teaser

Mari Nakabayashi

MD PhD

Research Associate

William K Oh

MD

Clinical Director

Lank Center for Genitourinary Oncology

Department of Medical Oncology

Dana-Farber Cancer Institute

Harvard Medical School

Boston, MA

USA

E:[email protected]

Prostate cancer is the most commonly diagnosed cancer in men in the USA aside from skin cancer and has the second highest rate of cancer mortality. The incidence of prostate cancer is highest in North America and western Europe. Efforts to diagnose patients earlier by measuring serum prostatic-specific antigen (PSA) levels have resulted in more patients presenting with curable disease. Primary definitive local treatment with radical prostatectomy or radiation therapy in patients with organ-confined prostate cancer demonstrates 10-year cancer-specific survival of over 75%.(1,2)

Management of localised disease

Patients with high-risk features, such as biopsy Gleason score of 8–10, PSA levels >20ng/ml and a clinical stage T3 disease, are at high risk of recurrence and micrometastatic dissemination at the time of initial diagnosis.(3) Indeed, despite the best available care, approximately 80% of patients with high-risk localised disease will have evidence of biochemical (PSA relapse) or clinical failure within 10 years after the definitive local therapy. PSA relapse often precedes clinical recurrence by many years.(4) The optimal treatment strategy for patients with an asymptomatic rise in PSA levels remains unclear. Although androgen deprivation therapy is commonly instituted early in such patients, optimal timing for such therapy remains uncertain, and, given the subsequent progression of the majority of patients to more advanced disease, new treatment options are needed. Earlier use of chemotherapy is currently under study, but the choice of drug, the endpoint of neoadjuvant therapy and the timing of adjuvant therapy are among the many unanswered questions. Prospective trials are currently underway to test the hypothesis that neoadjuvant and adjuvant chemotherapy may improve survival rate in these high-risk patients (see Table 1). Of note, a phase III study of radiation therapy (RT)/androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) versus RT/ADT followed by chemotherapy of paclitaxel/ etoposide/estramustine (RTOG 9902) was recently closed due to the increased thromboembolic toxicity induced by estramustine.

[[HPE21_table1_74]]

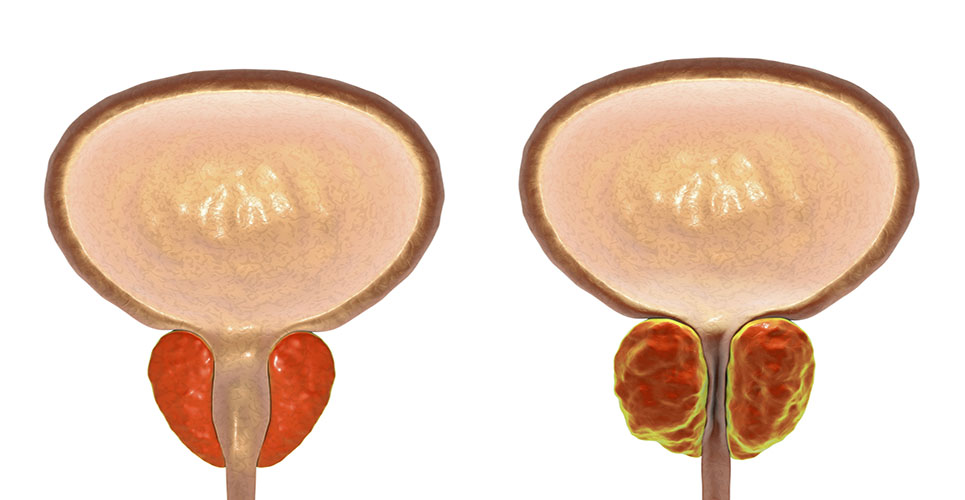

Androgen deprivation therapy by either bilateral orchiectomy or medical castration by utilising luteinising hormone- releasing hormone (LHRH) agonists, followed by antiandrogen blockade, is another treatment for localised disease. Although most patients initially respond to this therapy, almost all will eventually progress to hormone- refractory disease.

Management of hormone-refractory disease

After failure of initial androgen deprivation therapy, continued and further suppression of the androgen axis remains a key factor in the management of hormone- refractory prostate cancer (HRPC). Typical therapeutic strategies include antiandrogen withdrawal, secondary hormonal therapy and chemotherapy. Antiandrogen withdrawal has been described with all antiandrogens, including flutamide, bicalutamide and nilutamide. In a small percentage of patients (10–20%), discontinuation of the antiandrogen will lead to >50% decline in PSA within four to six weeks. Secondary hormonal therapies include the second-line addition of an antiandrogen to continued LHRH-agonist therapy, inhibitors of adrenal steroid synthesis and oestrogenic therapies. (8–21) Symptomatic improvement and PSA declines of >50% have been reported in approximately 20–80% of patients with HRPC. The typical duration of response is two to six months, although long-term responses have been seen. However, treatment is expensive ($1,000 or more per month) and often not covered by insurance. Adverse effects are generally mild, although serious side-effects, including adrenal insufficiency, liver toxicity and thrombosis, may occur.

Taxanes are among the most active chemotherapy regimens tested so far in phase II and III trials. Recently, two landmark randomised phase III trials demonstrated a significant improvement in time to disease progression, pain control, PSA response and, most importantly, survival benefit with docetaxel-based chemotherapy in patients with hormone-refractory prostate cancer (see Table 2). As a result, docetaxel with prednisone every three weeks has become the new standard first-line chemotherapy regimen for HRPC.(5,6) Mitoxantrone plus prednisone confers a palliative benefit in patients with HRPC and remains an option for some patients.

[[HPE21_table2_75]]

New investigational chemotherapy trials are also underway, often involving combinations with docetaxel. For instance, a randomised phase II trial in HRPC patients of docetaxel with or without the immunodulatory drug thalidomide (200mg/day) demonstrated a trend towards longer survival in the combination therapy arm compared with docetaxel alone (68.2% vs 42.9%), although the difference was not statistically significant.(3) Other investigational agents being studied include bevacizumab, imatinib mesylate and calcitriol.

As prostate cancer cells preferentially metastasise to the bone, skeletal complications are a prominent cause of morbidity and mortality among patients with HRPC. Bisphosphonates are currently the most potent class of drugs in the management of the skeletal complications and antiandrogen-associated osteoporosis.(7) Zoledronic acid has been approved for use in patients with HRPC and bone metastases.

Conclusion

Treatment options for management of prostate cancer have undergone significant evolution. Docetaxel plus prednisone has become the first-line chemotherapy regimen based on its survival benefit in patients with HRPC. With an increased understanding of the molecular mechanisms of prostate cancer, various investigational agents targeting specific molecules/pathways are being actively tested in various settings, often in combination with docetaxel. Timing of hormonal therapy/chemotherapy and the sequencing of therapies to improve survival still need to be addressed in prospective studies.

References

- JAMA 1999;281:1598-604.

- J Urol 1994;152:1850-7.

- J Clin Oncol 2004;22:2532-9.

- J Urol 1989;141:873-9.

- N Engl J Med 2004;351:1513-20.

- N Engl J Med 2004;351:1502-12.

- J Urol 2003;170:S55-7; discussion S57-8.

- Urology 2001;58:53-8.

- J Urol 1998;159:149-53.

- J Urol 2003;169:1742-4.

- Urology 2001;58:1016-20.

- J Clin Oncol 1999;17:2506-13.

- J Clin Oncol 2000;18:1440-50.

- J Clin Oncol 1996;14:1756-64.

- J Clin Oncol 1989;7:590-7.

- J Urol 1997;157:1204-7.

- J Clin Oncol 2004;22:1025-33.

- J Urol 2002;168:542-5.

- Urol Oncol 2001;6:111-5.

- Urology 1998;52:257-60.

- J Clin Oncol 2004;22:3705-12.