Francis Mégraud

MD

Professor

Laboratoire de Bactériologie

Hôpital Pellegrin

Bordeaux, France

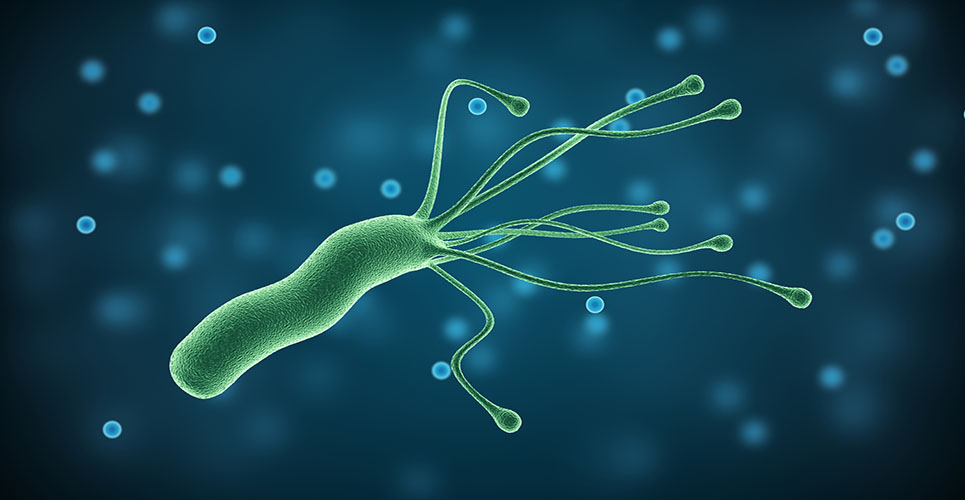

Until the 1980s, the stomach was reputed to be a sterile organ. It was thought that no bacteria could live in such a hostile environment, mainly due to the very high acidity. Although several theories had been proposed to explain the occurrence of peptic ulcers, including psychosomatic disturbances, the most accepted theory was hyperproduction of acid, which led to the development of antisecretory drugs. However, these drugs were unable to stop peptic ulcer disease, which continued inexorably to relapse. In addition, it was noted that this disease always occurred on inflamed mucosa.

The discovery in 1982 of a particular bacterium, namely Helicobacter pylori, as the cause of this inflammation was followed by a number of studies proving that peptic ulcer disease was an infectious disease.

Two kinds of cancer occur in the stomach: gastric carcinoma, which develops from the epithelial cells; and gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma, which develops from lymphocytes. It has been hypothesised that these cancers could result from H. pylori infection, and there is proof that this is the case for gastric MALT lymphoma.

Indications for prescribing H. pylori eradication treatment

The first and most widely accepted indication is for peptic ulcers, in the stomach and the duodenum, even though their pathophysiologies are different (see Table 1).(1) The criteria for causality, developed by Bradford Hill in the 1960s and successfully applied to prove that smoking causes lung cancer, have been applied. There is a strong and consistent association between peptic ulcer and H. pylori infection, and it has been shown that H. pylori infection is present before the ulcer occurs (temporal relationship). The eradication of H. pylori can cure the disease. The epidemiological data reviewed with respect to time and space are consistent with this theory.

[[HPE01_table1_64]]

H. pylori eradication has several other beneficial effects: the ulcer crater heals more quickly, the gastric physiology returns to normal (ie, the highest gastrin-stimulated output returns to normal) and the gastritis lesions are healed, even though it may take years before the mucosa is completely back to normal.

The eradication of H. pylori in peptic ulcer disease has been recommended by all of the consensus conferences around the world.(2) Therapy must be preceded by gastroscopy to observe the ulcer, and also after performing a diagnostic test for H. pylori, as a certain proportion of ulcers can be due to other causes, especially non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug consumption. Peptic ulcer disease may also occur in up to 5% of H. pylori-infected subjects as a result of genetic or environmental factors.

The second highly recommended indication for H. pylori eradication is gastric MALT lymphoma; this is a rare disease (0.1% of H. pylori-infected subjects). The criteria of causality described for peptic ulcer can also be applied to this disease. There is a strong and consistent association: the H. pylori infection precedes the occurrence of the MALT lymphoma, and the eradication of H. pylori cures the disease. Indeed, it is the first example of a cancer that can be cured by antibiotic treatment. However, this is only really true for low-grade lymphomas and where H. pylori involvement is superficial.

Indications for eradication still under debate

It seems logical to think that in the case of dyspepsia the presence of H. pylori infection and the inflammation generated could be the cause of the symptoms present. However, this is not always the case. A meta-analysis of studies testing whether symptoms had been cured one year after eradication has shown that only 10% of patients had relief.(3) Such poor results explain the current debate.

Furthermore, it is not clear whether H. pylori infection should be cured before taking NSAIDs or whether it is harmful to eradicate H. pylori in the case of gastro-oesophageal reflux (data has accumulated to show that in most cases this is not a problem).

Recommended treatment

The best option for treatment of H. pylori is triple therapy, comprising two antibiotics and an antisecretory drug. Antisecretory drugs, especially proton pump inhibitors, despite their effect on pain relief, lead to an increase in the stomach’s pH which favours the action of antibiotics. One antibiotic is not sufficient. Two antibiotics have an additive effect and a better cure rate, and the chance of encountering resistant variants is lower. The compounds that can be used are shown in Table 2.

[[HPE01_table2_65]]

Debate centres around the duration of treatment: originally seven days was recommended. This is still the rule in Europe, although it seems that a longer treatment (10 days) leads to better results (as used in the USA).

Part of the management involves verifying H. pylori eradication by performing a test 4–6 weeks after the end of the treatment. For this purpose, a non-invasive test is used – the (13)C urea breath test.

Clinical trials performed with these drug combinations have led to a high cure rate. However, this success is not confirmed in all areas. The main reason for this is the selection of resistance, especially to clarithromycin. In France, for example, a large survey in clinical practice involving more than 1,200 cases indicated an eradication rate of 70% only. The survey of clarithromycin resistance in France shows that it has now reached 18%. When a strain is resistant to this antibiotic, the chance of success when using it in a combination therapy is very low. Furthermore, after failure, two-thirds of the strains become resistant.

The challenge of the coming years is to find new antibiotics to treat H. pylori infection. However, there is nothing currently in the pipeline. There may be some hope from the genomics approach but this will take time, and the possibility of a vaccine remains a dream. Therefore careful use of antibiotics must be reinforced.

Conclusion

The discovery of H. pylori was a breakthrough in the field of gastroenterology. An important number of stomach diseases can now be considered infectious diseases and be treated with antibiotics. H. pylori is the first bacterium involved in the development of cancers in humans. However, all positive consequences of these findings could be jeopardised by antibiotic resistance, therefore prescribing treatment properly is mandatory.

References

- Current European concepts in the management of Helicobacter pylori infection. The Maastricht Consensus Report. Gut 1997;41:8-13.

- Lee JM, O’Morain C. Who should be treated for Helicobacter pylori infection? A review of consensus conferences and guidelines. Gastroenterology 1997;113:S99-106.

- Moayyedi P, Feltbower R, Crocombe W, et al, on behalf of the Leeds Help Study Group. The effectiveness of omeprazole, clarithromycin and tinidazole in eradicating Helicobacter pylori in a community screen and treat programme. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2000;14:719-28.

Resource

European Helicobacter pylori Study Group

W:www.helicobacter.org

Forthcoming events

5–8 Sept 2001

XIVth International Workshop

Gastroduoenal Pathology and Helicobacter pylori

Strasbourg, France

W:www.helicobacter.org

11–14 Sept 2002

XVth International Workshop Gastroduoenal Pathology and Helicobacter pylori

Athens, Greece

W:www.helicobacter.org