JC Kaski

MD DSc FRCP FESC FACC

Professor of Cardiovascular Science

Department of Cardiological Sciences

St George’s Hospital Medical School

London, UK

E:[email protected]

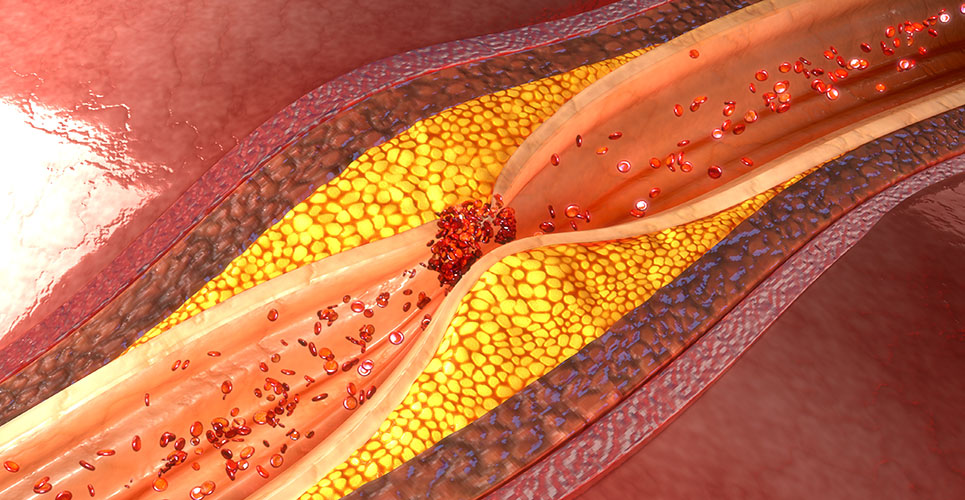

A number of studies in recent years have confirmed that inflammation plays a major role in atherogenesis and the development of coronary artery disease (CAD).(1) Moreover, inflammatory mechanisms appear to be responsible for the disruption of atheromatous plaques, which often lead to the development of acute coronary syndromes (eg, unstable angina and acute myocardial infarction).(2) Inflammation triggers endothelial cell activation, which in turn facilitates the infiltration and accumulation of monocytes in the arterial intima.(1) It has been shown that activated endothelial cells express leucocyte adhesion molecules at atheromatous sites: for example, vascular cell adhesion molecules (VCAM-1s) and monocyte chemoattractant proteins (MCP-1s).(2,3) These and other molecules stimulate and facilitate the interaction between endothelial cells and circulating inflammatory cells, thus initiating or accelerating the atherosclerotic process.

The coronary arteries of patients with risk factors, or established atheroma, show an increased production of chemoattractant proteins, cytokines and reactive oxygen species that further exacerbate the inflammatory process.(2) For example, oxidised low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, a major pathogenic mechanism of therosclerosis, increases the expression of VCAM-1s and MCP-1s.(3,4) Although oxidised LDL is an established inflammatory stimulus, the presence of increased levels of oxidised LDL does not explain all incident cases of CAD or unstable angina. The mechanisms that do trigger the inflammatory process underlying CAD have not yet been categorically defined but are likely to be multifactorial. Recently it has been proposed that chronic infections by viruses and bacteria may play a substantial role in both atherogenesis and rapid CAD progression.(5) The infectious hypothesis of CAD is rather old,(6) but its revival in recent years has been stimulated by findings of seroepidemiological studies(5) and the intriguing results of antibiotic trials.(7,8)

Chronic infection in the pathogenesis of CAD

Following the initial report by Saikku et al. in 1998 of an association between antibody titres against the Gram- negative bacterium Chlamydia pneumoniae (CPn) and both CAD and myocardial infarction,(9) several authors have investigated the association between infection and atheromatous disease. As a result, bacteria such as CPn, Helicobacter pylori (HP) and Porphromonus gingivalis, among others, have been implicated in atherogenesis.(10) Similarly, viruses such as cytomegalovirus (CMV) and herpes simplex virus (HSV) have also been postulated to play a role.(10) CPn in particular has been suggested to contribute to both atherogenesis and rapid CAD progression. This suggestion has been endorsed by seroepidemiological findings, the observation that active forms of CPn can be found in atheromatous tissue, and the finding in experimental animals that CPn inoculation induces or accelerates atherosclerosis.(11) Moreover, results of antibiotic studies in both patients and experimental animal models provide further support to the potential association between CPn and CAD.(5)

An association has been reported between atherogenesis and CMV infection in patients who undergo cardiac transplantation, and between HSV-1 and cardiovascular events.(12) In a prospective, nested, case-control study of individuals aged >65 years, Siscovick et al. found that nonfatal myocardial infarction and cardiovascular death were more frequent among subjects with positive IgG antibodies against CMV-1 compared with those with negative titres.(12) The enthusiasm triggered by the initial studies that reported a significant association between CPn and CAD has been tempered by recent prospective clinical and animal investigations which failed to confirm such an association. (13–16)

Antibiotic trials

As a logical consequence of the positive sero-epidemiological findings and results of animal studies, several antibiotic trials have been carried out in patients over the past five years. The first antibiotic study performed in CAD patients was conducted in our institution from 1995 to 1996 and published in 1997.(7) This study assessed 220 patients with a history of myocardial infarction, of whom 68 with positive antibody titres against CPn were randomised to receive either placebo or azithromycin. The study showed that seropositive patients in the placebo group had a fourfold increased risk of developing cardiac events compared with seronegative patients. Moreover, seropositive patients treated with azithromycin had a similar rate of events as placebo seronegative patients. Antibiotic treatment improved markers of inflammation (ie, monocyte tissue factor and integrin CD11b) and reduced CPn IgG titres. The clinical observations of this small pilot trial were endorsed by findings in the ROXIS (ROXIthromycin in non-Q-wave coronary Syndromes) study.(8) In the ROXIS pilot study, 202 patients with unstable angina were randomised to receive oral roxithromycin (150mg twice daily) or placebo for 30 days. The study showed a statistically significant reduction in clinical events (composite endpoint: death, myocardial infarction and severe recurrent angina) at day 31 of follow-up.(8) The beneficial effects, however, were no longer significant at 180 days.(17)

The results of these two pilot studies contrast with the negative clinical findings reported by the ACADEMIC (Azithromycin in Coronary Artery Disease: Elimination of Myocardial Infection with Chlamydia) investigators.(18) In the ACADEMIC trial, 302 CAD patients, CPn seropositive (>1:16 IgG antibodies), were randomised to azithromycin (500mg/day for three days, followed by 500mg/week for three months) or placebo.(18) At six months, azithromycin and placebo patients had similar rates of clinical endpoints, but inflammatory markers, such as C-reactive protein and interleukin-6, were significantly improved in the antibiotic group compared with placebo.

Similar beneficial effects on inflammatory markers were reported in CAD patients who had antibodies against CPn and HP and were treated with clarithromycin for two weeks.(19) More recently, the STAMINA (South Thames Antibiotic trial in Myocardial Infarction and uNstable Angina) results were presented, which showed that wide-spectrum antibiotic therapy significantly reduced cardiac events during long-term follow-up in patients with acute coronary syndromes.(20) Markers of inflammation were also shown to be improved in patients receiving antibiotic therapy. STAMINA patients were included irrespective of CPn antibody status and were randomised to placebo or one of the following antibiotic regimens:

- Amoxycillin/metronidazole – HP eradication.

- Azithromycin – CPn treatment.

The results of these trials suggest that the beneficial effects seen may be due, at least in part, to an anti-inflammatory effect of antibiotic treatment.(7,8,18–20)

Despite the interesting reports regarding antibiotic treatment of CAD patients, many questions still remain unanswered. Among these, the reason for the positive effects of antibiotics, the duration of treatment and the number of antibiotics required. Several large antibiotic studies are currently in progress (see Table 1), which may help answer at least some of these questions.

[[HPE02_table1_18]]

Conclusion

While the inflammatory hypothesis of atherogenesis is strongly endorsed by recent studies, controversial data are emerging regarding the potential pathogenic role of chronic infection in CAD, which require careful analysis. Antibiotic trials to date seem to indicate that selected groups of CAD patients may derive benefit from this intervention. The mechanism responsible for the beneficial action of these agents needs to be further investigated but appears to involve anti-inflammatory effects. The suggestion by recent studies that multiple infectious pathogens – rather than a single agent – can trigger CAD is important and may have implications regarding antibiotic choice. The infectious theory of atherothrombosis is intriguing and, if a causal or major contributory role of infection is confirmed in CAD patients, this will have major therapeutic implications. At this point in time, however, there is no clinical indication for the use of antibiotics in patients with angina pectoris.

I am grateful to Dr Bodil Als-Nielsen (Cochrane Hepato-Biliary Group, Copenhagen Trial Unit) for providing me with information regarding ongoing trials.

References

- Ross R. Atherosclerosis: an inflammatory disease. N Engl J Med 1999;340:115-26.

- Kaski JC, Zouridakis E. Inflammation, infection and acute coronary plaque events. Eur Heart J 2001;3(Suppl I):110-15.

- Kunsch C, Medford RM. Oxidative stress as a regulator of gene expression in the vasculature. Circ Res 1999;85:753-66.

- Libby P, Egan D, Skarlatos S. Roles of infectious agents in atherosclerosis and restenosis: an assessment of the evidence and need for future research. Circulation 1997;96:4095-103.

- Danesh J, Collins R, Peto R. Chronic infections and coronary heart disease: is there a link? Lancet 1997;350:430-6.

- Osler W. Diseases of the arteries. In: Osler W, editor. Modern medicine: its practice and theory. Philadelphia, PA: Lea and Febiger; 1908:429-47.

- Gupta S, Leatham EW, Carrington D, et al. Elevated Chlamydia pneumoniae antibodies, cardiovascular events, and azithromycin in male survivors of myocardial infarction. Circulation 1997;96:404-7.

- Gurfinkel E, Bozovich G, Daroca A, et al. Randomised trial of roxithromycin in non-Q-wave coronary syndromes: ROXIS pilot study. Lancet 1997;350:404-7.

- Saikku P, Leinonen M, Mattila K, et al. Serological evidence of an association of a novel chlamydia, TWAR, with chronic coronary heart disease and acute myocardial infarction. Lancet 1988;2:983-5.

- Kuvin JT, Kimmelstiel CD. Infectious causes of atherosclerosis. Am Heart J 1999;137:216-26.

- Camm AJ, Fox KM. Chlamydia pneumoniae (and other infective agents) in atherosclerosis and acute coronary syndromes. Eur Heart J 2000;21:1046-51.

- Siscovick DS, et al. Chlamydia pneumoniae, Herpes simplex virus type 1, and cytomegalovirus and incident myocardial infarction and coronary heart disease death in older adults. Circulation 2000;102:2335-40.

- Ridker PM, Kundsin RB, Stampfer MJ, et al. Prospective study of Chlamydia pneumoniae IgC seropositivity and risks of future myocardial infarction. Circulation 1999;99:1161-4.

- Hoffmeister A, Rothenbacher D, Bode G, et al. Current infection with Helicobacter pylori, but not seropositivity to Chlamydia pneumoniae or cytomegalovirus, is associated with an atherogenic, modified lipid profile. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2001;21:427-32.

- Ridker PM. Inflammation, infection and cardiovascular risk. How good is the clinical evidence? Circulation 1998;97:1671-4.

- Aalto-Setälä K, Laitinen K, Erkkilä L, et al. Chlamydia pneumoniae does not increase atherosclerosis in the aortic root of apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2001;21:578-84.

- Gurfinkel E, Bozovich G, Beck E, et al. Treatment with the antibiotic roxithromycin in patients with acute non-Q-wave coronary syndromes. Eur Heart J 1999;20:121-7.

- Anderson JL, Muhlestein JB, Carlquist J, et al. Randomized secondary prevention trial of azithromycin in patients with coronary artery disease and serological evidence for Chlamydia pneumoniae infection: the Azithromycin in Coronary Artery Disease: Elimination of Myocardial Infection with Chlamydia (ACADEMIC) Study. Circulation 1999;99:1540-7.

- Torgano G, Cosentini R, Mandelli C, et al. Treatment of Helicobacter pylori and Chlamydia pneumoniae infections decrease fibrinogen plasma levels in patients with ischaemic heart disease. Circulation 1999;99:1555-9.

- Stone AF, Mendall M, Kaski JC, et al. Abstract: antibiotics against Chlamydia pneumoniae and Helicobacter pylori reduce further cardiovascular events in patients with acute coronary syndromes. JACC 2001;37(2):349A;1185.

- Hansen S, Als-Nielsen B, Damgaard M, et al. Intervention with clarithromycin in patients with stable coronary heart disease. Heart Drug 2001;1:14-19.

- Jackson LA. Description and status of the Azithromycin and Coronary Events Study (ACES). J Infect Dis 2000;181(Suppl 3):S579-81.

- Myocardial infarction intervention trial (WIZARD). J Infect Dis 2000;181(Suppl 3):S573-8.

Resources

European Society of Cardiology

W:www.escardio.org

Cardiology Online

W:www.theheart.org

AMEDEO

The Medical Literature Guide

W:www.amedeo.com

Forthcoming event

5–9 May 2002

World Congress of Cardiology

Sydney, Australia

W:www.wcc2002.com.au