Due to the high-risk nature of insulin, a switch to a biosimilar needs to be performed in a cautious and facilitated manner, and pharmacists should be empowered to support this within their level of competence.

Biosimilar insulins are biological copies of original parent insulins. Due to the complex structure of biologic medicines, it is almost impossible to completely replicate the original reference module in the manufacturing process.

Generic drugs have simple primary structures and so can be easily replicated. Biosimilar medicines, by contrast, might have small differences to the structure of the originator molecule when produced. The molecules do however have to be comparable and in order to gain European Medicines Agency (EMA) approval, demonstration of bioequivalence is essential.1

This is achieved through comprehensive comparability studies to show that there are no clinically meaningful differences in terms of efficacy, quality and safety.2

Biosimilar medicines have already been utilised across the National Health Service (NHS) in areas such as rheumatology and oncology.2 Biosimilars have advantages as they are often cheaper than the originator medicine because they do not have the associated production costs and they introduce competition within the market.

Where have they been used?

Other clinical specialities, such as rheumatology, have successfully introduced biosimilar switches for products. Mid Yorkshire Hospitals NHS Trust2 was able to achieve an 85% uptake of biosimilar infliximab and etanercept through the use of a pharmacy-led switching programme. This Trust highlighted to service users the potential cost savings and how these could be used to re-invest in wider services, such as funding for specialist nurses and other novel therapies. Just as in this case, it is known that service users are likely to be receptive to biosimilar medicines if they are self-funding therapy or if they perceive they are helping the NHS save money.3 Due to the high risk and variable nature of insulins, biosimilars should never be introduced as part of a whole-population switch.

What does NICE say?

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) currently has no detailed guidance on the initiation and management of biosimilar insulin use in practice. A key therapeutic topic has been published on biosimilar medicines in general and summarises key points.4 Of note, it recommends developing and agreeing local policies to support managed introduction of biosimilar switches. Such programmes have proved successful in other fields such as rheumatology. As insulin is a high-risk medicine and subject to a larger degree of in-patient variability of response, blanket switch programmes would not be recommended.

NICE guidance for the use of human growth hormone in paediatric patients, for which there is a variety of biosimilar products, states: ‘The choice of product should be made on an individual basis after informed discussion between the responsible clinician and the patient and/ or their carer about the advantages and disadvantages of the products available, taking into consideration therapeutic need and the likelihood of adherence to treatment. If, after that discussion, more than one product is suitable, the least costly product should be chosen.5 This is certainly becoming more relevant as the insulin biosimilar market grows.

What current guidance is there?

Diabetes UK has released a position statement regarding biosimilar insulin. This gives recommendations for healthcare professionals, people living with diabetes, commissioners and the pharmaceutical industry. Their position on people who are considered stable on their therapy is that ‘individuals well managed on an existing insulin should not be changed to a biosimilar insulin without good clinical reason, evidence of interchangeability and informed agreement from the person with diabetes’.7

The Association of British Diabetologists (ABCD) have also released a position statement on the use of biosimilar insulin. The key messages include the statement that people stable on current insulin therapy who are achieving Hba1c targets without episodes of hypoglycaemia should not be automatically switched to a biosimilar insulin. It also emphasises the importance of ensuring that switches to biosimilar insulin should be made by the clinical teams with the appropriate level of expertise, experience and training.8

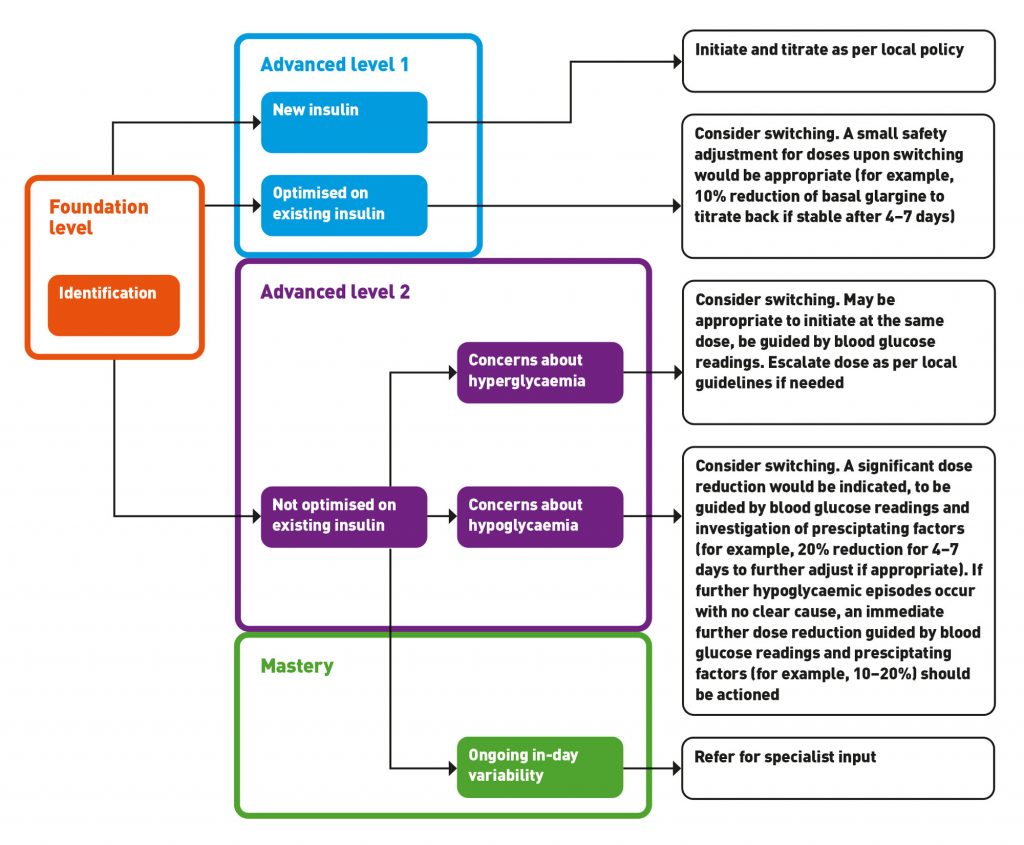

Newly published guidelines give a practical flowchart for health care professionals to use to introduce biosimilar basal insulin.6 This includes information on switching people who are optimised and stable on their current insulin as well as switching those who need optimisation.

How can pharmacists help facilitate their use in practice?

Pharmacists may have a multitude of roles to play here. Direct patient care, primary care searches, budget impact work, safety netting, IT system updates, Shared care agreements, governance and medicines information might all play important parts and pharmacists may be involved in a variety of these activities based on their competence and skill sets.

- The discussion about switching to a biosimilar insulin should be done face to face and tailored to each individual, it should ideally be done by a familiar health care professional to ensure better continuity of care. This can build on trust and allow a more open and honest conversation, optimising compliance. As pharmacist roles grow and expertise develops this may be a key role for pharmacists now and in the future.

- Opportunistic identification and searches may easily identify people eligible to switch. Efforts should be made to reduce additional resource; costs should not outweigh cost savings. Annual diabetes reviews can be utilised to facilitate this process. Although little used currently, group sessions if available could also be an option to provide this service economically. They can provide information, peer support and address concerns regarding biosimilar insulins.

- Insulin passports (paper or electronic) should always be provided and updated once an insulin regime has changed or been initiated. Pharmacists involved in care should check that people have an up to date passport at each point of contact.

- Electronic prescribing systems should be up to date and list insulin as brand names to avoid confusion and errors between care providers. Tall-man lettering can also be utilised to highlight biosimilar insulins and listing order may prompt prescribers to consider a biosimilar insulin before the originator.

- Shared care agreements could also be put in place to ensure continuity of care and give clear follow up and management plans for primary care.

- As with all new medicines, biosimilar insulins are subject to black triangle status for the first few years and as such are subject to additional monitoring requirements as defined by the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulation Agency (MHRA).9 In practice, this means that all adverse events should be reported through the Yellow Card system.

What can pharmacists do?

Competence and confidence in this area of practice needs to be encouraged. As we develop our community pharmacy services, look to progress primary care roles and cultivate integrated specialist services this is an exciting area for pharmacists to contribute to cost savings and ensure safe and effective management of people living with diabetes.

The UKCPA launched a competency framework specifically for pharmacists in the management of diabetes in 2018.10 This gives pharmacists guidance on competency requirements that can be expected of them specific to the management of diabetes. Using this framework and current guidelines published by MGP,6 we have outlined the key areas for pharmacists to focus on depending on their level of experience as summarised in Table 1.

Identification

People could be identified during their routine diabetes review or pro-actively using a search of electronic patient records.

Those who should be highlighted: People living with type 2 diabetes who are currently receiving insulin where a biosimilar is available; or people living with type 2 diabetes who need to be initiated newly on insulin where a biosimilar is available.

Caution should be taken with:

- People with complex care needs

- People who have recently changed Insulin regime (for example, it would not be recommended to make more than one biosimilar switch in a 12-month period)

- Elderly people living with type 2 diabetes.

This group of patients are likely to require specialist management. This guideline is not appropriate for type 1 diabetic patients, pregnant patients or the paediatric population.

Guidance for switching

Switching to a biosimilar insulin should be a shared decision making process between the person living with diabetes and the prescriber. Consent should be obtained and clearly documented.

Key points to emphasise:

- Rationale for the switch (the use of a patient information leaflet may help facilitate this)

- Potential cost savings for the person and the NHS as applicable

- Give the person living with diabetes an opportunity to discuss concerns.

Prior to switching obtain baseline blood glucose monitoring. This should be sufficient to allow a good analysis of blood glucose profile prior to switching (for example, fasting, pre-meal and pre-bed for seven days).

Assess glycaemic control using individualised HBa1c targets, blood glucose profiles and explore any recent episodes of hypoglycaemia (blood glucose <4mmol/l or signs/ symptoms experienced).

Some biosimilar insulin devices have slight differences in administration technique and be aware that compatibility of insulin cartridges, if used, should be checked with pen devices.

Figure 1 can be used to illustrate the suggested intervention and level of expertise needed to manage different patient groups switching to biosimilar insulin. Please note this is intended as a guide and should not replace pharmacists’ own clinical judgment. It would be recommended to use detailed guidance such as the MGP guideline6 in your clinical practice.

What follow-up care should be put in place?

- Emphasise the need to be vigilant after any change in medication

- Let the person know to contact the relevant health care professional for further advice if needed

- Provide details of the diabetes helpline (if available) or who to contact for further advice/help

- Book a follow-up appointment; the time frame will vary depending on further needs for optimisation and personal needs of the person living with diabetes

- Assess compliance and address any barriers and concerns regarding insulin therapy.

What are the potential cost benefits of switching?

The NHS England commissioning framework2 aims to achieve savings by switching a minimum of 80% of patients to a biosimilar therapy. Commissioning for Quality and Innovation targets are also in place to incentivise. As insulin biosimilar switches are not appropriate as part of a blanket switch, this makes it more difficult to achieve the response as with other biosimilars.13 However, there may be other cost savings incurred following the push to increase biosimilar use. Guidelines highlighted a cost saving of £473,000 by identifying frail people receiving twice-daily NPH insulin via district nurse, who were eligible for relaxation of Hba1c targets and could therefore be reduced to once-daily glargine biosimilar, halving the required district nurse call outs.6

Table 2 illustrates comparative prices of available biosimilar insulins in the UK.14 This highlights cost savings prior to any potential discounts and incentives that pharmaceutical companies may offer.

Authors

Emma Pearson MPharm

Hannah Beba MRPharmS PGDip IP

Darlington Memorial Hospital, UK

References

- European Medicines Agency. Biosimilar medicines: Overview. 2017. Updated: October 2019. www.ema.europa.eu/en/human-regulatory/overview/biosimilar-medicines-overview (accessed January 2020).

- NHS England. Commissioning framework for biological medicines (including biosimilar medicines) v1.0; 12 Sept 2017. www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/biosimilar-medicines- commissioning-framework.pdf (accessed January 2020)

- Wilkins AR et al. Patient perspectives on biosimilar insulin. J Diabetes Sci Technol 2014;8(1):23–5.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Key therapeutic topic. Biosimilar medicines KTT15. www.nice.org.uk/advice/ktt15 (accessed January 2020).

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Technology appraisal guidance TA188. Human growth hormone (somatropin) for the treatment of growth failure in children. May 2010. www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta188 (accessed January 2020).

- Down S et al. Guideline for the managed introduction of biosimilar basal insulin. Aug 2019. www.guidelinesinpractice.co.uk/supplements/guideline-for-the-managed-introduction-of-biosimilar-basal-insulin/454944.article (accessed January 2020).

- Diabetes UK. Position statement: Biosimilar Insulins. Aug 2019. www.diabetes.org.uk/professionals/position-statements-reports/diagnosis-ongoing-management-monitoring/biosimilar-insulins (accessed January 2020).

- Jayagopal V, Drummond R, Nagi D. Association of British Clinical Diabetologists (ABCD) position statement on the use of biosimilar insulin. Br J Diabetes 2018;18:171–4.

- Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. The Black Triangle Scheme ( or *). June 2009. www.gov.uk/drug-safety-update/the-black-triangle-scheme-or (accessed January 2020).

- Ruszala V et al. An Integrated Career and Competency Framework for Pharmacists in Diabetes. Diabetes UK. www.diabetes.org.uk/professionals/training–competencies/competencies (accessed January 2020).

- Royal Pharmaceutical Society. Advanced Pharmacy Framework. 2013. www.rpharms.com/resources/frameworks/advanced-pharmacy-framework-apf (accessed January 2020).

- Royal Pharmaceutical Society. Foundation Pharmacy Framework. Jan 2014. www.rpharms.com/resources/frameworks/foundation-pharmacy-framework-fpf (accessed January 2020).

- Franklin D; on behalf of NHS England. Commissioning for Quality and Innovation (CQUIN). Specialised Scheme Guidance for 2017-2019. November 2016. www.england.nhs.uk/nhs-standard-contract/cquin/pres-cquin-17-19/ (accessed January 2020).

- Joint Formulary Committee. 2019. British National Formulary. www.medicinescomplete.com (accessed January 2020).