD biologics services including nursing, clerical and pharmacy staff and information technologies.

- High quality care and outcomes for the IBD patients undergoing a swith to biosimilar infliximab can be maintained by good communication and robust risk management planning.

- Gain-share agreement has the potential for wider adoption in other IBD units across the National Health Service as well as other healthcare systems.

References

- GlobalData. Top 50 pharmaceutical products by global sales PMLiVE.com: PMGroup; 2015. www.pmlive.com/top_pharma_list/Top_50_pharmaceutical_products_by_global_sales. (Accessed 14 December 2015).

- European Medicines Agency. Inflectra authorisation details, 2013. www.ema.europa.eu/ema/index.jsp?curl=pages/medicines/human/medicines/002778/human_med_001677.jsp&mid=WC0b01ac058001d124. (Accessed 14 December 2015).

- European Medicines Agency. Remsima authorisation details, 2013. www.ema.europa.eu/ema/index.jsp?curl=pages/medicines/human/medicines/002576/human_med_001682.jsp&mid=WC0b01ac058001d124. (Accessed 14 December 2015).

- Yoo DH et al. A randomised, double-blind, parallel-group study to demonstrate equivalence in efficacy and safety of CT-P13 compared with innovator infliximab when coadministered with methotrexate in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis: the PLANETRA study. Ann Rheum Dis 2013;72(10):1613–20.

- Park W et al. A randomised, double-blind, multicentre, parallel-group, prospective study,comparing the pharmacokinetics, safety, and efficacy of CT-P13 and innovator infliximab in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: the PLANETAS study. Ann Rheum Dis 2013;72(10):1605–12.

- NHS England. Principles for sharing the benefits associated with more efficient use of medicines not reimbursed through national prices. Medical Directorate; 2014. www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/princ-shar-benefits.pdf. (Accessed 14 December 2015).

- Howard C. Achieving savings from high cost drugs, Department of Health; 2012. www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/213111/high-cost-drugs.pdf. (Accessed 14 December 2015).