This brief pilot study report details a small retrospective study undertaken in a UK hospital that looked at the implications of removing prior authorisation (Blueteq) for the biosimilars adalimumab or infliximab when used in inflammatory bowel disease.

Inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) – Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC) – are chronic conditions that require lifelong medical therapy, with the introduction of biologics representing a significant advance in IBD management. The primary aims of IBD management are to induce and maintain remission, reduce the risk of complications and improve patient quality of life.1 Remission can be determined as either clinical or endoscopic.

Escalation to biologics in IBD occurs when conventional options have failed, or contraindications are present. These biologic agents include tumour necrosis factor-alpha inhibitors adalimumab and infliximab (both licensed for CD and UC), and a number of other biologics such as golimumab, vedolizumab, tofacitinib and filgotinb. Biologics are superior to placebo to induce and maintain remission in IBD refractory to conventional therapies, including immunomodulators such as glucocorticoids, thiopurines and methotrexate.2-4

Across England and Wales, guidance from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) assesses the clinical and cost effectiveness of health technologies, including pharmaceuticals. The NHS is legally obliged to fund and resource medicines and treatments recommended by NICE’s technology appraisals (TA).5 NICE’s guidance on IBD describes the various treatment options and identifies the relevant TAs.6,7

Infliximab and adalimumab, within their licensed indications, are recommended as treatment options for adults with severe active CD whose disease has not responded to conventional therapy, or who are intolerant of, or have contraindications to, conventional therapy. NICE also recommends infliximab as a treatment option for people with active fistulising CD within certain conditions.6

For UC, infliximab and adalimumab are recommended, within their marketing authorisations, as options for treating moderately to severely active UC in adults whose disease has responded inadequately to conventional therapy, or who cannot tolerate, or have medical contraindications for, such therapies. Infliximab is also recommended as an option for the treatment of acute exacerbations of severely active UC according to certain criteria.7

Within England there have been a number of ongoing strategies to promote the use of biologic biosimilars in hospitals including educational,8 setting of targets for the proportion of patients who are prescribed biosimilar biologics,9 and monitoring the local adoption of biosimilars by regional teams that facilitate implementation of national policy measures.

Our hospital is a 750-bed acute secondary care hospital in the south-west of England. The Gastroenterology Department developed a simple biologics pathway for IBD which describes use of conventional therapy prior to the use of biologics. It then defaults to the biosimilar adalimumab or infliximab as first choice parenteral treatment. Other biologics may be chosen depending on various patient considerations and whether for UC or CD.

The hospital, in conjunction with the local integrated care board (ICB), utilises the Blueteq high-cost drug management system. ICBs are statutory regional NHS bodies that are responsible for the planning and commissioning of healthcare services for their local area. Many ICBs in England use this Blueteq web-based system which allows clinicians to complete an online proforma for patients prescribed a high-cost medicine, such as a biologic, and receive automatic approval for funding if the patient meets all the relevant criteria which normally reflect the NICE TA guidance. This ensures that clinicians receive the approval to treat whilst placing a particular onus on the doctor to always make the right decision.

The Blueteq system retains as an audit trail the request history – including patient name, drug, indication, criteria for use, date of request, requesting clinician – and whether the request was granted or not. This enables ICBs to monitor the use of expensive treatment so that only treatments prescribed in line with NICE guidelines are reimbursed to the hospital.

The prior approval forms we use stipulate that the patient for whom adalimumab or infliximab treatment is needed has either significant active UC or CD defined by either clinical, endoscopic, radiological or biochemical markers, or is unable to tolerate or has lost response to other disease modifying treatments. In addition, the form allows access to treatment for patients who do not strictly fulfil these criteria by requiring that a documented discussion has occurred by the IBD multidisciplinary team (MDT) as to the reason for the patient requiring biologic treatment.

However, the Blueteq system is associated with an administrative burden for hospital clinical and pharmacy teams as well as for the ICB. In addition, the benefits of the Blueteq system are not well evidenced in the peer reviewed literature. With biosimilar adalimumab and biosimilar infliximab being substantially less expensive than the originator brands, it was agreed by the predecessor organisation to the ICB that Blueteq would no longer be needed from March 2022 and that there would be a review of any impact of removing this prior authorisation after approximately 12 months.

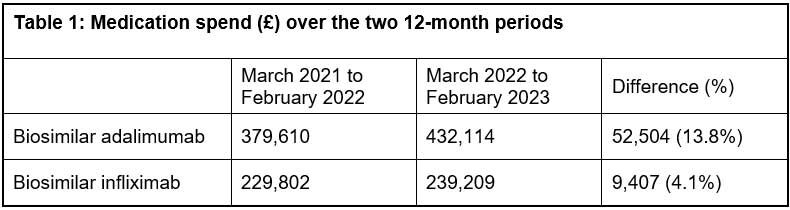

We aimed to examine the medication expenditure for all patients started on these two biosimilars, comparing 12 months to February 2022 with 12 months to February 2023, and to describe the characteristics of a sample of patients commenced on these biosimilars.

Methods

This was a retrospective, single site study. Biosimilar expenditure over the two time periods for all patients was imported into Excel by a member of the pharmacy team. The first cohort of 20 patients who had commenced on the biosimilars adalimumab or infliximab since March 2022 and who had also received a review of their treatment at approximately 14 weeks were included. Relevant data (patient demographics including disease severity index) were collected by a member of the IBD team.

Health Research Authority criteria about research and service evaluation were considered. This was a retrospective assessment involving no changes to the service delivered to patients, and we used the NHS Health research authority tool, which helped confirm that no ethical approval was required for this project. Patient data were used in accordance with local NHS hospital policy.

Results

As regards the medication expenditure for the biosimilars, there was a 13.8% increase in spend on adalimumab and a 4.1% increase in spend on infliximab over the observed time periods. This was on a background of limited and quite stable expenditure on the originator brands (Humira and Remicade). Two brands of biosimilar adalimumab and three brands of biosimilar infliximab were in use over these two time periods, though the first-choice brands of Imraldi and Zessly accounted for 89% and 76% of the respective spends over the full 24 month period. There was no significant alteration in unit price of these biosimilars over this time.

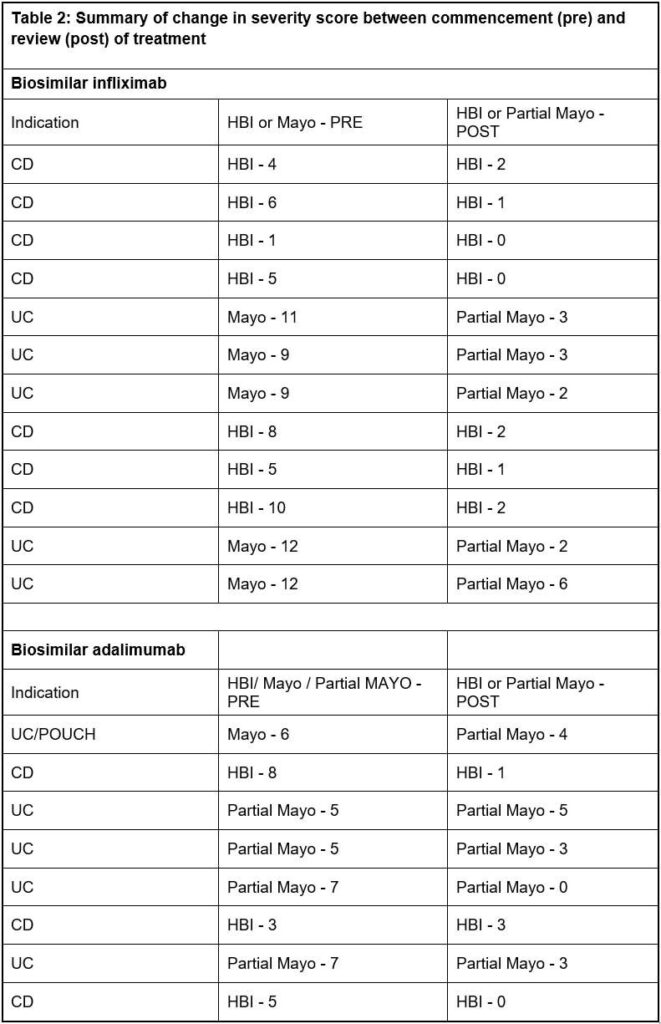

The records of 20 patients – mean age 48 (range 20 to 83 years), 12 female – were reviewed. A total of 12 patients received biosimilar infliximab (seven for CD, four for UC, and one for unspecified IBD) and eight biosimilar adalimumab (three for CD, four for UC, one for unspecified IBD). All 20 patients had a pre- and post-review disease activity score.

The Mayo or partial Mayo was the scoring tool used for eight patients with UC and for the two patients with unclassified IBD, whilst for all 10 patients with CD the Harvey-Bradshaw

Index (HBI) score was used. Some 10 (50%) of the 20 patients had been discussed at a MDT meeting. Following the individual patient review at approximately 14 weeks, 18 (90%) patients demonstrated a reduction in their disease activity score whilst two did not change. Of all 20 patients, one patient on infliximab and two on adalimumab switched to a different biologic.

Discussion

This small-scale study found that there was no dramatic increase in expenditure on the two named biosimilars as a consequence of removing the need for prior authorisation, with a 13.8% increase in spend on adalimumab and a 4.1% increase in spend on infliximab over the observed time periods of 12 months to February 2022 compared with 12 months to February 2023.

It is difficult to compare expenditure on these biosimilars with a previous 12-month time period (March 2020 to February 2021) due to the impact that the pandemic had on the hospital’s IBD service. There was a reduction in biosimilar adalimumab expenditure of 5.6% and a reduction in biosimilar infliximab expenditure of 8.5% between the 12 months to February 2021 compared to 12 months to February 2022, due to fewer patients receiving these medicines during the pandemic.

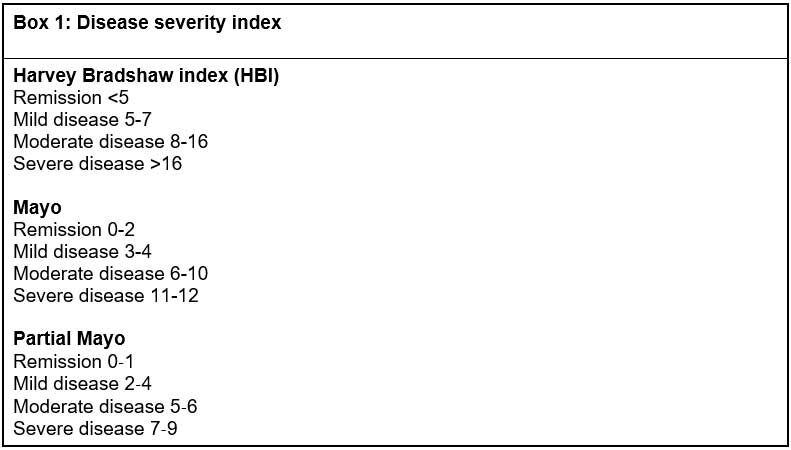

CD severity is based on the assessment of overall patient wellbeing, frequency of diarrhoeal stools, intensity of abdominal pain, presence of extraintestinal symptoms and presence of complications. The HBI or Crohn’s Disease Activity Index (CDAI) tools are often used to assess disease severity in clinical trials.10,11

In its guidance, NICE uses a clinical definition for severe active CD that normally, but not exclusively, corresponds to a CDAI score of 300 or more, or a HBI score of 8 to 9 or above.6 The CDAI is impractical for use in routine clinical practice and has limitations such as including a physician-completed complex calculation, the weight placed on subjective complaints such as general wellbeing and abdominal pain, and the requirement of the patient to keep a diary for seven days. Instead, the HBI is typically used.

NICE guidance further advises that treatment with infliximab or adalimumab should only be continued if there is clear evidence of ongoing active disease as determined by clinical symptoms, biological markers and investigation, including endoscopy if necessary.

Three of the 10 patients with CD had a HBI score of 8 or above, and one other patient had been discussed by the MDT. The remaining six had a score less than 8. The HBI is a useful index with ease of assessment in outpatient telephone clinics, but symptoms may not always be related to the level of inflammation, and it is recognised that there are limitations to the sole use of such a scoring system.1,12,13

We aim to base treatment decisions on NICE and the NICE-accredited British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG) IBD management guidelines as the BSG guideline also covers treat-to-target and acknowledges treatment escalation in less severe but refractory disease.1

Though NICE recommends infliximab and adalimumab as treatment options for adults with severe active CD, for some biologics (e.g. ustekinumab) NICE guidance recommends the biologic as an option for treating moderately to severely active CD.14 European guidelines also recommend the use of infliximab, adalimumab, and certolizumab pegol in moderate to severe CD.15 Awareness of these guidelines may be why six of our patients had a lower HBI when commencing treatment than described in the NICE guidance.6

For UC, NICE guidance refers to mild, moderate and severe categories based on the Truelove and Witts’ severity index.7 The Truelove and Witts score presents some challenges in the outpatient setting, particularly when many assessments are undertaken over the phone, making parameters such as heart rate and temperature invalid. As such, the Mayo or partial Mayo score is utilised as a validated alternative recommended by BSG.

The Mayo score was developed as a composite disease activity index for use in clinical trials and measures stool frequency, rectal bleeding, mucosal appearance at endoscopy and physician’s global assessment, giving a maximum total score of 12.16 In clinical practice, endoscopy is not performed at every visit, and the partial Mayo score was initially developed to address this limitation. It has subsequently been used for endpoint assessment in real-world observational cohort studies in UC.17 Our patients with UC and the two with IBD-unclassified all had a Mayo or partial Mayo score prior to treatment consistent with moderate or severe disease.

It is acknowledged that there are no formally validated definitions of mild, moderate, or severe UC. Instead, scoring systems are based on historical definitions that have been shown to be useful in distinguishing patients into categories of disease likely to respond to various treatments.1,18 For instance, it is argued that two components of the Mayo score, the physician’s global assessment and the endoscopy sub score, are subjective and introduce variability and a lack of precision into the index.19

We recognise the limitations of our approach to ascertaining any impact of removing the Blueteq prior approval form. This was a single-centre, very small-scale study and we do not report follow up of patients beyond their first review at 14 weeks (though this was not central to the aim of our study). These results therefore cannot be generalised to other hospitals and to other indications for these biosimilar medicines.

We focused on the use of two biosimilars only as the prescribing of the originator biologics of Humira and Remicade was minimal at only 6% of the total expenditure for all adalimumab plus infliximab products over both time periods.

We acknowledge that the impact of the pandemic over the time periods we studied, and the rising prevalence of IBD and the potential for changes in practice over time, may also have contributed to any changes in expenditure that we observed.

We looked at a sample of patients commenced on biosimilars over a 12-month period and this sample may not be representative of the wider population. Furthermore, we had no historical data for individual patient reviews and so we do not know whether the proportion of patients meeting NICE guidance on disease activity has changed.

Conclusion

This small study has not raised any immediate concerns over the financial impact of removing the prior authorisation process. These initial results describing the degree of severity for the UC patients prior to biosimilar treatment may suggest the need for a larger study of any impact of ceasing the Blueteq requirement.

Key points

- Various biologic agents, including tumour necrosis factor-alpha inhibitors adalimumab and infliximab, are recommended by National Institute for Health and Care Excellence technology appraisal guidance for the management of inflammatory bowel disease

- Many integrated care boards in England use the Blueteq high-cost drug management system for assurance that expensive treatments, such as biologics, are prescribed in line with NICE guidelines

- In this small retrospective study, no immediate concerns over the financial impact of removing the prior authorisation process for biosimilars of adalimumab and infliximab were observed.

Authors

Michael Wilcock M.Phil

Pharmacy Department

Francesca Fairhurst BSc (Hons)

Gastroenterology Department

Both of Royal Cornwall Hospitals NHS Trust, Truro

Declaration of interest: the authors have no interests to declare.

References

1. Lamb CA, Kennedy NA, Raine T, et al. British Society of Gastroenterology consensus guidelines on the management of inflammatory bowel disease in adults. Gut 2019;68(Suppl 3):s1-s106.

2. Hanauer SB, Feagan BG, Lichtenstein GR, et al. Maintenance infliximab for Crohn’s disease: the ACCENT I randomised trial. Lancet 2002;359:1541–9.

3. Hanauer SB, Sandborn WJ, Rutgeerts P, et al. Human anti-tumor necrosis factor monoclonal antibody (adalimumab) in Crohn’s disease: the CLASSIC-I trial. Gastroenterology 2006;130:323–33.

4. Feagan BG, Rutgeerts P, Sands BE, et al. Vedolizumab as induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med 2013;369:699–710.

5. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. NICE technology appraisal guidance. (accessed March 2023).

6. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Crohn’s disease: management. NICE Guideline (NG129). May 2019. (accessed March 2023).

7. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Ulcerative colitis: management. NICE Guideline (NG130). May 201. (accessed March 2023).

8. NHS England. What is a biosimilar medicine? 2023 (accessed March 2023).

9. NHS England. Commissioning framework for biological medicines (including biosimilar medicines? 2017. (accessed March 2023).

10. Harvey RF, Bradshaw MJ. A simple index of Crohn’s-disease activity. Lancet 1980;1:514.

11. Best WR, Becktel JM, Singleton JW, et al. Development of a Crohn’s disease activity index. National Cooperative Crohn’s Disease Study. Gastroenterology 1976;70(3):439-44.

12. Peyrin-Biroulet L, Panés J, Sandborn WJ, et al. Defining disease severity in inflammatory bowel diseases: Current and future directions. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2016;14(3):348-354.e17.

13. Lichtenstein GR, Loftus EV, Isaacs KL, et al. ACG Clinical Guideline: Management of Crohn’s disease in adults. Am J Gastroenterol 2018;113(4):481-517.

14. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Ustekinumab for moderately to severely active Crohn’s disease after previous treatment. TA456, July 2017. (accessed March 2023).

15. Torres J, Bonovas S, Doherty G, et al. ECCO Guidelines on Therapeutics in Crohn’s Disease: Medical Treatment. J Crohns Colitis 2020;14(1):4-22.

16. Schroeder KW, Tremaine WJ, Ilstrup DM. Coated oral 5-aminosalicylic acid therapy for mildly to moderately active ulcerative colitis. A randomized study. N Engl J Med 1987;317:1625–1629.

17. Lewis JD, Chuai S, Nessel L, et al. Use of the noninvasive components of the Mayo score to assess clinical response in ulcerative colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2008;14:1660–1666.

18. Pabla BS, Schwartz DA. Assessing severity of disease in patients with ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 2020;49(4):671–688.

19. Cooney RM, Warren BF, Altman DG, et al. Outcome measurement in clinical trials for ulcerative colitis: towards standardisation. Trials 2007;8:17.