Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a high-risk chronic condition putting patients at risk of a number of potential complications if not managed appropriately.

Emergency departments (EDs) are often ill-equipped to reconcile and continue vital medications for PD, and dramatic deterioration in symptoms and increased morbidity may occur as a result. The role of pharmacists in early reconciliation in this high-risk patient group is not fully explored in the current literature.

Methods

A retrospective audit was conducted identifying all patients passing through Nottingham University Hospitals ED for inpatient stays. Missed doses of anti-Parkinson’s medications were identified both in the ED and the first 24 hours of base ward level, and the effect of an early pharmacist medicines reconciliation, supply and handover was evaluated. Length of inpatient stay, and occasions of actual deterioration of symptoms within the department were also collected.

Results

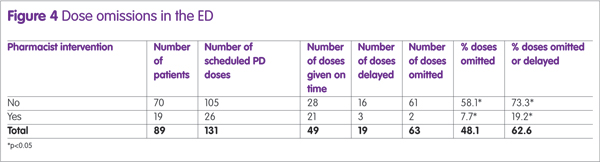

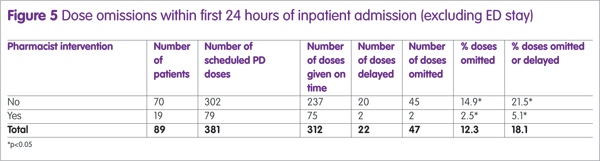

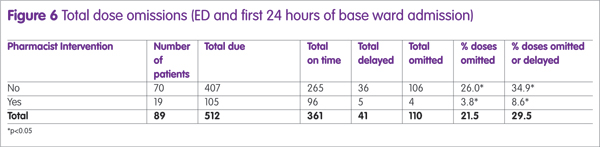

Statistical significantly lower amounts of missed or delayed doses were observed in patients who had early pharmacist intervention in ED, both during patients’ wait in the ED (19.2% vs 72.3%, p<0.05) and their first 24 hours as inpatients (8.6% vs 34.9%, p<0.05). Patients who had an early pharmacist intervention had a lower incident of deterioration of PD symptoms while in the ED. No significant difference was found in patients’ length of stay.

Conclusion

Pharmacists have a vital role in early identification and reconciliation of medications in PD patients and this has the potential to prevent deterioration and prevent further morbidity in this patient profile. This study was limited by a relatively small population number and retrospective methodology and further larger scale studies are needed to fully quantify potential benefits.

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a progressive mobility disorder caused by destruction of dopaminergic neurones within the central nervous system. A considerable body of evidence is available that demonstrate patients with this disease are at high risk of complications1,2 such as falls or collapses,3 septic infections,4 and dysphagia leading to aspiration,5 as well as high risks of deterioration of mobility and functionality requiring secondary care input.

Timely availability and administration of anti-parkinson’s medications (APMs) has been highlighted by both Parkinsons UK6 and the National Patient Safety Association (NPSA)7 as a key implementation in preventing further morbidity in this patient group in secondary care.

EDs are acknowledged to be high risk areas for medication error8–10 with dose omissions of critical medications (including APMs) being highly prevalent.11 Furthermore, considering the current stress on National Health Service (NHS) EDs, patients experience considerable waits both to be seen and a for transfer to base ward level if required. The Royal College of Emergency Medicine, in a statement in 2014, explained that around 500 deaths within EDs could be attributable to overcrowding.

Higher-risk medical patients, including patients with PD, have previously been found to experience longer waiting times in the ED and longer total inpatient stays than other patient populations.12

The clinical presence of pharmacists within inpatient areas in improving quality and safety is now well established.13 Pharmacists are identified as key healthcare professionals in improving medicines optimisation within secondary care. Lord Carter14 was also keen to identify the importance for new and innovative practices required in EDs, to support patient safety and aid with flow.

A preliminary service evaluation15 of a pilot pharmacy service in the ED established the important potential for clinical pharmacy services to prevent dose omissions and improve safety in patients with PD within a large teaching hospital ED. A total of 52 ‘serious’ interventions were recorded over the service period, specifically in relation to APMs (8.8% of the total interventions recorded). Further literature16 explored the potential benefits of clinical pharmacy services in the ED, finding them equally effective at improving safety and quality, as well as reducing ED clinician workload.

This follow-on hypothesis generating study will identify the prevalence of APM dose omission within a large teaching hospital ED, and determine the effect of pharmacist intervention in the care of these patients within the emergency department prior to admission to the ward. We will further explore the role of a pharmacist clinical intervention in these patients, and aim to assess any impact on their care, particularly in the case of missed doses.

Methods

A retrospective audit was designed, in order to capture all patients with PD presenting to Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust Emergency Department between 1 June 2016 and 31 July 2016.

All patients were included who had a formal diagnosis of PD at the time of presentation to the ED and took at least one medication directly used to treat PD. Patients who were discharged directly from the ED (that is, did not require an inpatient stay) were excluded.

Patients with PD were determined by free text search through electronic records of all presentations between these dates. Key word searches for any presence of ‘Parkinsons’, ‘Parkinson’s’, ‘Parkinsonsism’, ‘Sinemet’, ‘Madopar’, ‘Co-Beneldopa’, ‘Cobeneldopa’, ‘Co Beneldopa’, ‘Co-Careldopa’, ‘Cocareldopa’, Co Careldopa’, ‘Rotigotine’, ‘Stalevo’, ‘Amantadine’, ‘Rasagaline’ and ‘Selegeline’ were included for further analysis.

Cases identified were then reviewed by a research pharmacist and/or research ED clinician for inclusion under the aforementioned criteria.

For all included cases, the total doses due within ED and the first 24 hours of inpatient admission were collected. This was determined against expert medicines reconciliation by inpatient pharmacists (which was regarded as gold standard). All ED documentation (including drug charts, temporary charts and electronic notes) were reviewed for documentation of medications being administered, delayed or omitted. A lack of documentation was regarded as an omission. Further data around deterioration of symptoms after admission to ED, whether APMs were prescribed in ED, and errors in prescribing APMs were also collected.

Intervention by a pharmacist within the ED, defined by review and confirmation of primary drug history, supply (or prompted administration) of medication and ward handover was also collected for all patients. A single pharmacist was available during the service period, working 07:30-15:30 during weekdays.

Statistical analysis was conducted using Microsoft Excel 2010.

Results

A total of 177 patient records were returned from the key word search, 62 patients were excluded because they were either discharged directly from the ED or did not wait for treatment.

A further 23 patients were excluded as records indicated they did not suffer from PD. Lastly, three patients were excluded because complete records were unavailable for analysis; this left a total of 89 patients who met the inclusion criteria and for whom records were available for analysis.

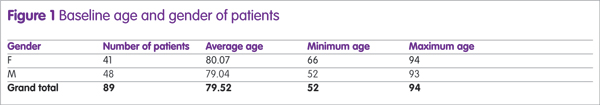

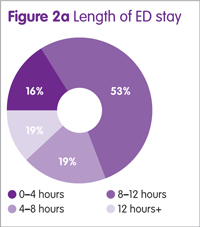

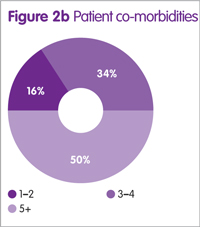

Baseline characteristics (age and gender) were approximately similar in the analysis groups (Figure 1). A total of 84% of patients had at least three documented co-morbidities, with 50% having greater than five (Figure 2a and 2b).

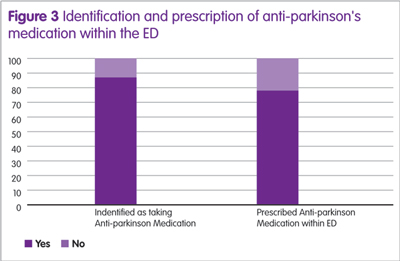

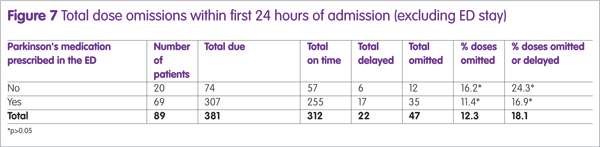

A total of 86.5% of patients were correctly identified within medical clerking in the ED as having PD, and taking oral therapy for the condition; 77.5% were actually prescribed these APMs within the department (Figure 3).

Pharmacist intervention as outlined in the Methods section occurred in 19 of the 89 cases (21.3%). The mean numbers of doses required per patient were similar in both groups.

Omitted doses

Dose omissions and delays within the ED were considerably higher in patients who did not have an early pharmacist intervention (Figure 4). This effect was also extended to dose omission and delays on base ward level within the first 24 hours (Figures 5 and 6). The ED pharmacist intervention demonstrated a statistically significant reduction in dose omissions and delays, both while patients were waiting within ED, and also at base ward level.

Further analysis around prescribing of APMs within ED, demonstrated an impact on the number of dose omissions at base ward level within the first 24 hours of inpatient stay (Figure 7). Although a lower percentage of doses were either delayed or omitted, the difference was not statistically significant (p>0.05).

Length of stay

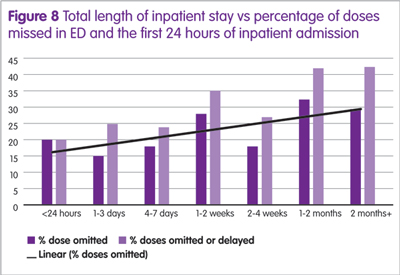

The mean length of stay for patients who did not receive pharmacist intervention in the ED was 10 days, which was similar to a mean of 11 days in patients who had a pharmacist intervention. However a trend was observed where generally longer inpatient stays were found in patients who had a higher percentage of missed doses in the first 24 hours of inpatient stay combined with their ED stay (Figure 7). This trend was not found to be statistically significant.

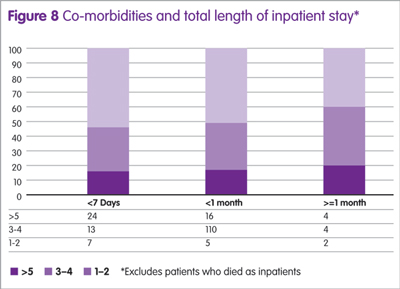

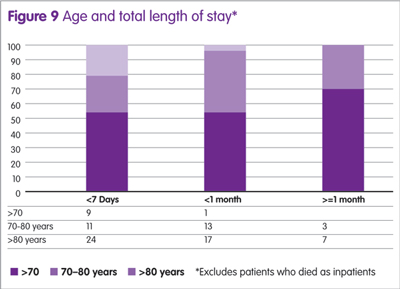

No particular trend was observed when total length of inpatient stay was plotted against the number of co-morbidities recorded for the patient (Figure 8). The relative numbers of co-morbidities patients suffered remained at a consistent percentage irrespective of total length of stay. Age may be associated with risk of prolonged stay (Figure 9), with only 10% of patients under the age of 70 spending more than seven days as an inpatient, compared with 53.3% over the age of 70.

Deterioration within the ED

All cases were also assessed for deterioration of clinical PD symptoms (as defined by increased stiffness, swallowing difficulties or reduced mobility from baseline) in the admitted patients. There is documented clinical worsening of PD symptoms for ten patients while in the ED. None of these cases involved a pharmacist intervention. In all ten cases, patients had at least one dose omitted in ED.

Medication prescribing errors were detected in a total of 16 cases where APMs were prescribed in the ED. These errors related to inappropriate dose, frequency or formulation of the medication.

A further four of these cases that had pharmacist intervention had errors corrected immediately, with patients not receiving any incorrect doses.

Discussion

The results demonstrate the potential impact of a consistent pharmacy presence on this high-risk population of patients. Furthermore, these findings lend weight to previous studies highlighting EDs as high-risk environments. Lastly, clear risk has been identified of patients deteriorating from baseline as a result of delayed medicines reconciliation within ED.

Baseline demographics and admissions

A total of 151 patients were identified and analysed who suffered from PD throughout the two-month study period. Of these, 89 (58.9%) required inpatient admission. This figure more than doubles the approximate average percentage internally of all patients who require inpatient treatment (26%). The average age of approximately 80, reflects a considerably older population of patients suffering from PD.

This finding is generally consistent with literature, considering patients suffering from PD typically are older, and are at higher risk of both medical and traumatic injuries.

Deterioration within the ED

A total of 62.6% APM doses were missed within the ED with no clinical reasoning, which demonstrates extremely poor compliance with internal guidance on continuation of time-critical medications, as well as national guidance.7 This figure is consistent with a similar previous study,17 which found a 74.6% dose omission rate at another acute hospital Trust, indicating the problem may not be isolated to individual EDs and may be explained by systems failures. This may be due to compounding factors in the ED such as time pressure, overcrowding, lack of awareness of missed APMs and other priorities set by clinicians focusing on treatment of the presenting complaint – rather than maintenance of chronic therapies.

As previously discussed,18-20 APM omissions can be associated with potentially rapid and severe deterioration in symptoms. These are of particular concern in secondary care owing to development of dysphagia, potentially leading to aspiration, and mobility reduction increasing the likelihood of falls. Of the cases reviewed, clear documentation was found in ten cases (11.2%) where omissions may have lead to clinically significant deterioration of symptoms. These situations occurred exclusively in patients who did not have pharmacist review.

Decisions to admit may have been influenced by these deteriorations in conjunction with pathogenic disease, and caused extensions in inpatient stay as a result.

Impact of the pharmacist in the ED

Pharmacist intervention occurred in 21.3% of the cases examined. This figure could be expected considering the level of service provision, which equates to 37.5 hours per working week, and that pharmacist responsibilities would have also extended to other high-risk patients. Pharmacists’ skill sets are well suited for this particular role, and would likely be superior to either a nurse- or medic-led approach to identifying and prioritising PD patients, due to innate knowledge of dosing schedules, formulation substitutions and rapid sourcing and supply.

Pharmacist intervention was associated with statistically significant reduction in dose omissions while in the ED and within the first 24 hours of inpatient admission. The effect within the ED can be explained by pharmacists identifying patients as high-risk at an early stage, having APMs prescribed and supplied and implementing treatment plans while in the ED. Thus, prescribing, supply and administration of APMs are all accelerated.

This approach has a completely different prioritisation strategy to typical ED processes.

The effect was not expected to be as profound at a ward level; however, data clearly demonstrate dramatic reductions in dose omissions after transfer from ED to base ward. This effect at base ward level is potentially explained by the improved handover and continuity of care that a pharmacist can provide in regards to medication supply and documentation of checked medication regimes. It was also noted from the results that a reduction in dose omissions (although not statistically significant) was observed in patients who had regular APMs prescribed within ED against those who did not. Patients might experience extended base ward waits prior to medical clerking which, when combined with omission in the ED, can lead to considerable proportions of time before normal medication can be reconciled and given.

It was, however, important to note that pharmacist intervention was unable to eliminate dose omissions. This is likely explained by pharmacists identifying patients once doses had already been missed in the department, and relying on nurse administration of medications by prompting rather than administering themselves.

These data indicate a tangible benefit in patient care and a clear prevention of deterioration within the department facilitated by early pharmacist intervention. These included two cases where patients attended the ED unable to resume oral therapies due to acute illness, where pharmacists rapidly recommended alternative measures to allow symptom control. Deterioration was not detected in these patients whilst in the department. These early deteriorations in PD symptoms which were excluded by previous studies may play important roles in preventing hospital admission, and as this study was not designed to assess this, further work might be required.

Length of inpatient stay

No conclusive effect was observed in regards to a reduction in inpatient stay in this study. A visual trend was observed where a higher percentage of dose omissions were observed in patients who were admitted for longer, though no statistical significance can be determined from these results.

Furthermore, no particular relationship was observed between more co-morbidities and increased length of stay. There was a noted potential relationship between increased age and longer length of stay, with a higher percentage of patients over the age of 70 requiring inpatient stays of over seven days.

A recent study18 found that a specialist PD unit within secondary care reduced APM omissions, increased timely administration and, importantly, demonstrated a reduced length of stay compared with other non-specialist ward areas. The specific effect of the number of dose omissions on the total length of stay was also explored in another hospital19 finding a significant increase in length of stay in patients who had a delay or missed at least one APM dose. These studies demonstrate potentially drastic implications on patient safety in secondary care, as well as financially in terms of reduced admissions lengths and flow through hospitals.

A recent larger scale study20 was conducted to determine the effect of delayed administration of APM on total length of stay. Ultimately the study did not demonstrate a statistically significant relationship between dose omissions and length of stay. Despite the lack of an association, the authors were keen to highlight that dose omissions were still detrimental to the best patient care. It was notable, however, that all studies included inpatient areas only and made no analysis of patient’s assessment and stay within EDs. A short retrospective audit17 examined APM omission and found 76% of patients experienced delays or omissions during attendances to the ED. An important and highly relevant discussion point from this study was raised around how poor medicines reconciliation early in the patient’s journey in ED has the potential to cause extended inpatient stays and poorer outcomes. Very little literature is available exploring this effect.

APM vs other time critical medications

Prompt identification of patients suffering from PD and requiring continuation of their therapies was identified as a key limiting factor in preventing dose omissions. Compared with other time critical medications explored in our previous analysis,15 APMs have relatively few clinically justifiable acute contraindications to their use. This differs considerably from insulin or anticoagulants, for example, where the diagnostic process within the ED can require specialist clinical consideration and potentially be more clinically justifiable to temporarily suspend treatments.

This may partly explain how pharmacists might have such a high impact in these patients within the ED, considering the main adjustment to therapies made acutely were to convert formulations in light of swallowing difficulties or convert to dopamine agonist patches because of the clinical decision for a patient to be kept nil by mouth. Both of these interventions are typically regarded as requiring specialist clinical pharmacist input, which was not only readily available in this case, but actively provided and prioritised.

Limitations

The methodology of this study has several limitations, the key being the relatively small sample size. This sample size does not provide enough data points to generate statistical power to prove a hypothesis, and thus this study was described as hypothesis generating.

Data gathering by free text keyword search may exclude a population of patients who had not been documented as having PD, and thus patients identified may be an underestimation. Furthermore, the methodology in this study assumed no documentation as an omission, whereas patients might have actually taken their own medication while in the department. Equally, when doses were signed administered, these were assumed to be given on time, where poor practice of not documenting the time administered might have changed these occasions into delays.

Information around the severity of the presenting complaint was not taken into account, because the spectrum of the acute presenting complaint might affect the ability of ED clinicians to prescribe drugs, such as in situations of life-threatening trauma or cardiac arrest. These situations may have more close correlations with dose omissions, rather than pharmacist intervention. Furthermore, situation of admission may also more significantly affect a total length of inpatient stay.

Conclusions

Pharmacist intervention was associated with a statistically lower number of omissions of APMs while in the ED. This intervention was associated with a lower incidence of PD-related deterioration in symptoms while in the department. Furthermore, as the interventions involved early medicines reconciliation, supply and handover of care, beneficial effects on dose omissions were observed on base ward level also.

These results also clearly demonstrate the potential deficiencies of EDs in reconciling and continuing chronic therapies in the acute setting. Readily available clinical pharmacists are an ideal choice in taking on this responsibility and taking pressure off ED clinicians, as well as yielding time and efficiency savings on base ward level.

The relatively small amount of data collected makes it difficult to comment on conclusions around an effect on length of patient stay. It is likely that a combination of factors such as age, co-morbidities and presenting complaint has impacts on length of stay and outcomes, and greater numbers of patients would need to be analysed to draw concrete conclusions.

Further study is required in exploring clinical pharmacy services within EDs on other high risk patient profiles, to determine if similar benefits can be identified.

References

1 Gerlach O et al. Deterioration of Parkinson’s disease during hospitization: Survey of 684 Patients. BMC Neurology 2012:12:13.

2 Guttman M et al. Parkinsonism in Ontario : Comorbidity associated with hospitalization in a large cohort. Mov Disord 2003;17:45–54.

3 Wood B et al. Incidence and prediction of falls in Parkinson’s disease : a prospective multidisciplinary study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2001;72:721–5.

4 Haddad S et al. Prognostic factors associated with short-term decompensation of sepsis in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med 2014;21(5).

5 Fernandez H, Lapane L. Predictors of mortality among nursing home residents with a diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease. Med Sci Monit 2002;8:241–6.

6 Parkinsons Disease Society. Emergency management of patients with Parkinson’s. (accessed December 2017).

7 National Patient Safety Association (NPSA). Reducing harm from omitted and delayed medication in hospital. www.nrls.npsa.nhs.uk alerts/?entryid45=66720 (accessed December 2017).

8 Sin B et al. Implementation of a 24-hour pharmacy service with prospective medication review in the emergency department. Hosp Pharm 2015;50(2):134–8.

9 Rothschild J et al. Medication errors recovered by emergency department pharmacists. Ann Emerg Med 2010;55(6):513–21.

10 Stasiak P et al. Detection and correction of prescription errors by an emergency department pharmacy service. CJEM 2014;16(3):193–206.

11 Marconi G, Claudius I. Impact of an emergency department pharmacy on medication omission and delay. Paediatric Emerg Care 2012;28(1):30–3.

12 Gohil.K. ED and Inpatient waiting times for higher risk medical patients. Internal Audit, Nottingham University Hospitals;2016.

13 Kaboli P et al. Clinical pharmacists and inpatient medical care: a systematic review. Arch Intern Med 2006;166(9):955–64.

14 Lord Carter of Coles. Operational productivity and performance in English NHS Acute Hospitals: unwarranted variations. (accessed December 2017).

15 Gohil K, Patel C, Sani. M. Integrating a clinical pharmacy service in the ED. Hospital Pharmacy Europe 2016;83. (accessed online 10/3/17).

16 Henderson K, Gotel U, Hill J. Using a clinical pharmacist in the Emergency Department. EmergMed J 2015;32(12):RCEM Abstract 045.

17 Magadalinou K, Martin A, Kessel B. Prescribing medications in Parkinsons disease (PD) during acute admissions to a District General Hospital. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2006;13:539–40.

18 Skelly R et al. Does a specialist unit improve outcomes for hospitalized patients with Parkinson’s Disease? Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2014;20:1242–7.

19 Martinez-Ramirez D et al. Missing dosages and neuroleptic usage may prolong length of stay in hospitalized Parkinson’s disease patients. PLoS ONE 2015;10:e0124356.

20 Skelly R, Brown L, Fogarty A. Delayed administration of dopaminergic drugs is not associated with prolonged length of stay in hospitalized patients with Parkinson’s Disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2017;35:25–9.