Kidney cancer follows distinct evolutionary paths, scientists have discovered. Their findings will enable them to detect whether a tumour will be aggressive, and also reveal that the first seeds of kidney cancer are sown as early as childhood.

Kidney cancer follows distinct evolutionary paths, scientists have discovered. Their findings will enable them to detect whether a tumour will be aggressive, and also reveal that the first seeds of kidney cancer are sown as early as childhood.

The three Cancer Research UK funded studies, published in the journal Cell, shed light on the fundamental principles of cancer evolution and could lead to future clinical tests to give patients more accurate prognoses and personalised treatment, researchers said.

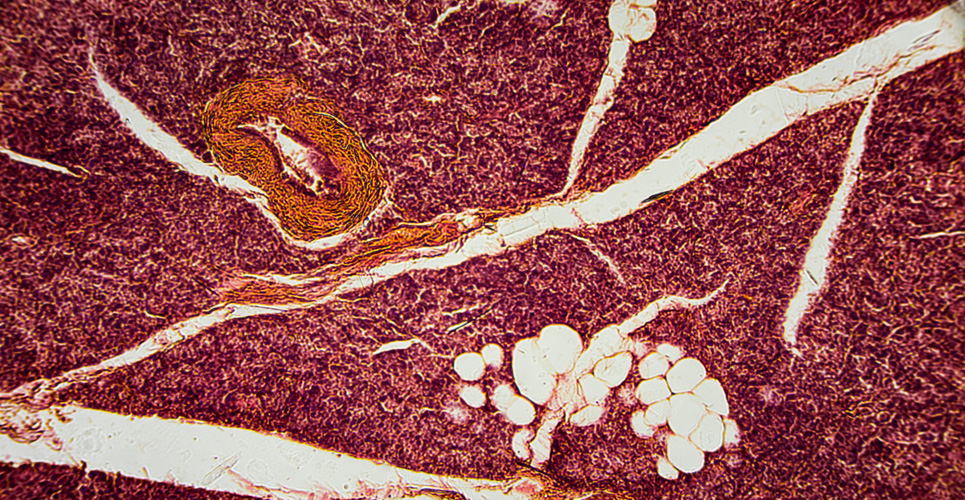

In the first two papers, the TRACERx Renal team, based at the Francis Crick Institute, UCL, The Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust, and Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust, analysed over 1,000 tumour samples from 100 kidney cancer patients to reconstruct the sequence of genetic events that led to the cancer in each patient.

Their analysis reveals that there are three evolutionarily distinct types of kidney cancer. The first type follows a slow evolutionary path, never acquiring the ability to become aggressive.

The second type forms the most aggressive tumours, which evolve through a rapid burst of genomic damage – including changes that affect large chunks of the genome – early on in the cancer’s development. This gives the tumour all it needs to spread to many other parts of the body, often before the primary cancer is diagnosed, researchers discovered.

The third tumour type acquires the ability to spread through a gradual accumulation of genomic damage. They typically spread over a longer period of time, often to just one site. These tumours are composed of many different populations of cancer cells, some of which are aggressive.

The researchers confirmed their findings by analysing tumour samples obtained after death from patients in the post-mortem tumour sampling study, PEACE.

Commenting on the findings, lead author Dr Samra Turajlic, Cancer Research UK clinician scientist, the Francis Crick Institute, and consultant oncologist at The Royal Marsden said: “The outcomes of patients diagnosed with kidney cancer vary a great deal – we show for the first time that these differences are rooted in the distinct way that their cancers evolve.

“Knowing the next step in cancer’s evolutionary trajectory could tailor the treatment choice for individual patients in the next decade. For instance, patients with the least aggressive tumours could be spared surgery and monitored instead, and those with gradually evolving tumours could have the primary tumour surgically removed even after it has spread.”

The researchers also analysed the traits that distinguish cells in the primary tumour that lead to secondary tumours, from those that never leave the primary tumour site. The cells that could spread were distinguished by changes at the chromosome level rather than mutations in genes.

Two specific chromosome changes that drive metastatic spread were found that could serve as a useful marker to identify patients that are at risk of metastatic disease, researchers found.

The study’s corresponding author Professor Charles Swanton, group leader at the Francis Crick Institute and UCL, and Cancer Research UK’s chief clinician, said the study showed thatt “large changes in the genome appear to be a particularly high risk factor for early progression and death following surgery.

“We hope that in the future this work will help tailor surgical and medical intervention to the right patients at the right time.”

The third paper in this TRACERx Renal study, which was co-led by researchers at the Wellcome Sanger Institute in Cambridge, analysed the earliest events that trigger kidney cancer development. It shows they can take place in childhood or adolescence, up to 50 years before the primary tumour is diagnosed.

The findings offer an opportunity for monitoring and early intervention in the treatment of kidney cancer, particularly in high-risk groups, such as those with an inherited risk of developing the disease.

Sir Harpal Kumar, Cancer Research UK’s chief executive, said: “When Cancer Research UK scientists first revealed that the genetic makeup of cancers evolves over time, helping tumours to become resistant to treatments, we were faced with a monumental challenge of how to tackle this complexity.

“Now we know that there are rules in this complexity, and we could use these rules to help choose the best treatments, and potentially to diagnose some cancers much earlier.”

Sources

- Mitchell. T. et al Timing the landmark events in the evolution of clear cell renal cell cancer: TRACERx Renal Cell (2018)

- Turajlic, S. et al Deterministic evolutionary trajectories influence primary tumour growth: the TRACERx Renal study Cell (2018)

- Turajlic, S. et al Tracking renal cancer evolution reveals constrained routes to metastases, results from the TRACERx Renal study Cell (2018)