This article outlines outcomes of the CHAMOIS team. This clinical pharmacy service for vulnerable care home residents commissioned in 2013 is now an integral part of NHS Leeds West Clinical Commissioning Group medicines optimisation teams’ work

Helen Whiteside MRPharmS IP BPharm (Hons) Clin Dip Pharm

NHS Leeds West Clinical Commissioning Group

Email: [email protected]

This article outlines outcomes of the CHAMOIS team. This clinical pharmacy service for vulnerable care home residents commissioned in 2013 is now an integral part of NHS Leeds West Clinical Commissioning Group medicines optimisation teams’ work

Helen Whiteside MRPharmS IP BPharm (Hons) Clin Dip Pharm

NHS Leeds West Clinical Commissioning Group

Email: [email protected]

The need to improve the management of medicines in care homes has been highlighted1–7 as have the increased risks during transfer of care between care settings.

Clinical pharmacy services are embedded in secondary care but are less well established in primary care. A key component is medication review, which is recognised as an essential element of safe prescribing6 and has been defined as ‘a structured, critical examination of a patients’ medicines with the objective of reaching an agreement with the patient about treatment, optimising the impact of medicines, minimising the number of medication-related problems and reducing waste’.8

The Care Homes and Medicines Optimisation Implementation Service (CHAMOIS) team, consisting of 1.8 WTE clinical pharmacists undertook clinical medication reviews incorporating a holistic patient assessment in care homes for older people for GP practices across the clinical commissioning group (CCG). Figure 1 highlights the process they followed.

Once a GP practice had agreed for the pharmacist to support care of their care home residents, the pharmacist would:

- Review the care home residents’ GP based medical records.

- Request appropriate monitoring tests and observations.

- Visit the care home, view their records and talk to the carer(s).

- Reconcile the residents’ medicines administration record (MAR) charts with their current medicines list from the GP records.

- Where a resident had capacity, discuss care priorities and medicines with the resident, engaging with family members or advocates as appropriate.

- Liaise with other healthcare team members and non-medical prescribers.

- Record medication review findings in the GP practice records.

- Make recommendations to GP for medicines changes, monitoring tests and care planning.

- Agree actions and medicines changes to be made.

- Make medicines changes and ensure actions take place.

- Communicate in writing that the medication review has taken place and the agreed. medicine changes, monitoring criteria and personalised care plans to the resident and the dispensing community pharmacist to ensure safe management of medicines at all stages. (CHUMS, NCF and NICE.1–3

- Follow residents up about two to four weeks after medicine changes have taken affect in the repeat prescribing system to ensure care plan has been implemented, is acceptable to the resident and producing the intended outcomes.

Figure 1: Summary of medication review process

Once all residents registered at one GP practice had been completed reviews, the pharmacist would relocate to another GP practice and start the process again.

Findings

Process and clinical quality and safety summary

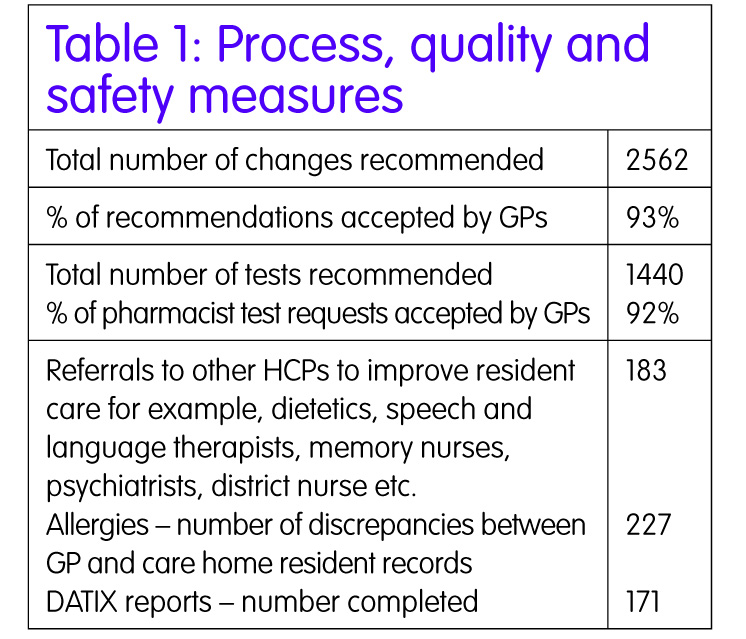

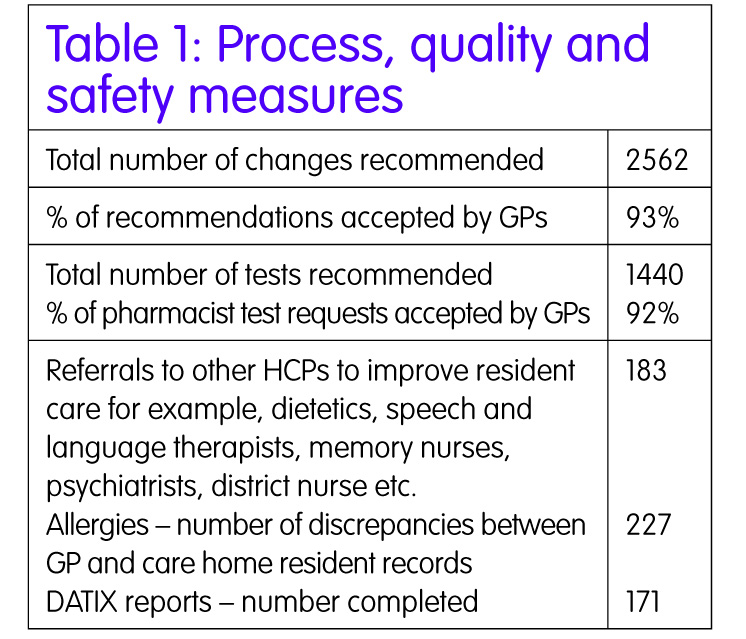

To ensure consistency of service provision, an SOP and a medication review tool were developed and key performance indicators (KPIs) defined. Process, safety and quality measures (Table 1) were designed to demonstrate:

- Workload, (number of residents reviewed and changes being made to medication)

- Safety of medication prescribing (number of monitoring tests requested to monitor medication according to national safety standards9

- Acceptability of the clinical pharmacists recommendations to GPs

Quality of care – ensuring care is coordinated (number of referrals to appropriate care settings) and quality of care improved (interventions to match allergy status and number of DATIX® reports).

Overall, GPs accepted 93% of our recommendations. Consistent with published literature this demonstrates a high degree of comparable decision making between the pharmacists and GPs.

Recommendations concerning changes to psychiatry medications had much lower acceptance rates. This was attributed to GPs lack of familiarity with these medicines started and monitored by specialists and concerns around how care homes would manage the residents’ behaviour without use of medication. This has significant implications for primary care where long-term care, monitoring and medication review for those prescribed anticholinesterases is being transferred from specialists to GPs. The safe prescribing of antipsychotics and sedatives are the focus of guidelines,10 which many of our GPs appeared unfamiliar with and will be the focus of future education events.

In addition to recording up-to-date fundamental information essential for a holistic assessment which was absent from GP records for example weight, blood pressure, mobility, nutrition, hydration and continence; at least two blood tests were required for all residents to ensure their medicines and diseases had been adequately monitored within the last year. Obtaining these had a resource implication for practices and was often the cause of a delay in the review process. Since the introduction of care coordinators in some of the CCGs’ practices in 2015, this delay has reduced. GPs accepted 92% of our test requests. The acceptance rate was much higher where practices actively used EPaCCS (Electronic Palliative Care Co-ordination Systems) or the GSF (Gold Standards Framework) to document residents’ prognosis which was taken into account by the team before making recommendations.

By undertaking a holistic patient approach not just a medication review, the team identified residents that required referral to a specialist such as speech and language for swallowing problems or dieticians where a downward weight loss trend was found. The pharmacist became the care coordinator ensuring that specialists who were providing care to residents prior to their admission to the care home were made aware of their current address and could continue care, or remove them from case loads as clinically appropriate. It was found that 27% of residents required a referral/reconnection.

Three in every ten residents had a mismatched allergy status between the GP and the care home records. This could be reduced if adequate and safe medicine and allergy reconciliation processes were undertaken by practices and care homes as per the NICE guidance.3 To demonstrate the value of the clinical pharmacist to the care home residents, the team created Doris, an animated character whose story was taken from real life examples of interactions with healthcare and the pharmacists. This and views of healthcare professionals and carers about our service can be found at http://www.leedswestccg.nhs.uk/news/leeds-care-home-patients-benefit-medication-review-service/.

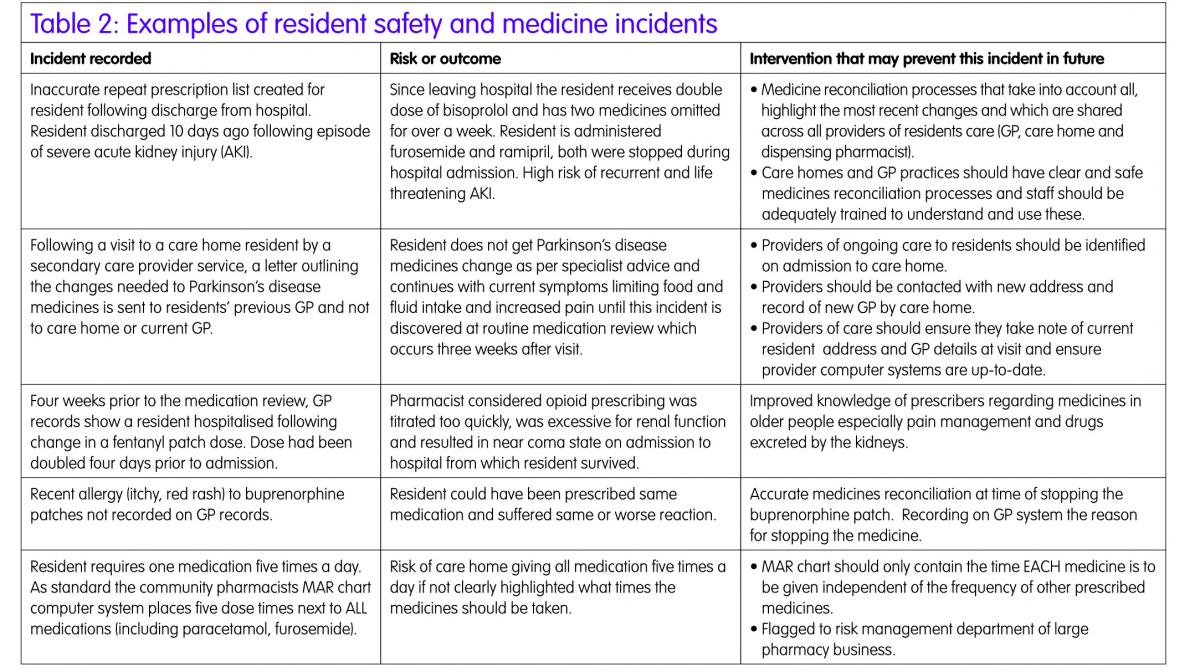

Identified resident and medicines safety incidents were reported on DATIX® and discussed with relevant parties. These 171 incidents originated from a variety of sources including prescribers, GP practice and care home processes, care home staff, community pharmacies and a range of care providers in Leeds. Examples are shown in Table 2.

The team raised a wide range of medicine safety issues in homes to the cross-city medicines safety team. This highlighted a need for additional staff to support inspection and quality improvement which has been secured for this team. Our findings were incorporated into at least one city council inspection and two CQC inspection reports.

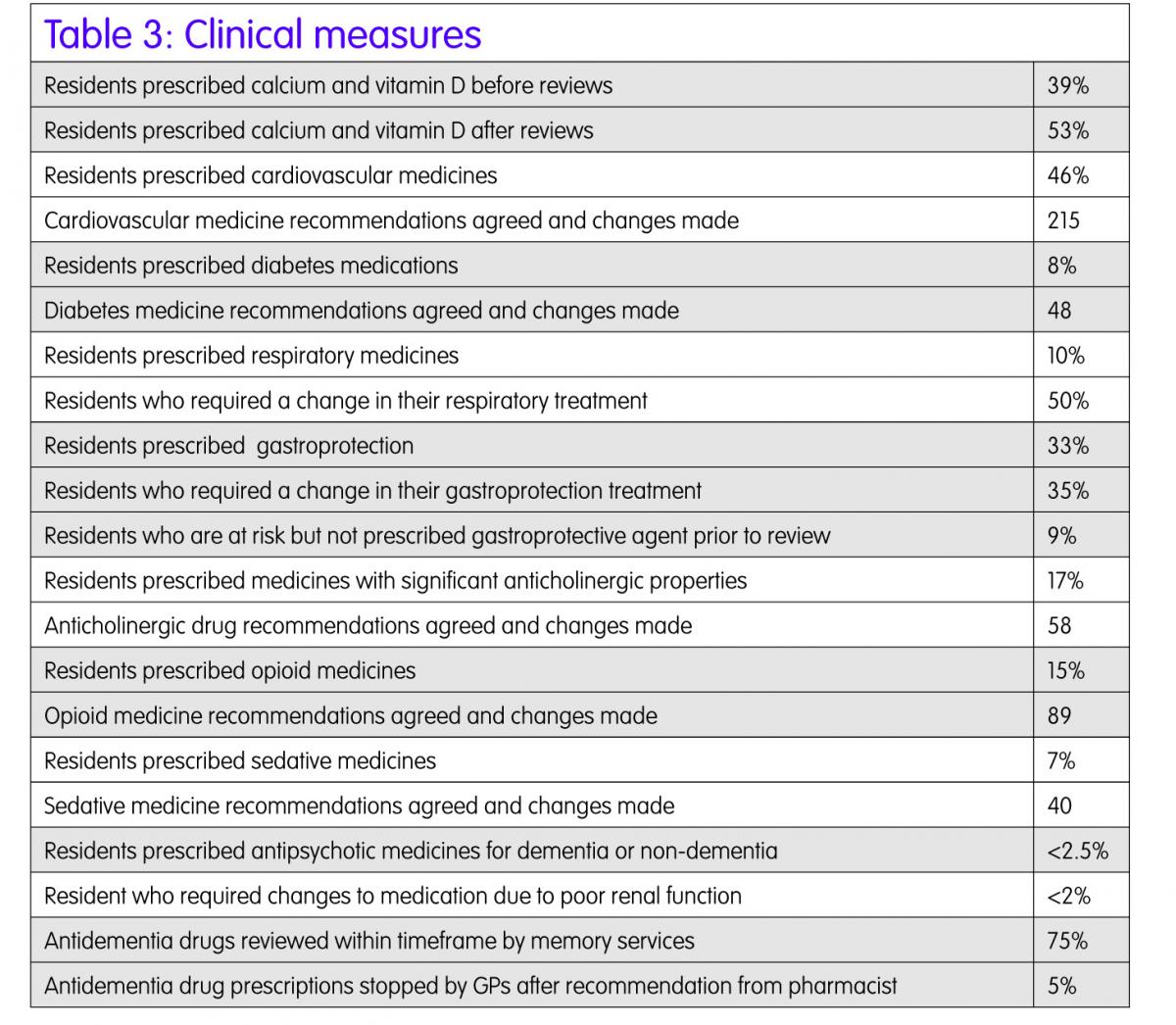

Clinical measures

A clinical data set was designed to incorporate some of the CCGs priority areas such as diabetes, cardiovascular, respiratory; as well as specific areas of concern relating to medicines in the older population (Table 3). Medicine such as anticholinergics, sedatives and opiates, which are linked to an increased falls risk or those with a high risk profile, for example, antipsychotics were reported on as interventions in these areas could potentially reduce hospital admissions.

To minimise the risk of falls and subsequent fractures the team implemented prescribing of calcium and vitamin D as per current guidance. The acceptability of these preparations to residents limits the take up of these preparations as did the current health status of our residents some of whom were bed bound and at the end of life where this medicine was not a high priority for them.

Almost half of residents were prescribed a cardiovascular medication some of which were stopped. These included antihypertensives where blood pressure was too low, medicines for exertional angina where residents now had significantly reduced mobility or were bed bound or preventative treatments such as statins in residents who have a life-limiting condition. Our work was not all about stopping medicines, deprescribing;11,12 some medicine changes were made after diagnosing conditions that required treatment such as hypothyroidism or postural hypotension requiring fludrocortisone.

Over half of the residents prescribed respiratory medicines required changes including step down of high strength steroid inhalers or changes in inhaler devices or provision of additional aids to maximise drug delivery.

We found many residents receiving gastroprotective agents in whom we safely reduced the dose or stepped down and stopped treatment without symptoms. With the emerging of concerns relating to increased risks of osteoporosis, pernicious anaemia and pneumonia in residents taking acid suppressing agents it is important to ensure the minimum effective dose is prescribed and that when antiplatelet or non-steroidal medicines are no longer prescribed the accompanying gastoprotective agent is also stopped. In contrast, we found 9% of our residents at risk of GI bleeding from the combination of prescribed medication and medical conditions and initiated gastroprotective agents.

Much work has been done in the past decade to reduce hypnotic and anxiolytic prescribing. We found significant numbers of residents taking opioid and other medicines with anticholinergic or sedative properties that predispose to falls. In this frail, elderly population where the medical complications of fractures and subsequent hospital stays has a high mortality it is essential to keep prescribing of these medicines to a minimum. For example, many residents were found still being treated with ineffective urinary incontinence medicines and requiring management with pads.

Pain management was not often found following the national and local prescribing guidance for older people. Opioids were being introduced before adequate trials of non-opiate medication, opiate doses titrated up too quickly and long acting preparations such as patches prescribed which are not suitable for dose titration. Laxatives were rarely prescribed at the start of opioid treatment resulting in constipation in the majority of residents which along with opiate doses in excess of the recommended doses for renal impairment had clearly resulted in some avoidable hospital admissions. Prescribing for the elderly in general and in particular pain management is a key area that needs to be addressed through educational sessions. Figure 2 outlines some resident scenarios.

Financial outcomes

Total expenditure during project was £123,532, making this project cost neutral on drug cost savings alone.

Eadon Score13–15

The School of Healthcare and Related Research at Sheffield University (ScHARR) has defined the costs related to medication interventions and errors. The financial values assigned to these, together with the Eadon criteria representative of whether the intervention can prevent a potentially significant, potentially serious or potentially lethal event.

As a result of the clinical and other medicine related changes, synchronisation of allergy status records and referrals for specialist interventions, using this methodology, the avoidable healthcare costs as a result of the pharmacists’ interventions were a minimum of £268,737 up to a maximum of £588,544. When applied to the 171 safety incidents the costs avoided are calculated at £69,680 minimum and £143,506 maximum.

Overall, the potential cost avoidance using the published, evidence based Eadon scores and ScHARR modelling was a minimum of £338,417 to a maximum of £732,050.

Discussion

The CHAMOIS project was a finalist at the 2014 HSJ Value and Improvement in Medicines Management awards, has been celebrated at CCG board level and it has received very positive feedback from residents, relatives and healthcare workers.

The results from this two-year project support the successful bid for four permanent senior clinical pharmacist posts in the medicines optimisation team.

The impact of these clinical medication reviews on the cost-effectiveness, safety and quality of prescribing and medicines management in care homes has been recognised and incorporated as a key element into the CCG integrated GP care home service from August 2015. The pharmacists will now perform medication reviews on all new and post discharge care home residents as part of their role and will be part of a clinical network learning with GPs and nurses and conducting sessions relating to good quality care and appropriate prescribing for frail and elderly people. They aim to support GP practices to review new patient registration, medicine reconciliation, and repeat prescribing policies and systems to ensure they are sufficiently robust to minimise errors and maximise effectiveness of the system in line with NICE guidance.3,4

Acknowledgement

It is wished to thank Nicola Shaw and Helen Higgins the other Clinical Care Pharmacists who have been instrumental in the development and operation of the project and Sally Bower Head of Medicines Optimisation, NHS Leeds West Clinical Commissioning Group.

Resident preference of medicines optimisation

Medication review highlights that a resident does not take her medicines, most often in the morning. She likes to get out of bed late. Some medicines are large and hard to swallow. She is prescribed 10 medicines which means 25 doses of medicines throughout the day – too many she feels. The pharmacist along with the GP reduces the list of medicines, choosing the medicines that will give the resident the most benefit and then the pharmacist changes the times and the formulations to ones that suit the daily schedule of the resident. She now takes eight medicines regularly including cardiovascular, diabetes and mental health medication.

Post-discharge

A review at a residential home highlighted that a resident recently discharged from hospital has been receiving a drug that had been stopped in the hospital. The diuretic had been stopped due to acute kidney injury. The carers at the home had not crossed the drug off the medication administration record (MAR) chart after her return from hospital 10 days ago. There was a significant risk that resident would have been readmitted for same problem due to incorrect medicine changes post discharge.

A resident on three vitamin supplements for at least six months prior to review since discharge from hospital. Following a discussion with a dietetic colleague we agreed these were no longer clinically indicated and they were stopped. The resident was delighted as that was 10 tablets per day she no longer needed to take.

New resident/prevention of hospital admission/quality of care – follow-up

New resident – medicines reconciliation

Medicine reconciliation for a new resident highlighted that repeat prescription on GP computer system of colecalciferol for vitamin D deficiency was ambiguous. It did not state dose was weekly or that it was to stop after eight weeks. Directions clarified, MAR chart altered to ensure weekly administration. Risk of vitamin D overdose was averted.

New resident – monitoring of medicines

An 82-year-old lady new resident had been recently been diagnosed with fast AF in hospital. She had been treated with digoxin prior to discharge and is currently prescribed 125?g per day.

Pharmacist advised digoxin level was taken as they were concerned that long term dose prescribed by hospital may be too high for this resident given their current symptoms and their other medical conditions. Blood test taken and the digoxin level was significantly high and required the dose to be reduced by care home pharmacist.

If no dose change had taken place it would be highly likely the resident would have required readmission to hospital for additional medical care.

New resident – ensuing links to specialist services are kept, for example, memory nurses

Over 25% of residents with dementia who were currently prescribed an anticholinesterase inhibitor have been put back in touch with the specialist nurses that follow up and monitor their dementia medicines. These residents had been lost to the specialist service as they had moved into new addresses at the care homes and to different GPs and the nurses had not been aware of these changes.

New resident – ensuring links to specialist services are kept, for example, dieticians

Very frail resident required nutritional supplements to be prescribed by her GP to maintain her weight. She had previously been under the care of dieticians in Bradford. The medication review highlighted the need for continuous follow-up by a dietary service and so a referral was made to the Leeds Eating and Drinking Service. The required items were placed on the repeat prescription screen to they could be continually accessed.

End of life

Several residents in their last few weeks of life were admitted to a care home whilst pharmacist was carrying out medication review in the home. The doses of some of their medicines were excessive for current clinical conditions and were reduced or stopped entirely. In one resident medication changes resulted in cessation of nausea, she began eating and drinking again and improved sufficiently to live well for another six months.

Monitoring for safety and effectiveness of medicines

Ensuring that residents had regular annual blood monitoring tests allowed the pharmacists to optimise the medicines to ensure the residents are prescribed the appropriate dose. Taking the right dose of some medicines makes the resident feel better and in the case of diabetes – reduces the risk of developing serious kidney, eye and blood vessel disease in the future. It has also identified residents who needed additional medicines to treat their previously known and sometimes previously undiagnosed conditions.

A number of residents who have had specialist mental health drugs prescribed for a number of years have been re-referred for a specialist psychiatry review to see if these medicines are still required. In several cases the doses have been successfully reduced and stopped altogether. This supports the national initiatives to reduce the use of medicines such as antipsychotics and hypnotics which although effective have been associated with increased mortality.

A resident is experiencing an excessive amount of drooling which is upsetting them. Rather than add in another drug to stop this (with its own side effects), the pharmacist recommended a small reduction in dose of one of the residents’ other drugs which could be causing the drooling as a side effect. The drooling is reducing and becoming less distressing.

A number of residents have successfully had the doses of their antidepressants slowly reduced or stopped after being on treatment for a few years. Feedback from residents, carers and families has been very positive. The residents are still well, have generally become more sociable and chatty with staff and other residents as they are far less sleepy.

A number of residents have been able to stop taking iron tablets after having blood tests taken which show that they are no longer anaemic. Iron tablets can cause constipation which if not dealt with promptly, especially in residents unable to communicate their needs such as some with dementia, can become severe and result in delirium and result in hospital admission.

A resident receiving two urinary incontinence medicines for several months in error had one of these medicines stopped. Continence was maintained and the risk of falls or urinary retention or potential hospital admission reduced.

Referral to other services

Two residents’ symptoms and subsequent blood test results indicated possible heart failure. They have been referred to a heart failure specialist nurse for further tests and new treatments.

A resident at a residential care home was having bowel and bladder problems that could were possibly related to her medicines. The resident was referred to the incontinence nurse who was able to scan the residents’ bladder, diagnose the problem, and provide the correct treatment and ongoing support.

New diagnosis

Residents found at the medication review to have a blood pressure above the recommended limits have been started on medicine to lower the blood pressure; to reduce the risks of heart attacks and strokes.

Residents found to be anaemic had additional tests requested by the pharmacist to identify the cause. This identified they needed iron supplements, which were prescribed.

Figure 2: Case scenarios

Key points

- Pharmacists can demonstrate impact on safety and quality of prescribing when undertaking medication reviews and as such their success should be measured on more than cost savings from medicine changes.

- Medication review must be carried out as part of a holistic resident centred review with the resident (or a representative), taking into account their care goals and wishes.

- The medication review should be carried out by an experienced pharmacist with clinical and medicine information knowledge, patient consultation and counselling skills and the ability to work as a care coordinator within a multidisciplinary team.

- There is a key role for pharmacists to improve primary care systems and processes to deliver appropriate medicines for care home residents medicines.

- The focus of future work should be to measure resident defined and clinical outcomes.

References

- Barber ND et al. Care homes’ use of medicines (CHUMS) study: prevalence, causes and potential harm of medication errors in care homes for older people. Qual Safety Healthcare 2009;18:341–6

- National Care Forum on behalf of the Care Provider Alliance. Final project report – Phase 2. Safety of medicines in the care home. National Care Forum .2013. www.patientsafety.health.org.uk/sites/default/files/resources/safety_of_medicines_in_the_care_home_0.pdf. (Accessed 11 September 2015).

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Managing medicines in care homes. NICE guidelines [SC1]. London: NICE; 2014. www.nice.org.uk/guidance/sc/SC1.jsp. (Accessed 11 September 2015).

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Managing medicines in care homes. NICE Quality standard 85. London: NICE; 2015 www.nice.org.uk/guidance/qs85. (Accessed 11 September 2015).

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Managing medicines in care homes. NICE Commissioning guidance 85. London: NICE; 2015 www.guidance.nice.org.uk/sfcqs85. (Accessed 11 September 2015).

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Managing older people in care homes. NICE Local government briefing 25. London: NICE; 2015 www.publications.nice.org.uk/lgb25. (Accessed 11 September 2015).

- Report and Action Plan of the Steering Group on Improving the Use of Medicines (for better outcomes and reduced waste). Improving the use of medicines for better outcomes and reduced waste: An Action Plan. 2012. www.sduhealth.org.uk/documents/waste_medicines_action_plan_DH.pdf. (Accessed 11 September 2015).

- Task Force on Medicines Partnership and the National Collaborative Medicines Management Services Programme. Room for Review. A guide to medication review: the agenda for patients, practitioners and managers. London: Medicines Partnership, 2002.

- NHS. United Kingdom Medicines Information Service (UKMI). Suggestions for Drug Monitoring in Adults in Primary Care. Collaboration between London and South East Medicine Information Service, South West Medicine Information Service and Croydon Clinical Commissioning Group. February 2014. www.medicinesresources.nhs.uk/upload/documents/Evidence/Drug%20monitoring%20document%20Feb%202014.pdf. (Accessed 11 September 2015).

- Leeds Integrated Dementia Board. Leeds Area Prescribing Committee. Managing behavioural and Psychological Disturbance in Dementia. A guidance and resource pack for Leeds. December 2013 www.leeds.gov.uk/docs/Leeds%20guideline%20-%20Behavioural%20and%20Psychological%20Needs%20in%20Dementia.pdf. (Accessed 11 September 2015).

- East and South East England Specialist Pharmacy Service. New approaches to Polypharmacy, oligopharmacy and deprescribing. London: 2014. www.medicinesresources.nhs.uk/upload/documents/Communities/SPS_E_SE_England/Presn_OPNet_19Nov13_New_approaches_Polypharm_Oligopharm_and_deprescribing_NB_LO.pdf. (Accessed 11 September 2015).

- East and South East England Specialist Pharmacy Service. A patient-centred polypharmacy. Version 12 Updated July 2015. www.medicinesresources.nhs.uk/en/Communities/NHS/SPS-E-and-SE-England/Meds-use-and-safety/Service-deliv-and-devel/Older-people-care-homes/Polypharmacy-oligopharmacy–deprescribing-resources-to-support-local-delivery/. (Accessed 11 September 2015).

- Eadon H. Assessing the quality of ward pharmacists’ interventions. Int J Pharm Prac 1992;1:145–47.

- Newman C and Bailey A. A safer approach to hospital pharmacy. Health Serv J 2012;12(6312):21–3.

- Kamon J et al. Modelling the expected net benefits of interventions to reduce the burden of medication errors. J of Health Serv Res and Pol 2008;13(2):85–91.

- www.medicinesresources.nhs.uk/upload/documents/Evidence/Drug%20monitoring%20document%20Feb%202014.pdf. (Accessed 29 July 2015).