Administration of antibiotics together with probiotics can reduce the risk of developing antibiotic-associated diarrhoea and Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhoea

Alejandro Palacios PhD BSc P2P DipABPI

Medical Science Liaison,

Protexin Human Healthcare, UK

Administration of antibiotics together with probiotics can reduce the risk of developing antibiotic-associated diarrhoea and Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhoea

Alejandro Palacios PhD BSc P2P DipABPI

Medical Science Liaison,

Protexin Human Healthcare, UK

Since the discovery of antibiotics, these once called “miracle drugs” have saved millions of lives. However, after nearly seven decades of use, antibiotics are in a well-acknowledged crisis because of the development of antibiotic resistance. Antibiotics are one of the most prescribed drugs in the world. Their extensive use and, more importantly, their improper use, together with the reduced number of new antibiotics in the pharmaceutical drug development pipeline, in particular those with new modes of action, are making the battle against bacterial diseases harder to win. Even though antibiotics are very effective in the treatment of many different bacterial diseases, sometimes their remarkable antibacterial power and broad target specificity can cause adverse effects like acute bacterial diarrhoea and oral and vaginal yeast infections. Diarrhoea is a common side effect of antibiotic treatment that, in addition to be distressing and unpleasant, can lead to dehydration, electrolyte imbalance and hypotension, which, in some cases can be life-threatening.

Antibiotic-associated diarrhoea and Clostridium difficile infection

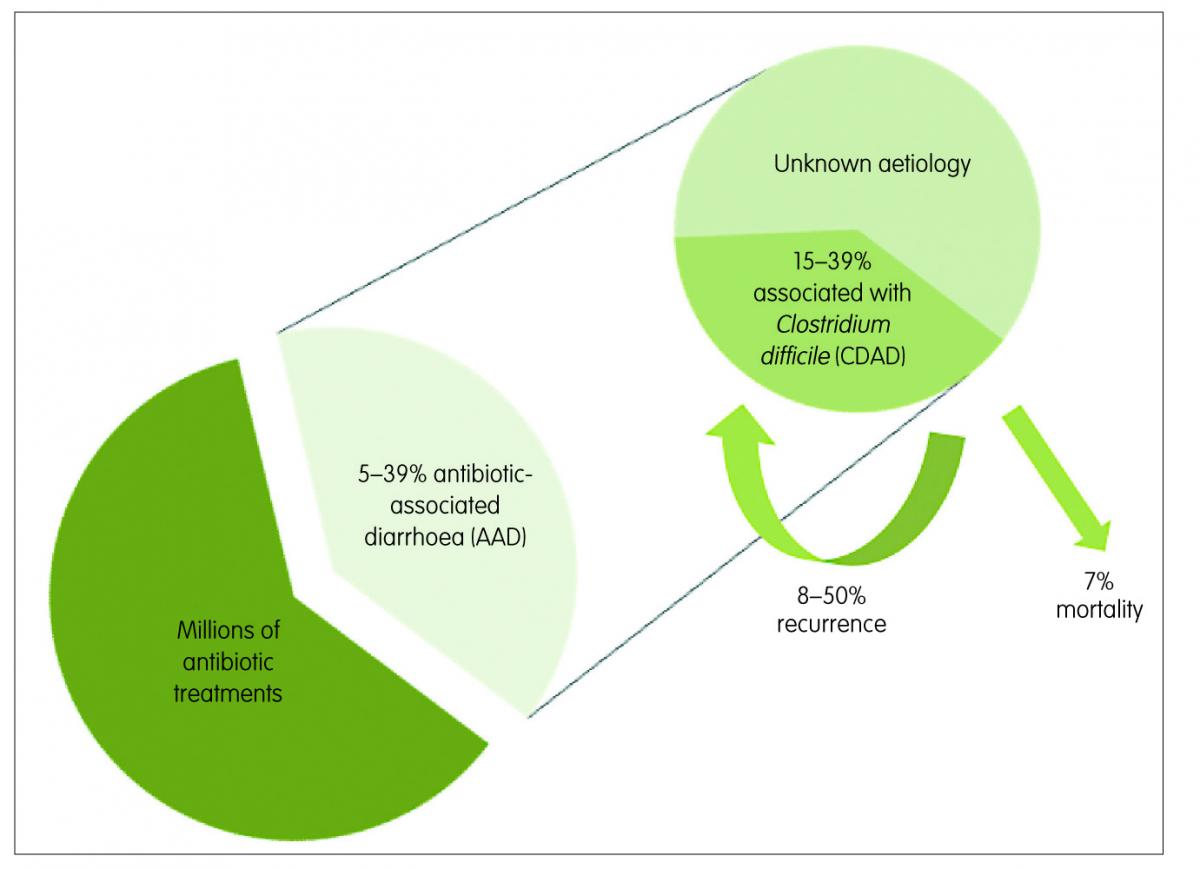

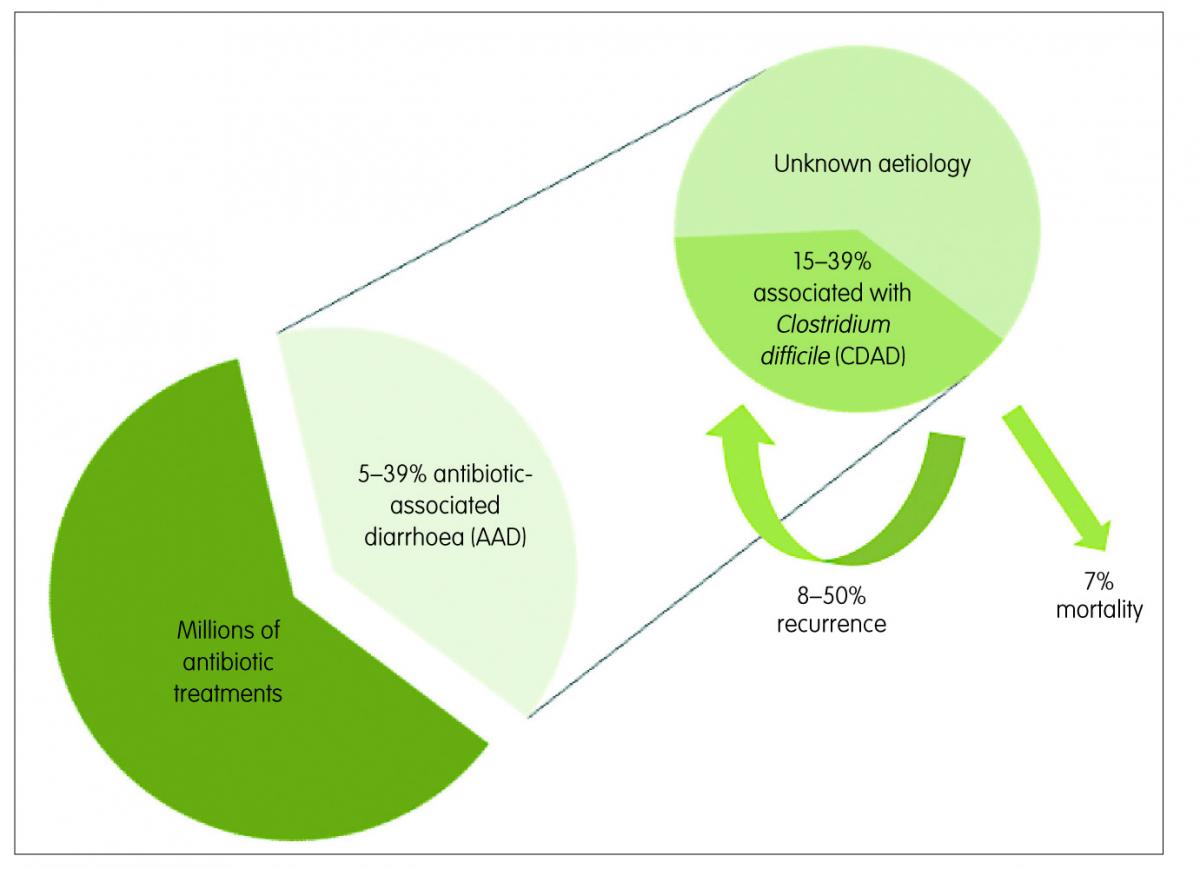

Antibiotic-associated diarrhoea (AAD) is the most common intestinal complication following antibiotic use, especially for broad-spectrum antibiotics. AAD generally encompasses people exposed to antibiotics who develop, in the absence of other causes, diarrhoea within eight weeks of treatment. Its rate of occurrence varies among reports, with a range of 5–39%, depending on the population and the type of antibiotic.1

This medical complication can range in severity from mild diarrhoea to life-threatening pseudomembranous colitis. Infection with Clostridium difficile (C. difficile) can be the cause in 15–39% of the AAD cases,2 while in most of the remaining cases the aetiology is unknown. The rate of recurrence of C. difficile-associated diarrhoea (CDAD) ranges from 8–50% in patients over 65 years3 and infection with this spore-forming bacteria is associated with most of the severe cases of AAD. When present, it can be fatal in nearly 7% of cases (Figure 1).4

Antibiotics can target specific bacterial components and metabolic pathways that are often shared by a wide range of bacterial types. For this reason, when a person takes antibiotics, it is very likely that these antimicrobial drugs will also kill part of the patient’s normal microbiota, resulting in a microbial imbalance or dysbiosis.5 When patients undergo an antibiotic treatment, part of their guts’ symbiotic bacteria are killed and, as a consequence of that, the structure of their pre-existing microbial community is significantly changed. Recent gut metagenomic and metabolomic studies have generated enough experimental evidence to support the idea that changes in the structure and composition of the gut microbial community caused by antibiotics can put an individual at risk of developing infections from opportunistic pathogens, such as C. difficile.6,7 Another demonstration of the important connection between gut microbial imbalance and C. difficile infection is that the use of gastric acid suppressing drugs, like proton pump inhibitors, known to remarkably alter the composition of the gut microbiota, also significantly increases the incidence of CDAD.7

Figure 1: Antibiotic-associated diarrhoea (AAD) and Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhoea (CDAD)

The role of probiotics in the prevention of AAD and CDAD

A substantial number of randomised clinical trials have now addressed the prevention of the development of AAD and CDAD using probiotic bacterial cultures. In fact, some of the most recent clinical trials data meta-analyses have shown that probiotics can reduce the relative risk of AAD by 42% (RR 0.58; 95% CI, 0.50 to 0.68; p<0.001),8 and by 64% (RR 0.36; 95% CI 0.26 to 0.51; p<0.0001) in the case of CDAD.9 The results of these rigorous systematic reviews and meta-analyses are helping more scientists and clinicians to realise that there is sufficient evidence to conclude that administration of high-quality probiotic bacteria, as an adjunct to antibiotic treatment, is associated with a reduced risk of developing these debilitating and potentially life-threatening conditions. It is worthwhile mentioning that not all tested probiotic preparations have demonstrated to be effective in reducing the risk of AAD, as shown in the recent PLACIDE clinical trial conducted in the UK.10 However, given the nature of strain-specific properties of probiotics, it is possible that the bacterial strains used in some unsuccessful studies do not have the necessary characteristics to prevent the development of AAD. In fact, recent studies using animal models strongly suggest that individual bacterial species do not drive alone the colonisation resistance to C. difficile11 and that multi-strain probiotic preparations are more likely to be effective in the prevention of AAD and CDAD than those including one or a couple bacterial strains.12 It is important to take into consideration that, commercially available probiotics have different bacterial strains, counts, presentations and manufacturing techniques. For this reason, the choice of the probiotic product needs to be made on the grounds of the scientific and clinical information available for each individual product and formulation.

Prevention of AAD and CDAD with the use of probiotics has also proven to be cost-effective, as CDAD cases are estimated to increase their hospital stay on average by 21 days,13 together with all the associated care costs. Even in places like England, where the establishment mandatory surveillance and other control measures on antibiotic prescription and hygiene protocols have led to a reduction, from 2007 to 2014, of 74% in the cases of C. difficile infection, only in 2014 there were nearly 14,000 cases,14 with healthcare costs from £4300 per case.15

Antibiotic resistance

There are important worldwide concerns about the over-prescription of antibiotics, as this may lead to increased microbial resistance to these medicines. Development of antibiotics resistance poses a significant public health threat, especially since antibiotics are widely used in medical practice in both primary and secondary care. For example, in England alone during 2013, the National Health Service (NHS) dispensed more than 41 million prescriptions of antibacterial drugs.16

Antibiotic resistance threatens the effective prevention and treatment of diseases that, under different circumstances, would have been easier to treat. Multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB) and infections with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) are examples of diseases of current significant concern because they are more difficult to treat, due to the development of antibiotic-resistant strains. These paramount public health problems have important economic consequences and have already claimed many lives.

To prevent the development of bacterial resistance, it is fundamental that antibiotics are always prescribed according to the principles of antimicrobial stewardship. This means, prescribing them only when they are needed, promoting the selection of optimal antimicrobial drug regimes, dose, duration of therapy, and route of administration.

It is well known that antibiotics do not fight infections caused by viruses like colds, flu and most sore throats and bronchitis. However, it is common that patients with these conditions expect and often request their general practitioners to prescribe them antibiotics. The patient’s belief about the effectiveness of antibiotics against common respiratory tract infections puts pressure on doctors to over-prescribe.17 In addition to the problem of over-prescription of antibiotics, patient’s failure to complete their course of antibiotic treatment also plays an important role in the development of antibiotic resistance. When an antibiotic treatment is interrupted, it creates the selective pressure of sub-lethal dosages for pathogens to adapt and evolve into antibiotic-resistant strains. However, it is important to note that some patients do not only stop their antibiotic treatment when they feel better. Antibiotic-associated adverse events like allergy, secondary infections and diarrhoea can also prompt patients and clinicians to interrupt treatment.

Upon the development of AAD, it is, in many countries like in the UK, standard clinical practice to interrupt any antibiotic treatment associated with this complication, if considered clinically appropriate. This standard of best practice has as a main objective to control the severity of the diarrhoea by allowing normal intestinal microbiota to be re-established. If the diarrhoea is confirmed to be associated with C. difficile, a suitable second round of antibiotics is normally prescribed. This intervention leads, in many cases, to an effective limitation of the patient’s diarrhoeal symptoms and their associated risks. However, stopping the first round of antibiotics aimed at treatment of pre-existing underlying medical conditions, might on the other hand give rise to ecological conditions for the selection of antibiotic-resistant strains of the bacteria that caused the first course of antibiotics to be administered. One example of this situation could be the development of beta-lactam and/or macrolide-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae strains during the incomplete treatment of an acute lower respiratory tract infection.

The role of probiotics in the prevention of antibiotic resistance

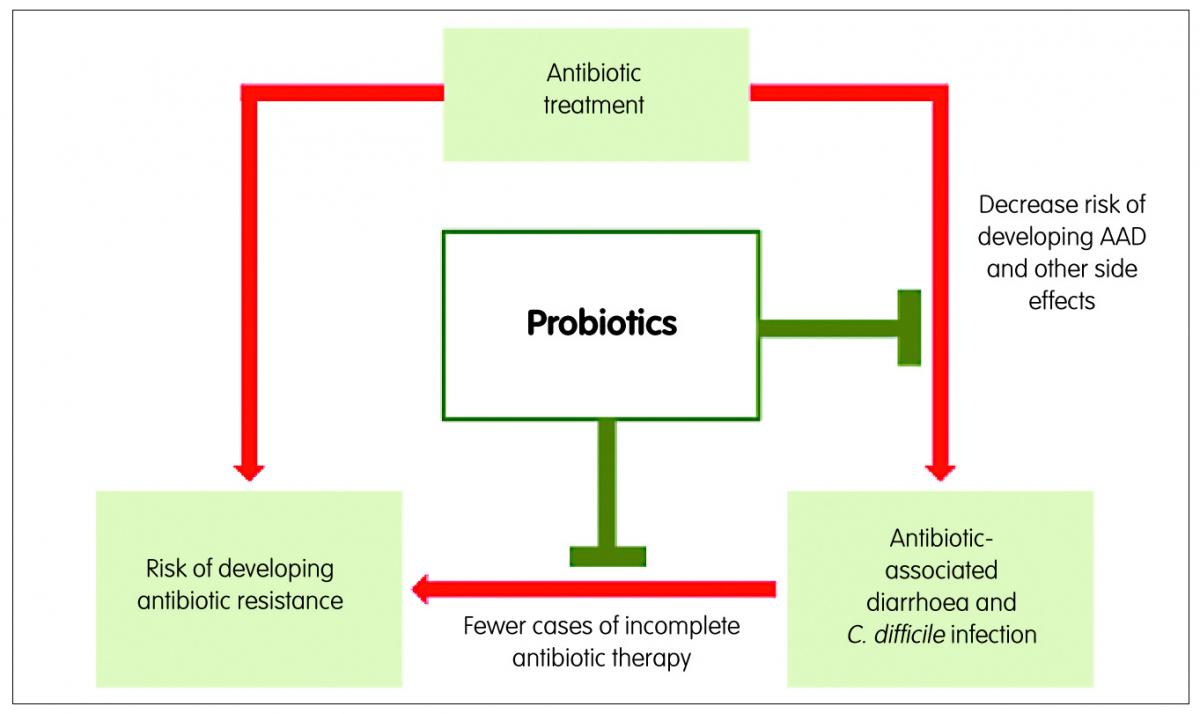

From an economic perspective, providing patients with probiotics together with antibiotics has been shown to imply considerable cost savings, because of the reduction of the occurrence of AAD and CDAD and their associated longer hospital stays and treatment costs.4 Additionally, a general practice of prescription of antibiotics together with probiotics for antibacterial medical treatments would, by preventing AAD and CDAD, decrease the number of times antibiotics treatments from underlying medical conditions need to be interrupted, decrease the number of treatments to combat C. difficile infection and, as a consequence, decrease the risk of occurrence of antibiotic resistance. The administration of probiotics together with antibiotics can also reduce other antibiotic-associated side effects, such as nausea and abdominal pain,18 which in turn improves treatment compliance and reduces the risk of sub-optimal antibiotic dosing and reduces the risk of developing resistant bacterial strains (Figure 2). Probiotics can also improve the efficacy of the initial antibiotic treatment, thereby reducing the need for repeat prescriptions. A good example is the significant improvement on Helicobacter pylori eradication when probiotics are given in addition to the standard triple therapy of two antibiotics and a gastric acid-suppressing drug.19

Figure 2: Role of probiotics in the prevention of antibiotic-associated diarrhoea and antibiotic resistance

Conclusion

Clinical and basic research have shown that administration of antibiotics together with high-quality multi-strain probiotic preparations represent a great opportunity for the healthcare sector to reduce the burden of AAD and C. difficile infection, and would contribute to the reduction of the development of problematic antibiotic resistance.

Key points

- After nearly seven decades of use, antibiotics are in a well-acknowledged crisis because of the development of antibiotic resistance.

- Antibiotic-associated diarrhoea (AAD) is the most common intestinal complication following antibiotic use, especially for broad-spectrum antibiotics.

- Clostridium difficile is one of the most important causative agents of AAD in hospitals in elderly patients.

- Taking of antibiotics together with probiotics can reduce the risk of developing AAD and Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhoea (CDAD).

- Prevention of AAD and CDAD with the use of probiotics has also proven to be cost-effective, significantly reducing the costs associated with longer hospital stays notable of hospital-associated infections.

References

- McFarland LV. Epidemiology, risk factors and treatments for antibiotic-associated diarrhea. Dig Dis 1998;16:292–307.

- Viswanathan VK, Mallozzi MJ, Vedantam G. Clostridium difficile infection: An overview of the disease and its pathogenesis, epidemiology and interventions. Gut Microbes 2010;1:234–42.

- Louie TJ et al. Effect of age on treatment outcomes in Clostridium difficile infection. J Am Geriatr Soc 2013;61:222–30.

- Lenoir-Wijnkoop I et al. Nutrition economic evaluation of a probiotic in the prevention of antibiotic-associated diarrhea. Front Pharmacol 2014;5:13.

- Preidis GA, Versalovic J. Targeting the human microbiome with antibiotics, probiotics, and prebiotics: gastroenterology enters the metagenomics era. Gastroenterology 2009;136:2015–31.

- Theriot CM, Young VB. Microbial and metabolic interactions between the gastrointestinal tract and Clostridium difficile infection. Gut Microbes 2014;5:86–95.

- Janarthanan S et al. Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea and proton pump inhibitor therapy: a meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol 2012;107:1001–10.

- Hempel S et al. Probiotics for the prevention and treatment of antibiotic-associated diarrhea: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2012;307:1959–69.

- Goldenberg JZ et al. Probiotics for the prevention of Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea in adults and children. Cochrane database Syst Rev 2013;5:CD006095.

- Allen SJ et al. Lactobacilli and bifidobacteria in the prevention of antibiotic-associated diarrhoea and Clostridium difficile diarrhoea in older inpatients (PLACIDE): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre trial. Lancet 2013;382:1249–57.

- Lawley TD, Walker AW. Intestinal colonization resistance. Immunology 2013;138:1–11.

- Chapman CMC, Gibson GR, Rowland I. In vitro evaluation of single- and multi-strain probiotics: Inter-species inhibition between probiotic strains, and inhibition of pathogens. Anaerobe 2012;18:405–13.

- Wilcox MH et al. Financial burden of hospital-acquired Clostridium difficile infection. J Hosp Infect 1996;34:23–30.

- Public Health England. Clostridium difficile infections: quarterly counts by acute trust and CCG and financial year counts and rates by acute trust and CCG up to financial year 2014 to 2015. 2015. Available at www.gov.uk/government/statistics/clostridium-difficile-infection-annual-data. (Accessed 11 November 2015).

- National Audit Office. Reducing Healthcare Associated Infections in Hospitals in England. Natl. Audit Off. 2009. Available at www.nao.org.uk/report/reducing-healthcare-associated-infections-in-hospitals-in-england/. (Accessed 11 November 2015).

- Health and Social Care Information Centre. Prescription cost analysis – England 2013. HSCIC. 2013. Available at www.hscic.gov.uk/catalogue/PUB13887. (Accessed 11 November 2015).

- McNulty CAM et al. Expectations for consultations and antibiotics for respiratory tract infection in primary care: the RTI clinical iceberg. Br J Gen Pract 2013;63:e429–36.

- Ouwehand AC et al. Probiotics reduce symptoms of antibiotic use in a hospital setting: a randomized dose response study. Vaccine 2014;32:458–63.

- Gong Y, Li Y, Sun Q. Probiotics improve efficacy and tolerability of triple therapy to eradicate Helicobacter pylori: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Int J Clin Exp Med 2015;8:6530–43.