The recruitment and retention of clinical and non-clinical staff is a persistent challenge across secondary care services. Noting a concerning vacancy rate, the pharmacy department at East Kent Hospitals University NHS Foundation Trust set about determining the reasons for this and identifying solutions. Pharmacists Alice Lo and Rebecca Morgan discuss the findings of their flexible working survey and the strategies they’ve implemented to maintain a positive working environment and better support pharmacists in their roles, as well as ensuring safe and effective patient care.

The pharmacy department at East Kent Hospitals University NHS Foundation Trust (EKHUFT) has recently experienced a high vacancy rate, particularly among pharmacists where it stands at more than 20%. In 2022, the vacancy rate was significantly lower. A project was initiated within pharmacy to identify the reasons for this vacancy rate and identify solutions that could be implemented.

Insufficient flexible working was often cited in the Trust staff survey and historically there had been active implementation of this option for staff. At present, over 80% of Band 8a-8c pharmacists have a flexible working pattern in place. As the Trust has recently amended its policy to allow more flexibility, including hybrid working, the pharmacy department wanted to see whether the approach to flexible working was seen as a negative or a positive to recruiting and retaining pharmacists at EKHUFT.

An employee is considered to have a flexible working pattern if they do anything different to the normal working hours. These are 37.5 hours, working Monday-Friday from 9am to 5:30pm with an hour for lunch, plus one in six weekends and a rolling pattern for late nights.

EKHUFT has three in-patient sites, and the majority of staff are based at only one site. However, a significant number are required to attend two or three sites each week. The sites are, on average, an hour’s drive apart and there is limited suitable public transport in this part of the country.

Method and results

A survey was created on SurveyMonkey for pharmacists to share their views of their current flexible working pattern, if they had one, and how the pharmacy department could improve the options.

Demographics

The survey was sent to 70 pharmacists, which corresponded to 62 whole time equivalent (WTE) pharmacists due to a number of part time staff. This was the number of staff in post at that time as there were a number of vacancies in the department.

There were 37 responses received from the total of 70 survey recipients. One respondent was a Band 5 and therefore their responses were excluded from the analysis as they may not have been a qualified pharmacist.

Of the 36 respondents analysed, most were at Band 7 (See Figure 1). There were four Band 6 respondents and 14 Band 7 respondents (51% together). Band 8 had 17 respondents, while 12 respondents were at Band 8a and there were two each at Band 8b and 8c. One respondent did not give their banding.

Most respondents had been in the Trust for between two and five years (54%) and almost a third (31%) over five years (Figure 2).

Flexible working policy and flexible working pattern

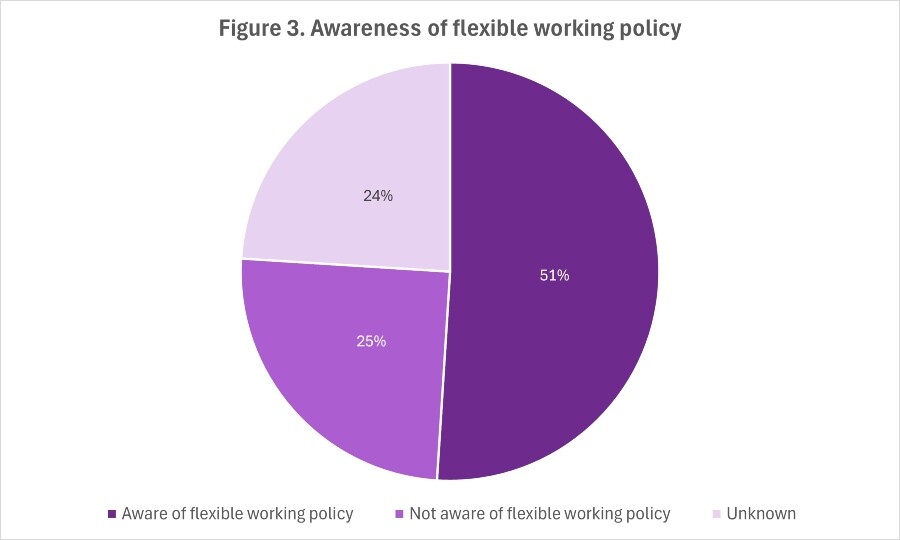

Over half of the respondents (51%) were aware of the flexible working policy (Figure 3). A quarter said they were not aware of the Trust’s flexible working policy (25%) and these respondents ranged from Band 6 to 8a, although most were Band 6 and 7 and two were Band 8a.

Some 11% (n=4) were on a flexible working pattern that was agreed on recruitment, and 34% (n=12) were on a flexible working pattern agreed once in post (Figure 4). One of these respondents answered both ‘am on a flexible working pattern that was agreed on recruitment’ and ‘agreed once in post’. Therefore, 43% of respondents (n=15) were on a flexible working pattern.

Of the 15 respondents on a flexible working pattern, one was a Band 6 in post less than a year, three were Band 7 and in post between two and five years. The remaining 10 respondents (67%) were in Band 8 and had been in post for less than a year to over five years.

Satisfaction with current working pattern

A total of 71% of respondents (n=25) said they were happy with their current working arrangements, while the remainder (29%, n=10) answered that they were not happy.

The respondents who were not happy with their current working patterns were a mixture of bands from Band 6 to 8a, with half of these respondents being Band 7. Three respondents have since applied for and are now on a flexible working pattern.

Five respondents were not aware of the Trust flexible working policy, although one of these is on a flexible working pattern. One respondent was recently made aware of the policy and although they have not yet applied, they will in the near future.

The reasons for respondents not being happy with their current working arrangements included travel time; wanting a day off in the week; having limited work-life balance; and wanting flexible working, although they didn’t mention in what pattern.

The reasons respondents who were on a flexible working pattern but not happy with their current arrangement were because the hours were too rigid, wanting to finish early for school pick up and having to take part in late nights and weekends.

Of the 21 respondents who were not on a flexible working pattern, two had previously applied. Of the 19 respondents who had not previously applied for flexible working, 17 answered the question ‘What are the reasons stopping you from applying for flexible working’. Two respondents stated that it was ‘not applicable’. This could be interpreted as flexible working is not applicable to the respondent.

One respondent stated that they ‘Did not want to be on lates everyday’. Four respondents did not want or require flexible working. One of these respondents also thought service needs would not allow it. Four respondents did not think their requests would be approved, including two who stated that it was due to service requirements. Two respondents had not previously thought about flexible working, and three respondents said they did not know what it was or how to apply.

Benefits of flexible working

Some 91% of the respondents (n=32) answered the question regarding the benefits of having a flexible working pattern (Figure 5). The benefits to staff that were listed were that flexible working gives a better work life balance, provides better time management for personal needs and caters for childcare needs. There is less chance of burnout, shorter commuting times and fewer distractions at home, so staff are more productive. Respondents also said they felt more productive while at work when on a flexible working pattern.

When it came to team benefits, there was better use of the limited office space in the pharmacy department and staff felt more motivated. Respondents were also more productive as they were able to work outside of normal working hours, and they were less distracted. One respondent stated that they take less unpaid leave as a result of the flexible working pattern.

Patient benefits included staff being able to adjust working times to their workload during the day and staff being available for longer working hours.

Negative impacts of flexible working

A total of 83% of respondents (n=29) answered the question regarding the negative impacts of having a flexible working pattern (Figure 6). Five respondents stated there were no negative impacts of flexible working. Two stated it was difficult to accommodate flexible working for everybody as some hours and shifts are more popular, which meant fairness could be an issue.

A negative impact on a personal level included having to be flexible with the working hours that are worked. One respondent stated that they felt they were always having to ‘play catch-up’. One respondent stated that they do not want to work late every day, and another respondent reported a loss of motivation after a busy week.

Nearly a quarter of respondents (n=7) felt there was a lack of continuity with flexible working and being absent also has a negative impact on the team and patients. Six respondents stated that the reduced number of staff at times meant an increased workload on other members of staff. Two of these respondents stated that more members of staff were needed to accommodate this. One respondent said flexible working reduced communication and another felt there was reduced resilience in the team. Three respondents reported that scheduling for rotas and meetings was more difficult, with one of these respondents stating that they are ‘spending way too much time’ accommodating flexible working.

There was only one respondent that stated any negative impact to patients, highlighting that they ‘are not available one day a week’.

The negative impacts of flexible working reported by the survey respondents can directly impede core operational activities:

- Lack of continuity/ being absent: This directly impacts patient care on wards, as different pharmacists covering a service on consecutive days may require time for handovers or catching up on complex cases. One respondent noted that being ‘not available one day a week’ had a negative impact on patients.

- Reduced communication: Reduced communication can slow down interactions with multidisciplinary teams. This could potentially delay urgent clinical decisions or the resolution of medication issues that require prompt discussion with medical or nursing staff on the wards.

- Increased workload on other members of staff due to reduced numbers: Reduced staffing levels at certain times, which is likely exacerbated by some flexible working patterns, increased the workload on those remaining on-site. This strain on remaining staff can impact their ability to perform essential tasks thoroughly, potentially increasing the risk of errors in high-pressure activities like dispensing or clinical checking. It can also reduce the time available for proactive patient care on the wards. Two respondents felt more staff were needed to accommodate flexible working and manage daily and weekend workloads.

- Scheduling challenges for rotas and meetings: Flexible working complicates the necessary logistical planning for a department serving three in-patient sites where significant numbers of staff must attend multiple sites each week.

Departmental-level support

Some 75% of respondents (n=26) completed the question ‘What else can the department do to support work-life balance?’ (Figure 7).

Four respondents stated there was nothing else that was required of the department. Three respondents suggested improving the advertising of the flexible working option to all Bands. Three respondents wanted a review of the late-night requirement. Two respondents stated that the department should be less hierarchical and have a fairer approach to flexible working. Two respondents highlighted the need to improve staffing levels to support the daily and weekend workloads.

There were also suggestions from respondents to provide overtime slots for seniors to support the daily workload, to understand the travel impact on an individual, and to listen and talk to staff.

A comment from a respondent stated that when on a flexible working pattern, they made up their hours if they were sick or had a sick child instead of taking sick leave and parental leave, which does not allow them sufficient time to recover. One respondent requested breastfeeding rooms and support on phased return following parental leave.

Study limitations

This study has several key limitations that affect the interpretation of its findings. Firstly, the analysis is derived from a low pharmacist response rate, with only 36 eligible responses, which represents less than half of the clinical pharmacists in post in the department. Furthermore, there were very few respondents at a Band 6 level, meaning the findings may not fully capture the views and experiences of pharmacists at this grade.

Secondly, while the survey captures awareness of the Trust’s general flexible working policy, it did not specifically assess awareness or perception of a recent amendment of this policy allowing more flexibility, including hybrid working. Therefore, the finding that 51% of respondents were aware of the policy refers to the general policy, not necessarily the specific new options recently introduced.

Flexible working in context

The growing adoption of flexible work practices in various sectors, including healthcare, is an increasingly important area of study. Flexible work options, such as hybrid working, flex time and telecommuting, are not only reshaping work-life balance but also influencing employee productivity, organisational commitment and turnover intention. Several studies have explored these dimensions, offering insights into the effectiveness of flexible working in different contexts.

In the UK, a 2023 Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development (CIPD) survey revealed that a significant portion of organisations (65%) already offer hybrid or flexible working options.1 This trend has seen a notable increase from 56% in 2022, with 66% of employers recognising the importance of offering flexible working options in job advertisements, according to the CIPD.

This data also aligns with findings from Prescott et al, which reported that more than half of respondents from pharmacy faculties in the United States indicated that working remotely improved their work-life balance.2 This highlights the positive impact of remote work on personal wellbeing, which is essential for job satisfaction and retention.

However, the relationship between flexible work practices and employee retention is complex. Tsen et al demonstrated that job independence moderates the effect of flexible working practices on turnover intention.3 Specifically, employees with greater autonomy in their roles are less likely to leave when offered flexible work options. In contrast, those in interdependent roles, particularly when working from home, showed a higher tendency to leave. This suggests that while flexible working can help retain talent, they must be paired with job roles that allow for autonomy in order to be most effective.

Onken-Menke et al conducted a meta-analysis encompassing 68 studies,4 which found that flexible work schedules, such as sabbaticals and telecommuting, positively impact organisational commitment and reduce turnover intention. They argued that these effects are partially mediated by perceived autonomy, which enhances organisational support.

This aligns with earlier research by Grzywacz et al, who found that flex time, particularly in formal arrangements, was linked to lower stress and burnout levels.5 Their study also noted gender differences and the influence of an employee’s partner’s employment status on the perceived benefits of flexible arrangements.

Flexible working arrangements in healthcare

The findings from the EKHUFT survey align with broader literature highlighting that the healthcare sector presents unique challenges for flexible working due to the requirements for patient interaction and the immediacy of tasks, often necessitating an in-person presence.

According to Mercer et al, healthcare managers often face barriers related to patient interaction and the immediacy of tasks.6 These challenges may limit the effectiveness of flexible working in healthcare settings, where the demands of patient care often necessitate in-person presence.

A study by McCollough further emphasised that neither the formality nor the type of flexible working had a significant impact on job performance in healthcare employees.7 These findings suggest that while flexible work options are beneficial for some sectors, healthcare workers may require more individualised approaches to work flexibility that consider the nature of their tasks.

Poh et al found that flex time is the most preferred and feasible work arrangement in healthcare.8 Their study at Miri Hospital in Malaysia showed that almost half of respondents agreed that flexible working practices improved work-life balance and social distancing during the Covid-19 pandemic, highlighting the increasing importance of such arrangements in maintaining public health and safety.

However, despite the positive perceptions of flexible working, the study also highlighted the need for readiness and preparedness for implementation, as a significant proportion of respondents were still unsure about their organisation’s readiness to adopt flexible work options.

Flexible working recommendations for EKHUFT and beyond

It’s important to note that the results of this EKHUFT survey suggest not everyone requires flexible working. Despite only 43% of respondents being on a flexible working arrangement, 71% of all who responded said they were happy with their working patterns. There were, however, comments from respondents that flexible working needed to be less hierarchical and fairer.

Flexible working is part of the EKHUFT line manager’s handbook, so training will be organised for managers to better understand the policy. There may be a need to explain to flexible working applicants that there are individual circumstances that need to be considered when requests are made, as per Trust policy.

There is a need to increase the awareness of the flexible working policy across the department’s workforce, and this can be done at induction, at regular team meetings and at the beginning of each rotation.

There is also a need to review late nights and weekends, which was already planned. Part of the late-night review would be to consider whether the late nights can be part of pharmacists’ rostered hours.

Other recommendations were to have parental (maternity and paternity) leave training, including discussions around flexible working. The department now has a dedicated member of staff to support staff returning from parental leave.

It has also been identified from this survey that staff who self-roster tend to accommodate any sickness and dependent sickness around their working hours. To recognise that it is important to take time to recover, guidance is recommended on how to manage this in the department to support the health and wellbeing of staff on flexible working patterns.

Research by Pagnan et al9 and Moen et al10 demonstrated that work-life balance is intricately linked to employee health behaviours. The former found that work-family fit positively influenced health promoting behaviours, such as physical activity and family meals, particularly among parents. The latter showed that initiatives like the Results Only Work Environment, or ROWE, improved employee health by increasing schedule control and reducing work-family conflict. These studies underline the broader implications of flexible working practices, not just for job satisfaction but also for long-term employee wellbeing.

Conclusion

While flexible working arrangements in hospital pharmacy offer significant potential benefits for both staff and the department in addressing challenges like recruitment and retention, their implementation requires careful consideration. The EKHUFT survey highlights specific operational challenges within this sector, such as maintaining continuity, managing workload distribution and facilitating communication between pharmacists and the multidisciplinary team, which are particularly relevant given the inherent need for in-person presence in many pharmacy tasks and patient interactions.

Maximising the positive impact of flexible working in hospital pharmacy involves not only offering flexible options but also actively addressing the operational complexities and staff concerns identified and ensuring policies are well understood, applied fairly and supported by adequate staffing levels and management training. The survey results underscore the need for ongoing dialogue and adaptation to effectively balance the benefits of flexibility with the essential service requirements of hospital pharmacy.

Recent NHS Staff Survey results published April 2025 showed year-on-year improvement for EKHUFT in the ‘we work flexibly’ section, although the results from the ‘work-life balance’ questions suggest there are still improvements required.

The key to maximising potential lies in designing flexible working options that cater to the autonomy and job characteristics of employees. Future research should explore how organisations can tailor flexible working to specific job functions, particularly in sectors like pharmacy and healthcare, where in-person requirements for pharmacists often conflict with the benefits of remote work.

Authors

Alice Lo

Medicines value team lead pharmacist, East Kent Hospitals University NHS Foundation Trust

Rebecca Morgan

Lead clinical services pharmacist, East Kent Hospitals University NHS Foundation Trust

Literature review by:

Zainita Meherally

Research assistant medicines information, East Kent Hospital University NHS Foundation Trust

References

1 CIPD. Flexible and hybrid working practices in 2023: Employer and employee perspectives. May 2023. [Accessed June 2025].

2 Prescott WA et al. Remote Work in Pharmacy Academia and Implications for the New Normal. Am J Pharm Educ. 2022;86(10):ajpe8950.

3 Tsen MK et al. Effect of flexible work arrangements on turnover intention: does job independence matter? Int J Sociol 2021;51(6):451–72.

4 Onken-Menke G, Nüesch S, Kröll C. Are you attracted? Do you remain? Meta-analytic evidence on flexible work practices. Business Research 2018;11:239–77.

5 Grzywacz JG, Carlson DS, Shulkin S. Schedule flexibility and stress: Linking formal flexible arrangements and perceived flexibility to employee health. Community Work Fam 2008;11(2):199–214.

6 Mercer D, Russell E, Arnold K. Flexible working arrangements in healthcare. A comparison between managers of shift workers and 9-to-5 employees. J Nurs Administration 2014;44(7/8):411–16.

7 McCollough J. The effects of various forms of flexible work practices on the performance of personnel in healthcare organizations. 2023 Doctoral dissertation, Northcentral University, USA.

8 Poh TE et al. Implementation of Flexible Work Arrangement among Healthcare Workers in Miri Hospital-Assessment of the Validity and Reliability of Flexible Work Arrangement Perceived Benefits and Barriers Scale, and the Exploratory Study. Malays J Med Sci 2022;29(6):89–103.

9 Pagnan CE, Seidel A, MacDermid Wadsworth S. I Just Can’t Fit It in! Implications of the Fit Between Work and Family on Health-Promoting Behaviors. J Fam Issues 2016; 38(11):1577–603.

10 Moen P et al. Changing work, changing health: can real work-time flexibility promote health behaviors and well-being?. J Health Soc Behav 2011;52(4):404–29.