Becki Davies

MSc

Editor, HPE

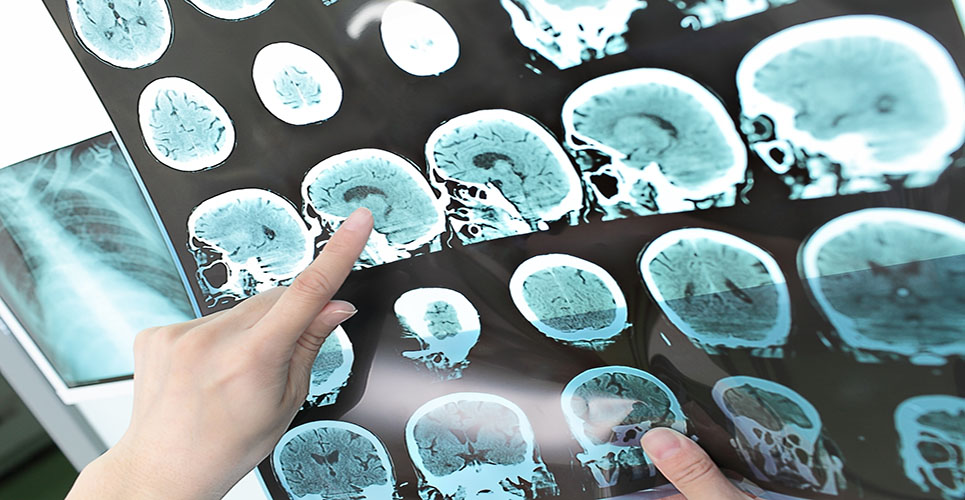

In Europe, approximately one person in 900 suffers from multiple sclerosis (MS), a disorder in which demyelination of the neuronal axons produces a range of symptoms dependent on the part of the nervous system affected. Common symptoms include visual disturbance, problems with balance and coordination, spasticity, altered sensation, abnormal speech, fatigue (one of the most common and troubling symptoms of MS), bladder and bowel problems, problems with sexuality and intimacy, and cognitive and emotional disturbances. Nearly half of those affected don’t experience severe symptoms and are able to lead normal and productive lives, while 40% go on to develop progressive MS after living with the relapsing-remitting form of the disease for a number of years. At least 15% of people with MS eventually become severely disabled, requiring a wheelchair on a fulltime basis.

Women are 50% more likely to develop MS than men, with onset usually occurring between the ages of 29 and 33 years, although the range of onset is much broader – anything from 10 to 59 years.

Carolina first developed symptoms at the age of 14, with pins-and-needles sensations in her arms. A few years later, at the age of 19, she developed double vision, prompting her concerned parents to take her to see a neurologist in her home country of Italy. We asked her about her experience of multiple sclerosis.

When were you first diagnosed with MS?

“My parents didn’t initially tell me that the neurologists suspected MS, they just said that I had a problem with my myelin. Apparently, after visiting someone with MS, I told my mother that I would rather be dead than suffer from it, so she was afraid to tell me.” It wasn’t until after her marriage that Carolina had to confront the truth; when she went to Israel to take part in clinical trials for glatiramer acetate the doctor there told her that the myelin disorder she was suffering from was actually MS.

What medications have you taken?

“I moved to the UK with my husband, and continued to take glatiramer for about 10 years, first during the clinical trials and then via my neurologist in Italy when it became available to people with MS there. During this time I was experiencing perhaps one mild relapse a year and the disease remained stable. My neurologist eventually decided to start me on interferon beta instead. It meant I had injections every other day, rather than daily. However, side-effects meant that the day after the infection I would feel very unwell, and my symptoms weren’t well controlled.”

It was at this time, three years ago, that Carolina’s symptoms worsened and she developed secondary progressive MS. “Now I have difficulty in walking, and in fact cannot walk at all without using a stick.” She moved back to glatiramer after six months of taking interferon beta, but this no longer seemed to control her symptoms effectively.

For the last nine months, Carolina has been receiving the chemotherapy drug mitoxantrone, which is administered by a drip, requiring a visit to hospital in Italy once every three months. “I now have a lot more stamina. It is quite nasty being on a chemotherapy drug, but I haven’t lost my hair. I do have to be careful about where I go, and who I see, because I don’t want to catch an infection, but so far I have been very lucky.” Carolina joined the waiting list for physiotherapy some time ago, on the recommendation of her UK neurologist, but has no idea when this is likely to start.

What differences have you noticed between MS management in Italy and the UK?

Living in the UK and receiving treatment in Italy has given Carolina insight into the differences between MS care in the two countries. “I feel very lucky that my doctor in Italy can give me any drug that becomes available for MS free of charge while my friends here in the UK don’t have that opportunity, although I do have a friend in the UK who is now receiving glatiramer funded through the risk-sharing scheme.”

Carolina says that her neurologist in Italy has been very helpful in explaining about her treatment. “My neurologist in the UK is very helpful, but it is often difficult to get hold of her as she is very busy. In Italy I attend a special neurology hospital, where doctors have more time for individual patients – I can even phone them from the UK if I have a question about my treatment.”

Although it has been easier to access drug treatment in Italy, Carolina has found the support systems for those with MS to be much better in the UK. “I attended a series of sessions here which discussed the psychological impact of living with the condition, and coping strategies for everyday life, something which I haven’t come across in Italy.”

Providing support

Although lifespan is not significantly affected in those with MS, quality of life may be significantly so. MS is ultimately a diagnosis of exclusion, with the rate of misdiagnosis being 5–10%; this fact, coupled with the highly variable prognosis, means that patients may be living with a significant degree of uncertainty about what the future holds. Support groups can offer advice on matters such as how to tell family and colleagues, and can put patients in touch with others with MS so they don’t have to feel isolated.

We would like to thank Carolina Davis and the MSIF for their help with this article.

Events

European MS Platform Annual Congress

Malta

1–4 May 2003

W:www.ms-in-europe.org

13th Meeting of the European Neurological Society

Istanbul, Turkey

14–18 June 2003

W:www.ensinfo.com

6th International Brain Research Organisation World Congress of Neuroscience

Prague

Czech Republic

10–15 July 2003

W:www.ibro2003.cz

Multiple Sclerosis International Federation

2003 International Conference

Berlin, Germany

20–24 September 2003

W:www.msif.org