As hospitals in the National Health Service face ever-increasing demands on their services from an increasingly elderly population, hospitals are induced to re-examine their models for the delivery of complex therapies

David de Monteverde-Robb BSc(Hons) DipPharmPract MSc(ClinRes) MRPharmS ADA

Head of Pharmacy Research, Clinical Pharmacy Lead for Immunotherapies, Neurosciences and Perioperative Medicine, Addenbrookes Hospital, Cambridge, UK

Email: [email protected]

As hospitals in the National Health Service face ever-increasing demands on their services from an increasingly elderly population, hospitals are induced to re-examine their models for the delivery of complex therapies

David de Monteverde-Robb BSc(Hons) DipPharmPract MSc(ClinRes) MRPharmS ADA

Head of Pharmacy Research, Clinical Pharmacy Lead for Immunotherapies, Neurosciences and Perioperative Medicine, Addenbrookes Hospital, Cambridge, UK

Email: [email protected]

Since 1995, the scope of homecare medicine has grown far beyond the originally identified therapies. It now includes various high and low technology medicines and services, from chemotherapy to dialysis to delivery of HIV medicines.1 In recent years there have been concerns around the governance arrangements for homecare provision and in April 2014, NHS England issued an alert to NHS Trusts stating that reports of drugs failing to be delivered on time had ‘increased significantly’.2 It instructed Trusts to put alternative methods of supply in place for patients whose deliveries were delayed and to assess the capabilities of commercial providers before assigning more patients to them.

Nevertheless the introduction of home therapy programmes has given many patients a better quality of life as it is more convenient than receiving infusions at hospital and allows patients to have greater control over their condition.3 As outlined in the NHS England Productivity and Efficiency Handbook (2013/2014)4 for the NHS, all specialist immunology and allergy services should look to offer a home treatment service for long-term immunoglobulin replacement, consistent with the recommendations of the National Immunoglobulin Demand Management Programme, with appropriate monitoring, training and governance.

Since the time of their advent, UK homecare providers have widely broadened their range of services and have a proven track record in the delivery of a wide range of therapies. Accordingly, homecare is increasingly a viable option for pathway redesign across a wide range of therapy areas. Home therapy programmes for patients requiring intravenous immunoglobulin or subcutaneous immunoglobulin are already available in the majority of immunology centres but not comprehensively delivered. It is recognised that managing chronic conditions outside of the hospital environment improves patients’ quality of life. Utilising homecare for immunoglobulin treatment is vital to deliver the greatest possible flexibility for patients and optimise patients’ control over their condition. At the same time, it allows hospital services to adapt to meet new service demands without creating a burden for community health services. The commissioning and delivery of immunoglobulin treatment should involve a collaborative effort between a number of organisations

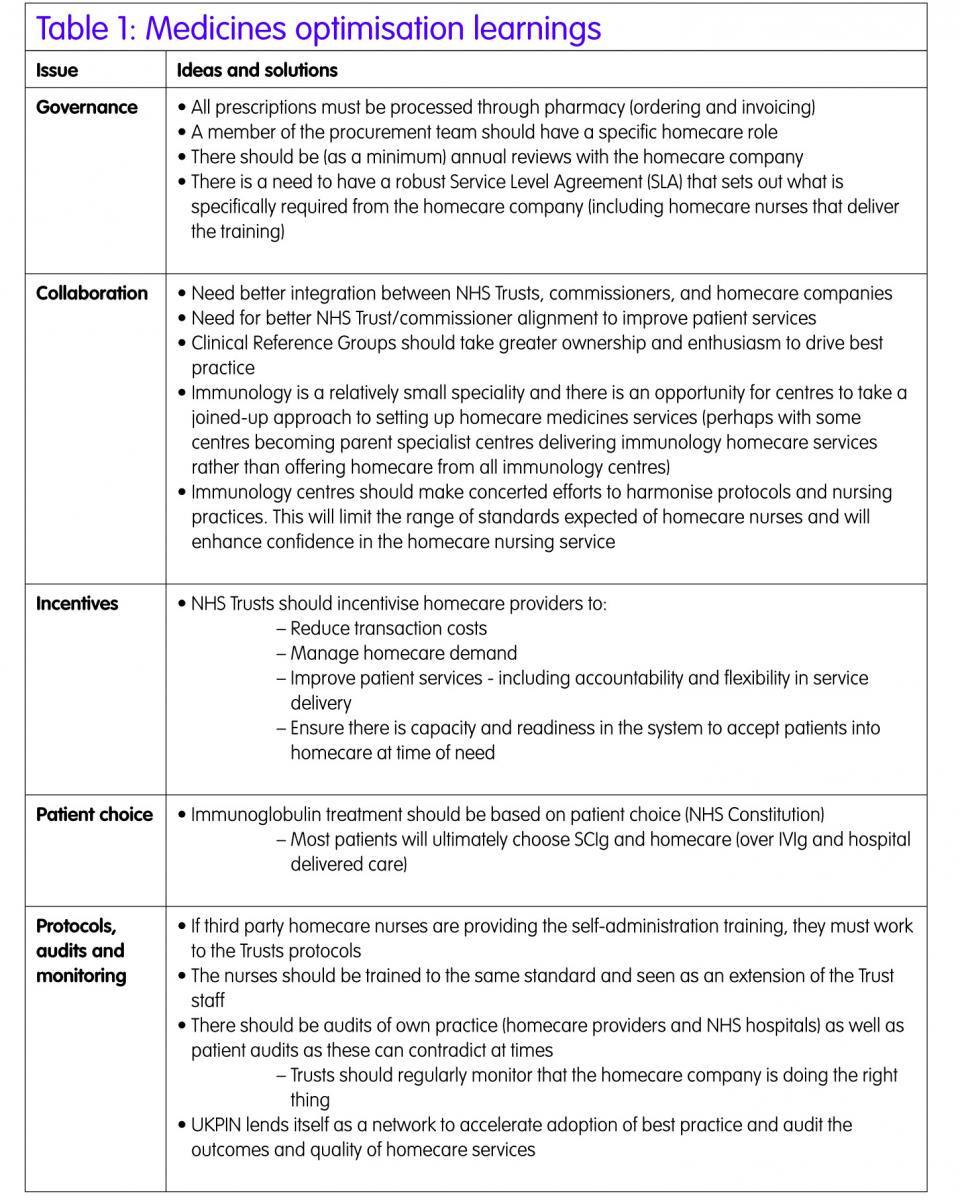

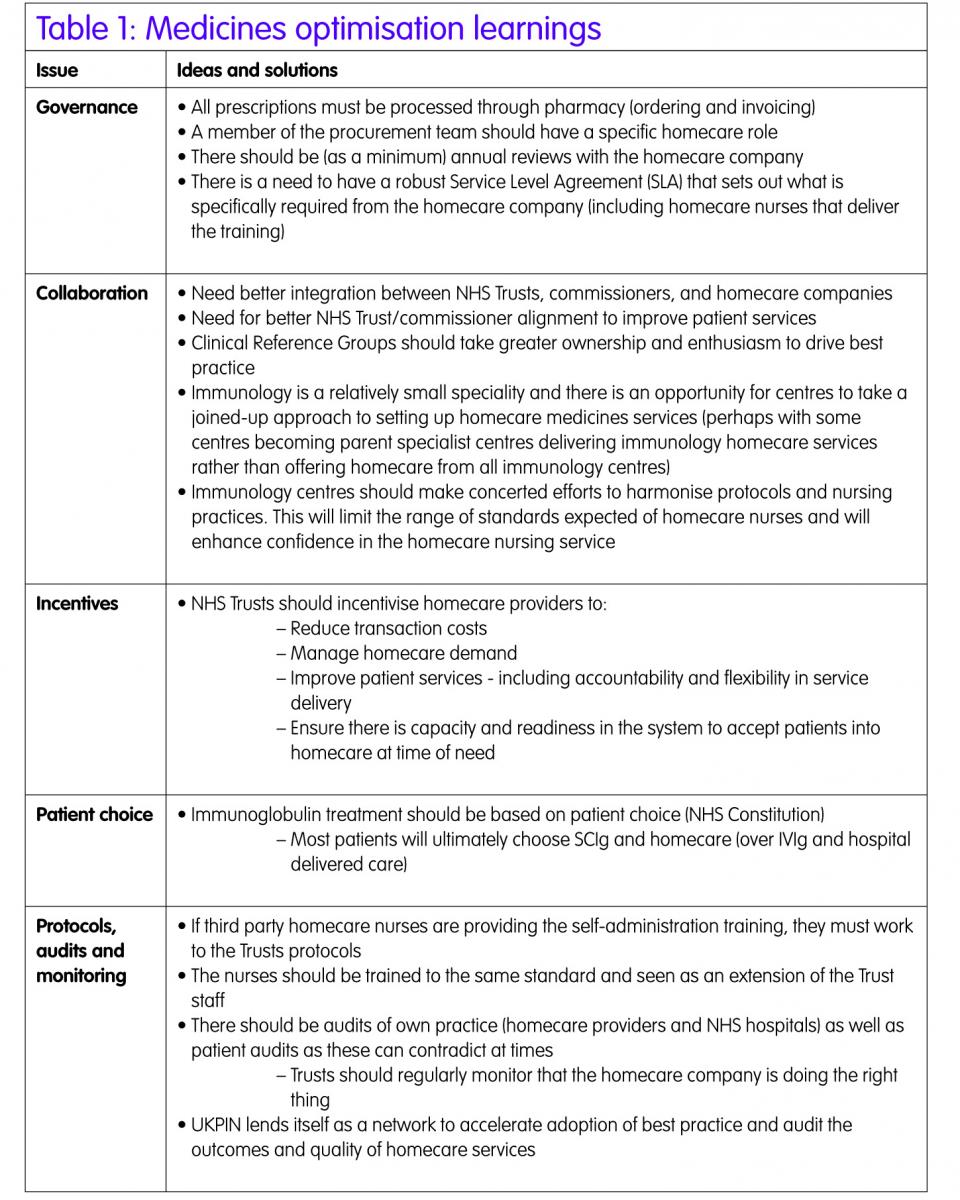

Medicines optimisation: immunoglobulins

In 2011, the Chief Pharmaceutical Officer at the Department of Health commissioned a review of homecare services, which was led by Mark Hackett, Chief Executive of University Hospital Southampton NHS Foundation Trust. The Hackett Report found that the importance of homecare medicines “cannot be underestimated” as the effective delivery of homecare services was helping to ‘transform’ patients’ lives.1 However, he also found that high quality homecare services were the exception, not the rule, and that commercial providers and NHS commissioners needed to redouble their efforts to develop more effective, high-value and, ultimately, safe homecare. The report called for better provider-side leadership, governance and monitoring arrangements, and urged commissioners to work more collaboratively – in partnership with patients – to design optimal homecare services.

The Royal Pharmaceutical Society (RPS) issued its professional standards for homecare services in England in September 2013.5 The standards, developed with the Homecare Standards Workgroup and overseen by the Department of Health Homecare Strategy Board, build on the Hackett Report and are designed to provide a best practice framework for the implementation and delivery of homecare services. They offer clear guidance for teams commissioning and providing homecare services, outlining the standards required to help ensure patients receive a consistent, high-quality and safe homecare experience.

Optimising the opportunity of homecare services will undoubtedly rest on three core areas. First, the homecare providers’ ability to improve the quality of their services. Second, and equally, commissioners’ (and even pharmaceutical companies’) ability to discern between a sub-optimal and best practice provider, in order to determine the sustainable success of the homecare model. Thirdly, the capacity of the commercial homecare providers to accommodate the demands of secondary care providers. SCIg is more easily self-administered at home than IVIg and has a lower incidence of adverse effects relating to peak immunoglobulin levels.6 This may have substantial health economic benefits in terms of hospital and resource saving, and patient quality of life. Hospitals should strongly consider early adoption of IVIg to SCIg switches, or initiation of therapy using SCIg products to guide patient care into the homecare model as soon as is feasible for eligible patients.

The Handbook for Homecare Services in England was published in May 2014.7 The handbook aligns with the RPS Professional Standards for Homecare Services and aims to aid implementation. It includes information and guidance, signposts and identifies key documents that will help homecare teams manage services within a clear professional framework set out in the Society’s Standards. Homecare teams are encouraged to use professional networks and share best practice to enable the continual improvement of homecare services. As an example, UKCPA neurosciences specialist pharmacists regularly share their experiences of new multiple sclerosis homecare services, which is helping to shape national approaches to this burgeoning area.

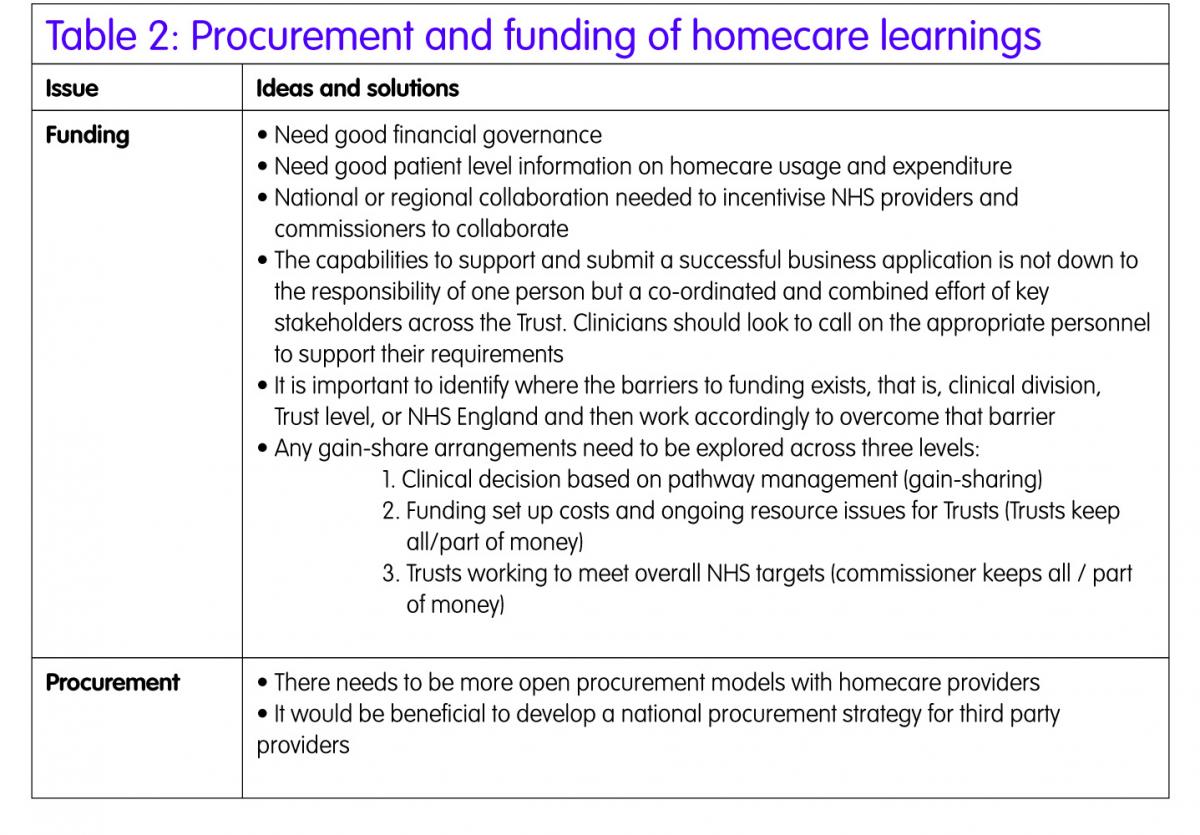

Procurement and funding of homecare

Under the backdrop of current NHS financial constrains and with some acute Trusts facing a significant shortfall in income, certain services models are no longer viable or sustainable. Trusts will need to transform and streamline services, becoming leaner organisations and consider lending themselves to merged services. The commissioning landscape is also changing with greater commissioning responsibility transferring to Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs), particularly primary care, and to some degree specialised services too. NHS England currently has four regional teams responsible for commissioning specialist services and these teams will be responsible for gain-sharing agreements between commissioner and provider.

Current commissioning arrangements for home therapy services are complex and tend to reward hospital-based care. Some progress has been made in ‘gain-sharing’ agreements, whereby NHS commissioners and NHS Trusts share cost savings from implementation of homecare services, enabling Trusts to invest in the development of appropriate governance and operational systems. Immunoglobulin therapy is amenable to various product, dosing and service delivery strategies for the benefit of the NHS.

Conclusions

The benefits of developing homecare services for patients requiring long-term immunoglobulin treatment are clear. Cost–efficacy is central: reduced hospital episodes (avoidance of day case admissions), reduced transport costs, and VAT savings (where applicable – immunoglobulins are already exempt). Greater patient control over their chronic conditions tends to result in fewer problems and higher adherence to treatment plans. Patients experience major improvements in quality of life, and reduced variation in care and access. In order for this to become reality, the role of the Trust Chief Pharmacists, Medical Directors and Nurse Directors need to strengthen around homecare services, internal Trust governance systems need improvement, and better integration is needed between NHS Trusts, commissioners and homecare providers. Homecare services need to be seen as part of the local health system strategy with clear governance, funding and procurement arrangements in place to deliver an optimal homecare service and value for the NHS.

Key points

- Demand for medicine homecare services are rising at an estimated 20% a year and predicted to accelerate further.8

- Trusts offering specialist immunology services should consider harmonisation of practice where practical, potentially with only a few parent centres managing homecare for these patients.

- Having an overarching homecare strategy at a Trust level would improve efficiencies (contracting arrangements with third party providers and sharing resources across clinical departments).

- There should be one national specification for commissioning arrangements regarding homecare medicines services to reduce variations in practice.

- Need to ensure proper audits and regular reviews are in place in order to monitor that an effective service is being provided to patients – including compliance with the clinical pathway.

- Experience and capability to submit successful business cases due to lack of clarity and transparency of funding routes and experience.

- Clarity from NHS England for secondary care providers regarding the consistent application of gain-sharing models.

References

- Hackett M. Homecare medicines, towards a vision for the future. Department of Health, 2011. Gateway reference 16691.

- NHS England. Patient Safety Alert. Minimising risks of omitted and delayed medicines for patients receiving homecare services 2014. Publications Gateway Reference: 01491: Alert reference number: NHS/PSA/W/2014/007.

- Ozerovitch L. Subcutaneous immunoglobulin therapy at home. Nurs Times 2013;109(49/50): 20–21.

- NHS England. Productivity & Efficiency Handbook2013/14. [2012].

- The Royal Pharmaceutical Society. Professional Standards for Homecare Services in England. 2013

- Robert D, Hadden M, Marreno F. Switch from intravenous to subcutaneous immunoglobulin in CIDP and MMN: improved tolerability and patient satisfaction. Therapeutic Adv Neurol Dis 2015;8(1):14–19.

- The Royal Pharmaceutical Society. Professional Standards, Handbook for Homecare Services in England. 2014.

- Hackett M. University Hospital Southampton NHS Foundation Trust 2012: Gateway reference 18170. www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/213144/National-Homecare-Medicines-Review-and-Implementation.pdf (accessed 15 December 2015).